- BY Iain Halliday

What is an offence causing “serious harm”?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

This deceptively simple question was the subject of the Court of Appeal’s decision in the three joined cases reported as Mahmood v Upper Tribunal (Immigration & Asylum Chamber) & Ors [2020] EWCA Civ 717.

Sending a picture of your penis to a 15-year-old girl and causing her to send an “intimate” picture in return does qualify as serious harm. As does a road rage assault with an unidentified “quite long” and “blunt edged” weapon, causing two cuts to the scalp, four superficial cuts to the back, and bruises and grazes on the cheek. Possessing a fake ID and making a “bogus” asylum claim does not qualify. These three facts, together with some guidance of more general application, are what we learn from the decision in Mahmood.

Why does it matter whether an offence has caused serious harm?

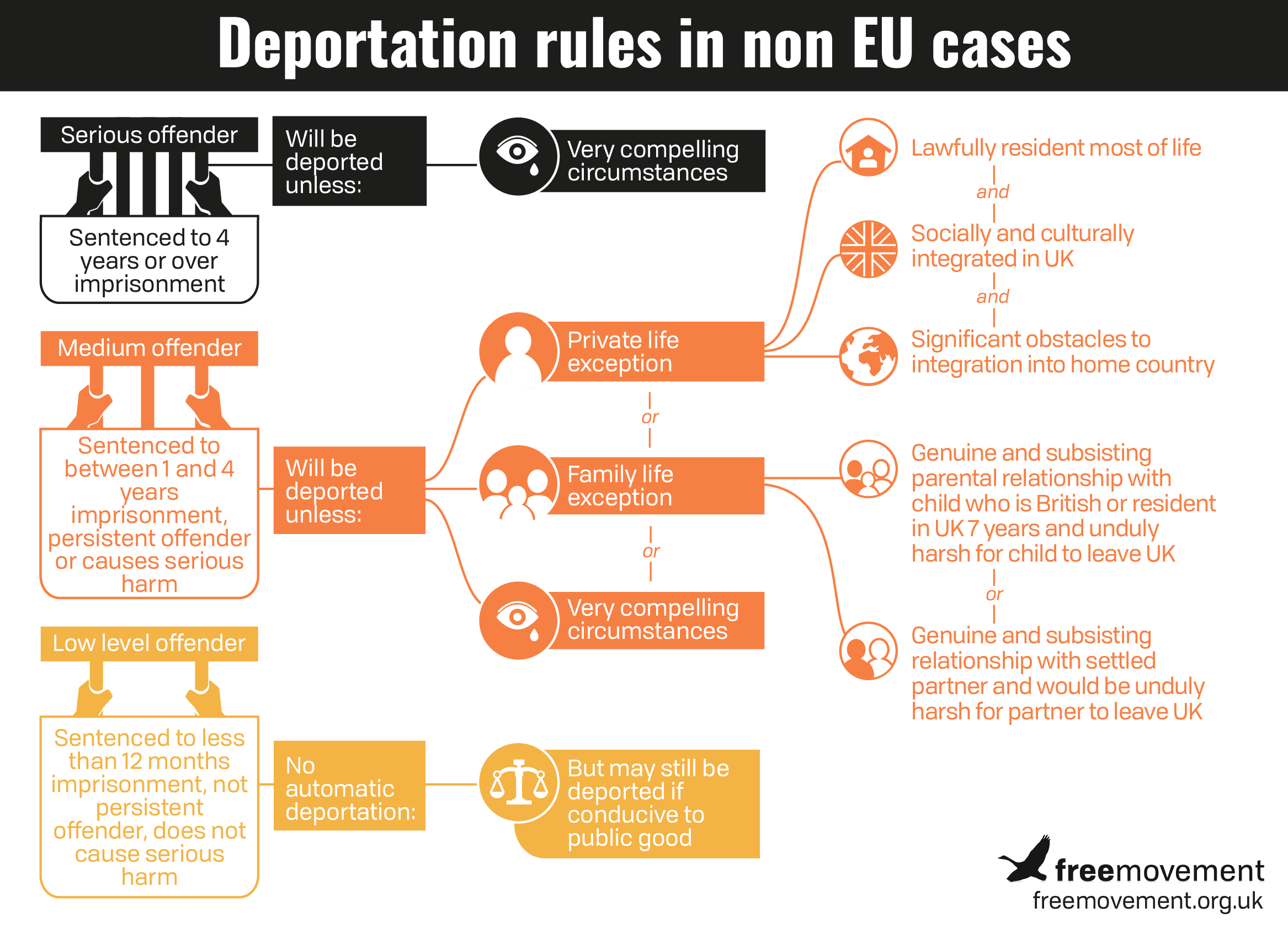

It matters because someone who is not a British citizen, who has been convicted of an offence that has caused serious harm, is a “foreign criminal” as defined in section 117D(2)(c)(ii) of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 and can be deported. (See Nick’s post here for a general overview of the law in this area; Free Movement members can access a whole course.)

