- BY Colin Yeo

What are ‘short term holding facilities’ like the Manston refugee camp?

Table of Contents

ToggleA new report has been published this morning by HM Chief Inspector of Prisons on the controversial short term holding facility for refugees at Manston in Kent. The inspection took place in late July 2022, before the current Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, is reported to have prevented hotel bookings that would have enabled refugees to be released from the facility. We know that conditions have, as a consequence, considerably deteriorated. A facility designed to hold no more than 1,600 people was apparently crammed with coming up to 4,000 as a consequence. One Afghan family is reported to have been detained for 32 days.

The new report reveals that things were pretty bad back in July. The inspectors found that governance of health care processes was weak, that some children were detained for far too long, governance of security clearances and training of staff was poor, data collection was inconsistent and fragmented, there was a lack of leadership and more. Senior civil servants and ministers have been repeatedly warned over the last two years that there were serious problems at these refugee camps (see below), and yet the situation has been allowed to get even worse.

But what actually is a ‘short term holding facility’? And what are the legal rules that govern their use?

What is a short term holding facility?

A short term holding facility is a place for detaining international passengers for a short time while the immigration authorities decide what to do with them. They are not generally intended for refugees.

A total of 24,004 people entered immigration detention in the year ending June 2022. At any given time, though, there are around 2,000 people in immigration. The vast majority of people who experience detention are detained for only a short period when they first arrive in the United Kingdom. They might be detained for a few hours or overnight while an immigration official questions them or establishes their identity, for example. In normal circumstances, this would be at what is called a ‘short term holding facility’ at the port of arrival or very close to it.

A short term holding facility is defined in section 147 of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 as a place ‘solely for the detention of detained persons for a period of not more than seven days or for such other period as may be prescribed’. No other period has been prescribed: the statutory limit for detention in short term holding facilities is therefore seven days. Detention in such a facility for any longer period of time is unlawful.

Traditionally, a short term holding facility would be thought of as a secure waiting room at Gatwick or Heathrow, for example. A report by Her Majesty’s Insectorate of Prisons found in 2020 that there were 13 short term holding facilities then in use. More have clearly been opened since then because the Manston refugee camp was not listed.

One of two outcomes would normally follow from detention at one of these facilities. A person might be formally and legally admitted to the UK for the purpose for which they originally arrived, for example as a visitor or student. Alternatively, they might be formally refused entry and sent back to the country they came from on the next flight.

Why are short term holding facilities being used for asylum claimants?

If the newly arrived person claims asylum, they are neither given formal permission to stay, oxymoronically called ‘leave to remain’, nor are they removed. Instead, they are given a form of temporary permission to stay called ‘immigration bail’ pending a final outcome to their case. If the asylum claimant needs accommodation, the Home Office will need to provide it. Until the person is released to this asylum accommodation, they might be kept in a short term holding facility.

