- BY Colin Yeo

Why do the “migrants” in Calais want to come to the UK?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

“Cockroaches” according to Katie Hopkins. A “swarm” according to our likeminded Prime Minister, David Cameron, and The Daily Mail (again). An “army” according to the popular press, who seem to think we should literally send troops into France (without asking the French, we can assume) to hold the thin red line. “Migrants” to others. Why never “refugees”, though, which is what most of them are? What do we know about who these people are — brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers and children, all of them — and why they want to come to the UK?

“Cockroaches” according to Katie Hopkins. A “swarm” according to our likeminded Prime Minister, David Cameron, and The Daily Mail (again). An “army” according to the popular press, who seem to think we should literally send troops into France (without asking the French, we can assume) to hold the thin red line. “Migrants” to others. Why never “refugees”, though, which is what most of them are? What do we know about who these people are — brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers and children, all of them — and why they want to come to the UK?

Back in 2002, at the height of the previous Calais hysteria, the Home Office commissioned some respected researchers to ask some of people themselves. Their answers are still the best information we have. Some of the nationalities have changed but the motivations are probably perennial.

But first, some numbers and some perspective.

The Immigration Minister, James Brokenshire, reported on 21 July 2015 that there are thought to be about 3,000 people in the Calais areas trying to reach the United Kingdom. To put that in perspective, the old Sangatte camp used to house around 2,000 when it was closed in 2002; the present numbers, unlike the hype, aren’t that much higher.

The year 2002 was the year that asylum claims in the UK hit their peak of 84,132. The numbers have fallen considerably since then and the official statistics record that the number of claims in the year ending was a mere 25,020. There was a slight increase in claims last year, but the numbers are clearly still much, much lower than they were.

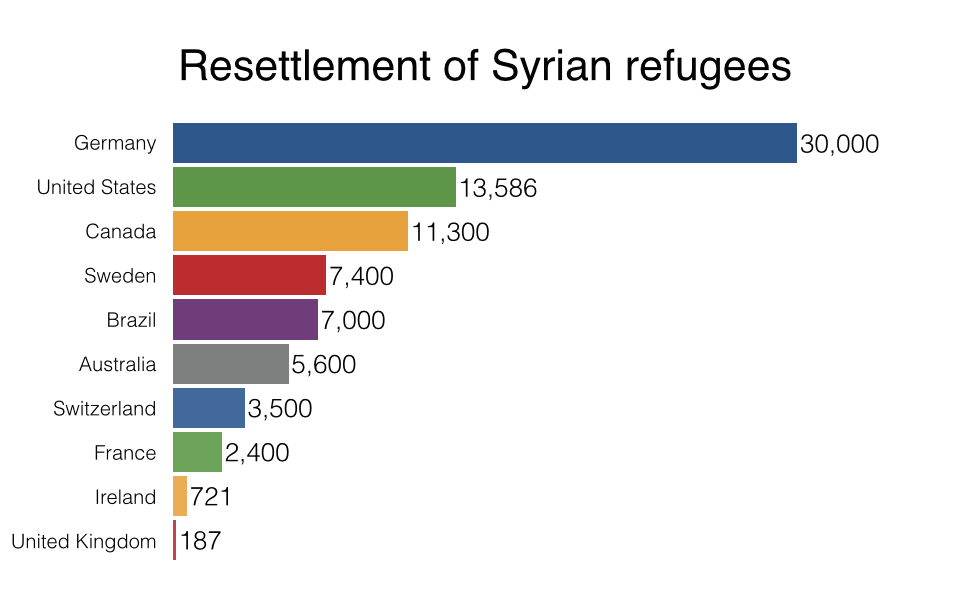

For some broader perspective, the Syrian civil war has generated over 4 million refugees. 1.7 million of them reside in Lebanon, meaning that over 20% of the population of Lebanon is now Syrian refugees. The Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan alone houses over 80,000 Syrian refugees. Only around 4,000 of the 4,000,000 Syrian refugees have reached the UK in the last few years. We did everything in our power to stop those 4,000 from entering our country and we have only voluntarily offered resettlement to a mere 187 Syrian refugees, far fewer than other comparable countries.

