- BY Iain Halliday

When is a foreign criminal not a foreign criminal?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

That is the question answered by the Upper Tribunal in SC (paras A398 – 339D: ‘foreign criminal’: procedure) Albania [2020] UKUT 187 (IAC).

The appellant was convicted of murder and sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment. So he is, by any reasonable definition, a criminal. He is a citizen of Albania — so clearly foreign.

But he is not, from a legal perspective, a “foreign criminal”. This is because his conviction was in Albania.

Offences outside the UK

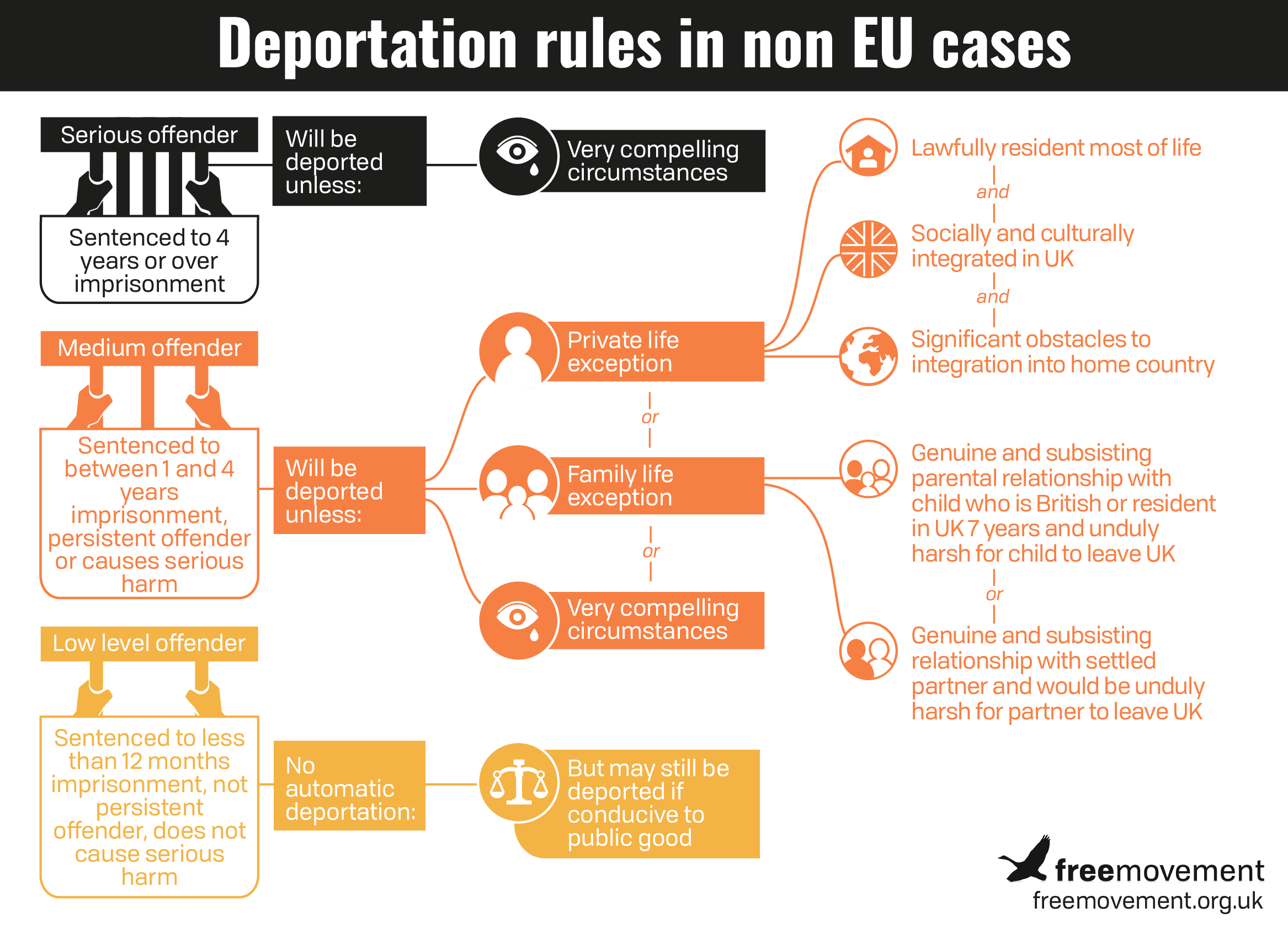

As regular readers of this blog will know, there are strict rules set out in Part 5A of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 for those who seek to resist deportation on the basis of their private and family life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. This regime applies to anyone who is a “foreign criminal”, as defined in section 117D(2).

