- BY CJ McKinney

Windrush review calls for root and branch reform at the Home Office

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

What caused the Windrush scandal? According to an independent review by Wendy Williams, published today, the answer lies in increasingly harsh immigration and nationality legislation over the past 60 years. These laws — including those dedicated to the hostile environment — created a situation where long-term residents were required to prove their right to be in UK and were unable to do so.

The Home Office, which should have been looking out for these people, comprehensively failed to do so. The department was hampered by a “culture of disbelief and carelessness” and ingrained “ignorance and thoughtlessness” partly consistent with institutional racism.

Ms Williams, a former solicitor who is now a senior police inspector, says that “policy makers and operational staff lost sight of people the department had a duty to protect”. There was a “lack of empathy for individuals and some instances of the use of dehumanising jargon and clichés”.

The review makes 30 recommendations, which Ms Williams says can be boiled down to three themes:

the Home Office must acknowledge the wrong which has been done; it must open itself up to greater external scrutiny; and it must change its culture to recognise that migration and wider Home Office policy is about people and, whatever its objective, should be rooted in humanity.

The 276-page report is divided into four parts. The first focuses on what happened and to whom — all the hidden suffering eventually forced onto the political agenda by the dogged reporting of the Guardian’s Amelia Gentleman.

The report notes that hundreds, if not thousands, of people were “essentially denied their rights”. Some lost jobs, some were denied healthcare or benefits, others deprived of their liberty and even removed from the UK. Ms Williams sprinkles the report with case studies — such as that of Pauline, who arrived in the UK in 1961 aged 12.

When Pauline went on a two week holiday to Jamaica with her daughter in 2005, she was denied re-entry, detained, slipped into a diabetic coma and nearly died. She lost her job and only managed to get back to the UK in 2007, with the help of an immigration lawyer.

Part 2 traces the “complex interplay of historical, social, political, and organisational factors that contributed to the scandal”. It says that there is no evidence that the Windrush generation were deliberately targeted because they were black. Rather, they were “a generation whose history was institutionally forgotten” when policies affecting their interests were drawn up.

“The department was aware of significant concerns about the potential for the hostile environment measures, and specifically the Right to Rent scheme, to result in discrimination. It was even aware that the data used to conduct its own proactive checks were flawed… Despite the warnings, the department failed to monitor, or properly evaluate, the effectiveness and impact of the compliant environment measures. The department accepts that voluntary returns, originally seen as an indicator that the measures were working, had been declining at a significant rate (as at March 2018). There is therefore little evidence to support an assessment of the effectiveness of the compliant environment measures, and whether they are achieving the policy aims”.

Page 140

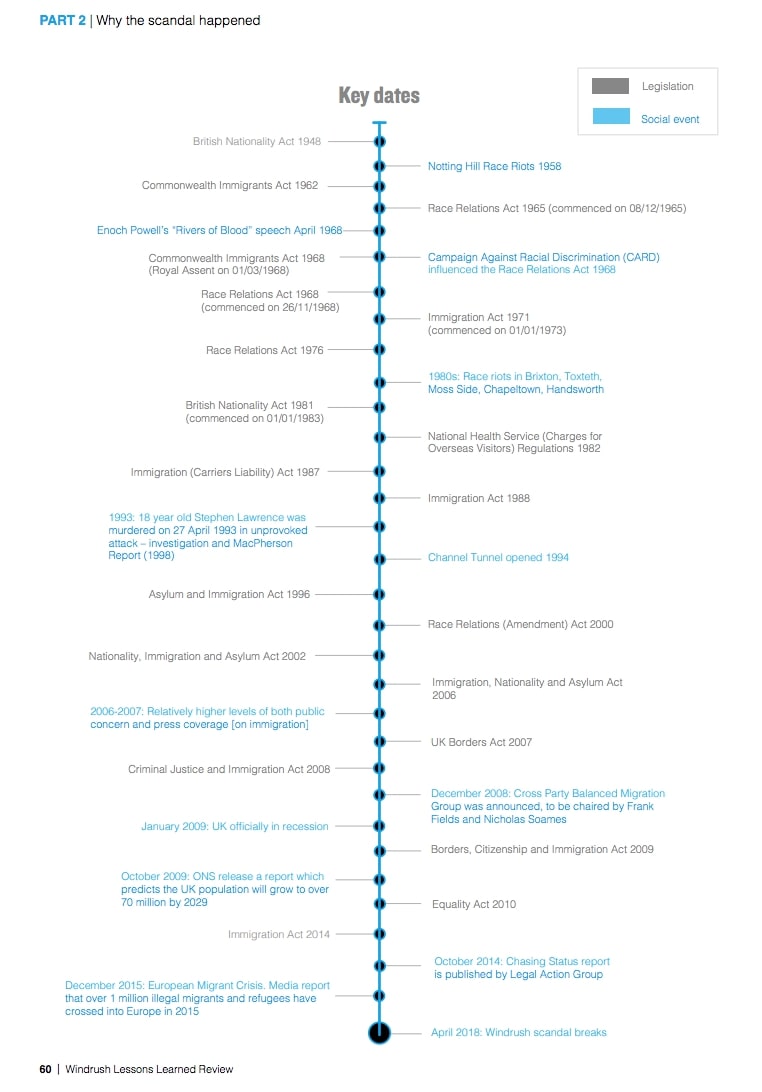

The report traces the development of restrictive immigration laws and policies, starting with the “sea-change” of the Commonwealth Immigration Act 1962. Culminating in the hostile environment measures of in-country status checking in the 2000s, these “effectively set the trap” for the Windrush generation.

The Home Office was ill-equipped to disarm the trap. The report criticises the department sorely lacking in institutional memory for “a failure to see how past legislation combined with evolving policy and to assess what impact this might have on vulnerable people and minorities, especially the Windrush generation, alongside a focus on meeting targets”. The amount of residence evidence demanded of people seeking documents to prove their right to be here was “unreasonable” and “clearly excessive”.

[application]There is also a word for the unfathomable complexity of UK immigration law as a contributing factor: “even the department’s experts struggled to understand the implications of successive changes in the legislation”.

The third part of the report focuses on the various ways in which the department has tried to make amends once Windrush became politically untenable. These include a taskforce that has helped thousands of people sort out their status, and a compensation scheme. Internally, there have been various reforms such as a Chief Casework Unit aiming to improve decision-making, and a “safety value mechanism” within Immigration Enforcement.

Overall, Ms Williams says, these measures “address some of the issues which led to the crisis. However, they do not sufficiently address the fundamental problems that exist”.

Finally, there is a section on findings and recommendations. The Home Office must accept that “a systemic and cultural change is necessary”. Success would be a department that has:

looked beyond trying to explain Windrush as an unlucky series of mistakes, but instead recognises it as an historical series of events deeply embedded in current and past structures, policies and cultures.

Some of Ms Williams’ 30 recommendations are aimed at changing the department’s culture. Staff should, among other things, be made to “learn about the history of the UK and its relationship with the rest of the world, including Britain’s colonial history, the history of inward and outward migration and the history of black Britons”.

Other recommendations include:

- An unqualified and sincere apology

- A full review of the hostile environment

- A Migrants’ Commissioner “responsible for speaking up for migrants”

- Giving more powers to the immigration inspector

- A new Home Office mission statement based on “fairness, humanity, openness, diversity and inclusion”

- An urgent review of complaints procedures, including an independent complains examiner

- An “overarching strategic race advisory board”

- Training of various kinds for staff at all levels

You can read Colin’s submission to the review here.