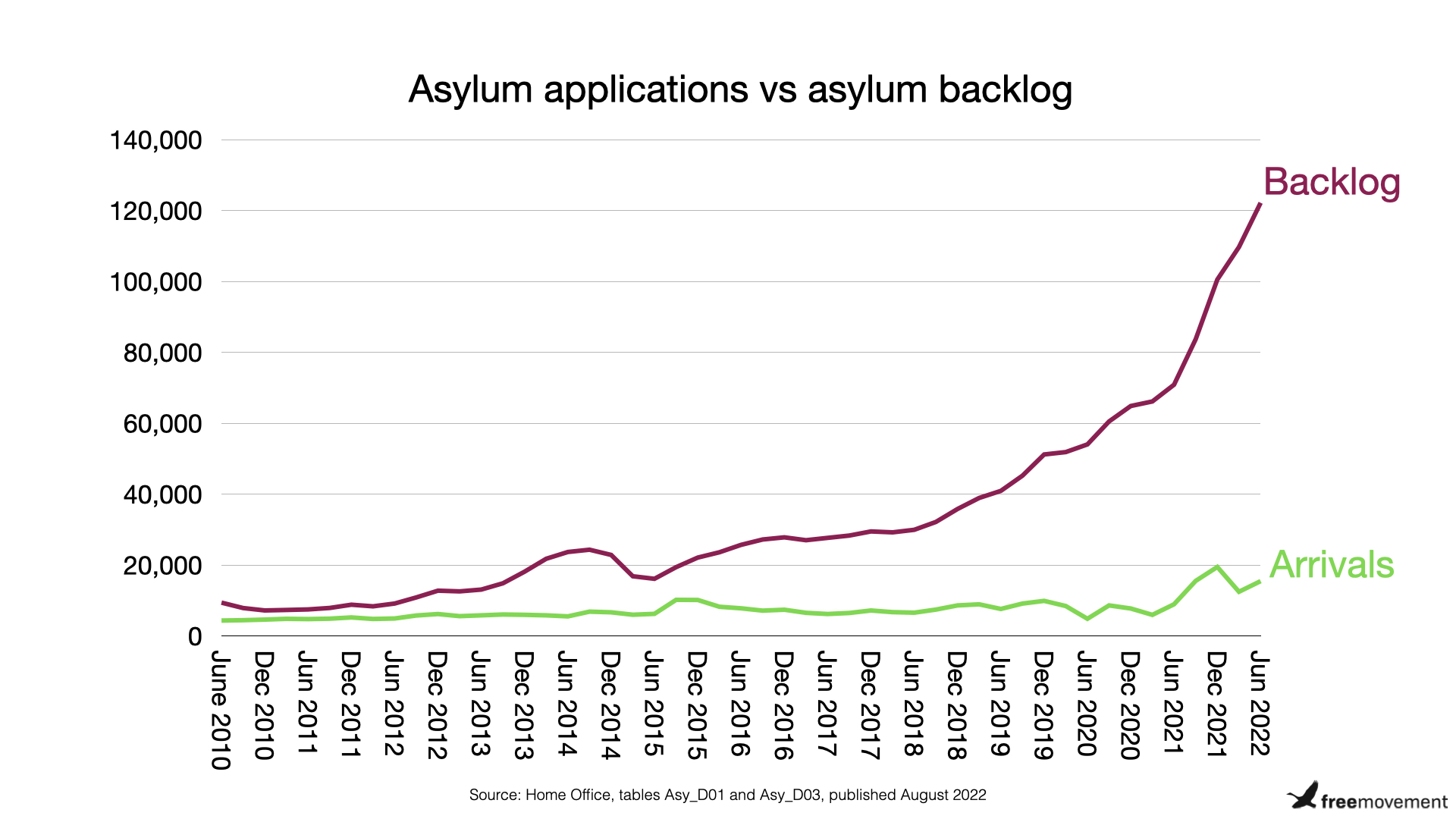

At the moment, all of the normal asylum accommodation is in use because the asylum backlog has been allowed to grow so considerably in the last few years. Hotels are therefore being used instead. It is reported that Suella Braverman refused to authorise release of asylum claimants to hotels (a claim she denies), meaning that the number held in short term holding facilities grew very quickly and very considerably during the first of her short tenures as Home Secretary. What Braverman had expected to happen is unknown; this was very clearly a foreseeable consequence. It was absolutely inevitable, in fact.

What is the law on short term holding facilities?

Any period of detention of any length is a major interference with any person’s liberty and must be authorised by law.

The power to detain any migrant originates in the Immigration Act 1971, as interpreted and to some extent circumscribed by case law like the Hardial Singh case and by any relevant Home Office policies. A short term holding facility is a place of detention, not a power of detention. The normal constraints applying to any immigration detention therefore apply.

The key legal instrument which applies specifically to short term holding facilities is a statutory instrument, the Short-term Holding Facility Rules 2018 SI 2018/409. These rules are made under section 157 of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999. The rules were introduced following the Shaw Review. Previously, the optional power to introduce rules had not been taken up.

Firstly, as far as I can see, there is no official or legal designated list of short term holding facilities. At the whim of the Home Office, any place can become a short term holding facility. Sometimes it might be a room, sometimes a disused lorry container, sometimes a marquee in a car park. Wherever is used as a short term holding facility is a short term holding facility, basically. This is why, when inspectors asked for a list of facilities in 2020, the Home Office was not even able to provide one.

As is always the case with immigration detention, written reasons must be given to that person when they are first detained (rule 12) and their detention must be reviewed after 24 hours (general detention policy p30-31).

The drafting of the rules is unclear. At least, unclear to me. The rules envisage a subclass of short term holding facilities referred to as ‘holding rooms’. Several key rules applying to the general class of short term holding facilities, for example on accommodation, clothing, hygiene and more, are disapplied for this subclass. The problem is that a ‘room’ need not be an actual room as such because the term ‘holding room’ is given a formal definition by the rules: ‘a short-term holding facility where a detained person may be detained for a period of not more than 24 hours unless a longer period is authorised by the Secretary of State.’ This is essentially a circular definition, so it is not clear at all what short term holding facilities are or are not ‘holding rooms’. The intention of the rules seems to be that a holding room is whatever the Home Office decides it is.

The reality — which is only indirectly reflected in the rules themselves — is that there are two classes of short term holding facilities: residential facilities and non-residential facilities. The latter are referred to as ‘holding rooms’.