There are two other ways to obtain the unflattering designation of foreign criminal. The first is being sentenced to a period of imprisonment of at least 12 months. This is the most common one in my experience, and certainly the most straightforward. All three offences in Mahmood attracted custodial sentences of under 12 months. The second is being a “persistent offender“.

Why so serious?

So what does “serious” mean?

As noted by the court, the three categories of foreign criminal have potential to overlap:

Plainly an offender who has received a sentence of more than 12 months may have done so because he committed an offence which caused serious harm. Equally, an offender who persistently offends is likely to receive a longer sentence (and more than 12 months) because of a poor antecedent history. (paragraph 35)

Given this overlap, the three categories must be read together. The “serious harm” category will only be relevant where the custodial sentence is under 12 months.

This throws light on what may be encompassed by an offence which causes serious harm. While it is possible to think of offences which, despite causing the most serious harm, would not typically attract an immediate prison sentence of at least 12 months (causing death by careless driving is an example), in general paragraph (c)(ii) is not concerned with the most serious kind of harm which comes before the Crown Court. (para 36)

So we are looking for something that is not so grave as to attract a 12 month prison sentence, but still severe enough to deserve the description “serious”. A seemingly simple question becomes a little more complex.

The court rejected the argument that the definition of “serious harm” in the sentencing provisions of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 should be used, endorsing the view expressed in LT (Kosovo) and DC (Jamaica) v. Secretary of State for the Home Department [2016] EWCA Civ 1246.

Causing harm

Then there’s causing “harm”. To whom? A specific victim? Or society in general? Mr Mahmood argued that the harm must be physical or psychological harm to an identifiable individual that is identifiable and quantifiable. The court disagreed:

We see no good reason for interpreting the provision in this way. The criminal law is designed to prevent harm that may include psychological, emotional or economic harm. Nor is there good reason to suppose a statutory intent to limit the harm to an individual. Some crimes, for example, supplying class A drugs, money laundering, possession of firearms, cybercrimes, perjury and perverting the course of public justice may cause societal harm. In most cases the nature of the harm will be apparent from the nature of the offence itself, the sentencing remarks or from victim statements. (para 41)

The potential to harm, or an intention to do harm, is not sufficient. So a conviction for an attempt offence will not qualify (unless serious enough to attract a custodial sentence of over 12 months).

In relation to causation, the harm must be caused by the particular offence. The prevalence of certain offending may cause serious harm to society, but if the individual offence considered in isolation did not cause serious harm, then the offence does not qualify. The court uses the following example:

Shoplifting, for example, may be a significant social problem, causing serious economic harm and distress to the owner of a modest corner shop; and a thief who steals a single item of low value may contribute to that harm, but it cannot realistically be said that such a thief caused serious harm himself, either to the owner or to society in general. (para 39)

This may cause a problem for the Home Office when seeking to rely on the societal harm in drugs cases. The Court of Appeal is clear that supplying class A drugs causes serious harm “on the basis of societal harm caused by the distribution and consumption of drugs”. But where there is only possession or intent to supply, the position is less clear.

Burden of proof

The burden is on the Home Office to prove serious harm on the balance of probabilities. This does not require new evidence from the victim about the harm suffered. The sentencing remarks of the criminal court and the victim statement produced in the criminal proceedings (if such a statement exists) will do. The view of the Home Office in the refusal letter is the starting point, but is not to be afforded any particular weight. Ultimately it is a matter for the tribunal to decide.

Conclusion

All three appeals against deportation were dismissed. Although possessing false identity documents and making a “bogus” asylum was not an offence causing serious harm, the man in question was a persistent offender (“six separate criminal offences committed over a period of 14 years”). The appeal in his case was dismissed for that alternative reason.

Nothing ground-breaking, but a useful judgment which sheds some light on who is, and who is not, a foreign criminal.

SHARE