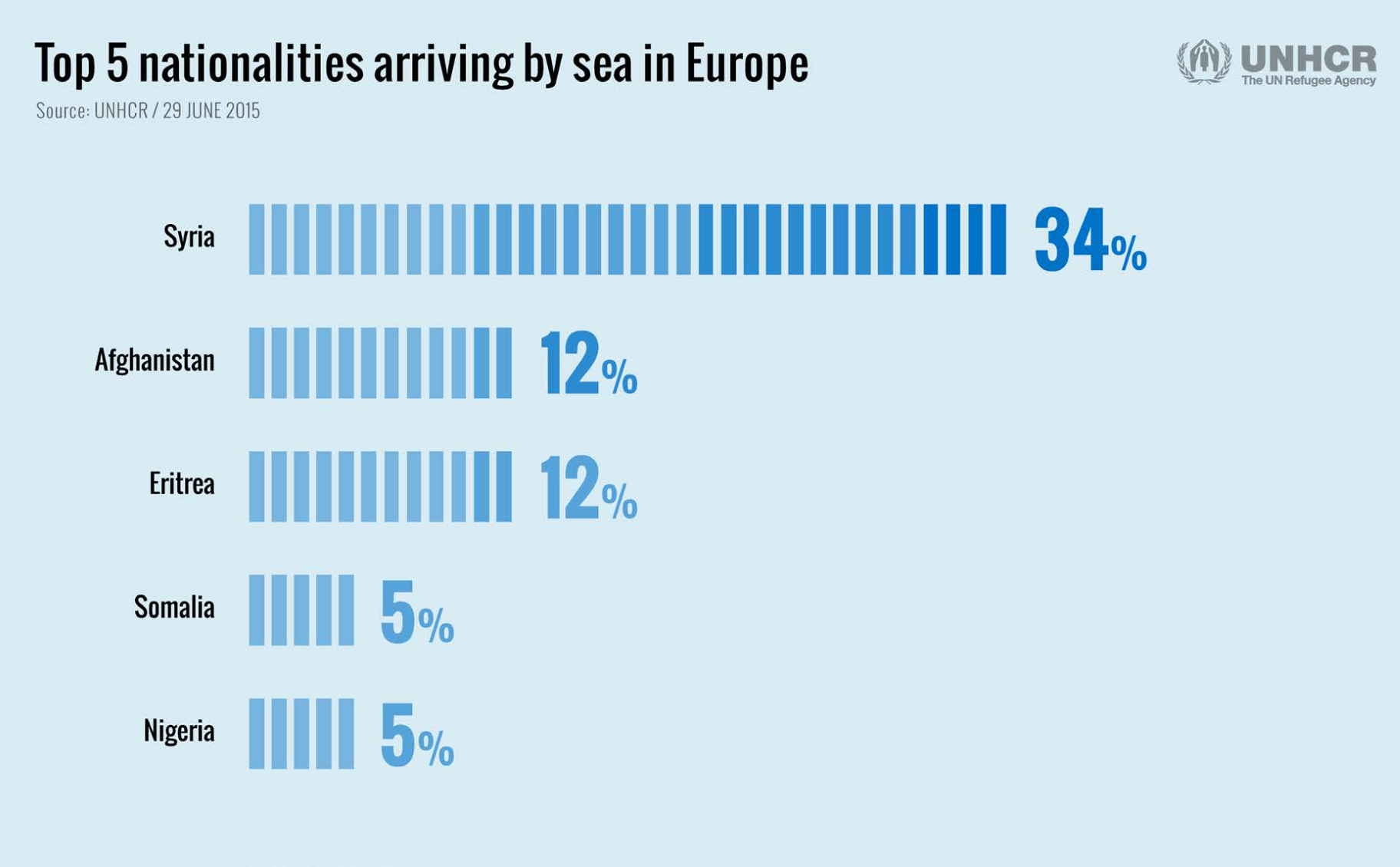

Broken-shire also reported that the top five nationalities of those in Calais are Syrian, Eritrean, Sudanese, Iranian and Iraqi. This is similar to the top five countries of origin of those crossing the Mediterranean, reported by UNHCR to be Syria (34%), Afghanistan (12%), Eritrea (12%), Somalia (5%), Nigeria (5%). The Syrians are self evidently refugees. If we look at the UK grant rate for the other nationalities, the latest official statistics say 85% of Eritreans are granted asylum, 79% of Sudanese and 56% of Iranians.

The vast majority of those at Calais are refugees and would be recognised as such if they managed to reach the UK. But why do they want to come specifically to the UK so much that they will risk the one thing they have left, their lives? Why not stay in France?

The Home Office previously commissioned research on this question and in 2002 the resulting report was published. Understanding the decision-making of asylum seekers was based on 65 interviews with asylum seekers in 63 households, with each interview lasting 80- 120 minutes.

The principal aim of those questioned was to reach a place of safety. The mix of nationalities at Calais suggests that factor remains constant.

Agents were found to play a key role in the final destination:

Some agents simply facilitated travel to a destination chosen by the asylum seeker. Other agents directed asylum seekers to particular countries without giving them any choice. Yet other agents offered asylum seekers a priced ‘menu’ of destinations from which the asylum seeker could then choose.

For those that did have an element of choice about their destination, there were a range of factors that influenced that choice:

These were: whether they had relatives or friends here; their belief that the UK is a safe, tolerant and democratic country; previous links between their own country and the UK including colonialism; and their ability to speak English or desire to learn it.

There was very little evidence that the sample respondents had a detailed knowledge of: UK immigration or asylum procedures; entitlements to benefits in the UK; or the availability of work in the UK. There was even less evidence that the respondents had a comparative knowledge of how these phenomena varied between different European countries. Most of the respondents wished to work and support themselves during the determination of their asylum claim rather than be dependent on the state.

Attitudes towards work for those questioned seemed to be complex. Back in 2002 the media and Home Office were obsessed with the idea that bogus asylum seekers wanted to claim benefits. These days, after our collective experience of EU migration, most of us now surely recognise that the desire to work is likely to be a more significant motivation for migration.

The research found that most of those questioned believed they would be allowed to work, wanted to work and thought they would have to work:

Many of the respondents had worked in the country of origin (and acquired skills and had careers there), and wanted to do so again when they arrived in the country where they claimed asylum. Finding a job was important because it enabled people to rebuild their lives after what had often been traumatic and disruptive experiences. It helped refugees to regain their self-respect and confidence, and to focus upon the future…

This being the real world, there is no easy answer to the question “why?” Work, friends, family, language, historical links to the UK and, ironically, the UK’s reputation for fairness, tolerance and welcome all play their role.

SHARE