Rule 6 on these holding rooms (that need not be actual rooms) states that ‘a detained person must not be detained in a holding room for a period of more than 24 hours’. However, this period can one extended by the Secretary of State if he or she ‘determines that exceptional circumstances require it’. So there is normally a limit of 24 hours but it can potentially be extended. While the rules seem to say this must be the Secretary of State, in fact that also means an official acting on behalf of the Secretary of State.

As ever, the Home Office has a policy for that. The policy is imaginatively entitled the ‘Short-term Holding Facility Rules 2018‘. To differentiate it from the rules themselves, I will call this document the short term holding facility policy. The policy sets out the level of seniority of officials who may authorise detention beyond 24 hours in a holding room. An initial decision must be authorised at Senior Officer or Senior Executive Officer level and for a defined period of no more than 12 hours. Detention beyond 36 hours must be authorised at Assistant Director or grade 7 level. Separate rules on authorisation apply to children.

The rules also cover matters such as adequacy of accommodation, clothing, food, hygiene and recreation. These rules apply whenever a person is held in residential facilities but do not apply to holding rooms.

There is also a further relevant document, pointed out to me by Jed Pennington. This is the Immigration (Places of Detention) Direction 2021. It is not a formal statutory instrument but it is made pursuant to several statutory powers. It is, I think, legally binding while in force, although it can easily be changed by the Home Office. Paragraph 4 of that direction, referring back to paragraph 3(c), imposes a limit of five consecutive days on detention at a short term holding facility. This is less than the absolute statutory limit.

Is it lawful to detain thousands of refugees for longer than 24 hours?

As far as I am aware, there is no detention limit of 24 hours applicable to short term holding facilities unless they are specifically holding rooms as (very badly) defined in the rules. For holding rooms, there is a limit of 24 hours, although it can potentially be extended in some very limited circumstances. A review of detention must always in all circumstances for all immigration detainees take place within 24 hours, though, according to Home Office policy. And failure to carry out such a review would render the detention unlawful and meant the person concerned could make a claim for compensation.

The absolute detention limit for all short term holding facilities is seven days. That limit has been voluntarily reduced by the government to five consecutive days. After that, the detainee must be released or transferred to a normal immigration detention centre. If a person is detained in short term holding facilities for longer than five days, they can make a compensation claim for unlawful detention.

Where a person is detained in residential short term holding facilities, the rules set out mandatory minimum standards. For example, the Secretary of State must certify of sleeping accommodation that ‘its size, lighting, heating, ventilation and fittings are adequate for health’ and a maximum number of people who may be accommodated in the room must be specified in the certificate (rule 13). Accommodation separate to the opposite sex must be provided (rule 14) and separate family accommodation is required (rule 15). Clothing ‘adequate for warmth and health’ must be provided (rule 16), as must adequate food and drink (rule 17), hygiene facilities ‘necessary for personal health and cleanliness’, the facility for a daily bath or shower and a daily shave (rule 18), recreation facilities if reasonably practicable (rule 19), open air time (rule 20) and facilities to meet detainees cultural and religious needs (rule 21).

Other requirements include a right receive visits (rules 23 and 25), to send and receive correspondence at their own expense (rule 24), a right to private consultation with a person’s lawyer (rule 27), access to a telephone and to the internet (rules 28 and 29) and access to health care (rule 31).

Even before today’s report, the HMIP inspection report from 2020 found that ‘there has to date been inadequate leadership and management of detention’. The Home Office had forgotten to notify the inspectorate of nine holding facilities and the list of facilities changed several times. Officials were unable to provide information on the numbers of detainees, length of detention and the types of detainees held. A follow up in December 2021 found ‘conditions that were at times completely unsatisfactory, and ongoing weaknesses in Home Office governance and systems of accountability and safeguarding.’

A further report in July 2022 (actually sent to ministers in February 2022), this time by the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, found that the Home Office response to small boats was ‘poor’ and that ‘[d]ata, the lifeblood of decision-making, is inexcusably awful’. David Neal squarely blamed ministers and senior officials. ‘The workforce can do no more, he wrote. ‘They have responded with enormous fortitude and exceptional personal commitment, which is humbling, and they are quite rightly proud of how they have stepped up.’ The key point from Neal’s report is that the Home Office was denying reality by showing a ‘refusal to transition from an emergency response to what has rapidly become steady state, or business as usual’.

Four years after small boat crossings began, the Home Office response continues to be extremely poor. In fact, the response is getting worse, not better. The fundamental underlying problem is the continued failure to tackle the growing and now massive asylum backlog, which means there is no normal asylum accommodation left for refugees to be moved into. The blame for both the cause and symptoms lie at the top of the Home Office, with ministers and senior officials.

SHARE