That definition requires a criminal conviction in the UK. There was no such conviction here — only a murder conviction in Albania. As such, these provisions did not apply.

Paragraphs A398 to 399D of the Immigration Rules also regulate deportation and Article 8. The Upper Tribunal had previously flip flopped on whether the use of the phrase “foreign criminal” in the Rules has the same meaning as in section 117D(2).

This conflict has now been resolved in favour of using the same definition:

…there is, we find, no escaping the conclusion that paragraph A398 governs each of the Rules that follows; and that its use of precisely the same expression – “foreign criminal” – as is found defined in section 117D of the 2002 Act inexorably means that the expression is to be construed in accordance with that statutory definition and does not carry the wider meaning described by Upper Tribunal Judge Coker [in Andell (foreign criminal – para 398) [2018] UKUT 198].

So the Immigration Rules don’t apply either. What, then, is the relevant test that someone in this position must satisfy to defeat deportation?

Unjustifiably harsh consequences

The tribunal required the appellant to show “unjustifiably harsh consequences” for him, his wife, and/or children. Where does this test come from I hear you ask? Answer: the entry clearance rules.

These, the Upper Tribunal decided, ought to be used to “guide the assessment of public interest in the appellant’s removal by means of deportation” [paragraph 94]. This is because it would be:

…abhorrent for the appellant to gain any advantage over those seeking entry clearance, who have committed similar offences, by reason of the fact that his presence in the United Kingdom arises only because he entered unlawfully. [83]

A period of imprisonment of over four years means that paragraph S-EC.1.4 of the suitability criteria of Appendix FM of the Immigration Rules cannot be met. Unjustifiably harsh consequences therefore need to be shown, as per paragraph GEN.3.2(2).

The tribunal was not satisfied that this test could be met. The severity of the crime, SC’s poor immigration history, his use of a false identity, and the availability of two adult children to help his wife care for the younger children, all led to the conclusion that: “the outcome of the proportionality balancing exercise is… firmly in the favour of the respondent”.

The reliability of the murder conviction

The appellant sought to challenge his conviction in Albania on the basis that he had been tortured whilst in police custody and forced to confess. He claimed that he had acted in self-defence, had no legal representation at the trial, and that there had been a miscarriage of justice. The conviction dated back to 1994. Expert evidence was produced in support of his claim that corruption was common, and criminal proceedings often unfair, in Albania at that time.

This claim was significantly undermined by a record of the court proceedings, which told a very different story. It recorded that the appellant was legally represented by a defence lawyer who advocated on his behalf, that he was convicted after detailed consideration of the facts, and that he was afforded a right of appeal to a superior court.

That record stands in stark contrast to the account which the appellant decided he would put forward, as the latest in a sustained series of attempts, stretching back over a decade, to resist deportation by any means at his disposal… His contention that the document is wholly “fabricated” is the only way in which he can seek to evade the damage done to his case by the emergence of the court record in the present proceedings. [88]

Needless to say, the tribunal preferred the version of events in the record of proceedings to the appellant’s explanation.

Re-visiting a procedural decision

The final issue addressed by the Upper Tribunal is when a procedural decision can be overturned.

An updated expert report, which considered the record of the criminal proceedings in Albania in 1994, was produced on the day of the hearing. The tribunal refused to consider this on the basis that:

…it would send entirely the wrong message to those who come before the Upper Tribunal, whether as appellants or respondents, that directions regarding service count for little or nothing. [39]

Fair enough. It is only fair that the Home Office has time to consider the report and prepare for the hearing.

But the hearing didn’t finish that day, and was adjourned to seven weeks later. That would have allowed the Home Office time to consider the report and make submissions on it.

The appellant’s solicitors asked that the decision to exclude the report be re-visited. The tribunal refused, relying on a decision of the Tax and Chancery Chamber which held that it will be rare and unusual for such decisions to be revisited.

Paragraph A398 of the immigration rules governs each of the rules in Part 14 that follows it. The expression ‘foreign criminal’ in paragraph A398 is to be construed by reference to the definition of that expression in section 117D of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002: OLO and Others (para 398 – ‘foreign criminal’) [2016] UKUT 56 affirmed; Andell (foreign criminal – para 398) [2018] UKUT 198 not followed.

A foreign national who has been convicted outside the United Kingdom of an offence is not, by reason of that conviction, a ‘foreign criminal’ for the purposes of paragraphs A398-399D of the rules.

In the absence of a material change in circumstances or prior misleading of the Tribunal, it will be a very rare case in which the important considerations of finality and proper use of the appeals procedure are displaced in favour of revisiting and varying or revoking an interlocutory order: Gardner-Shaw (UK) Ltd v HMRC [2018] UKUT 419 followed.

SHARE