- BY CJ McKinney

“Westernised” Iraqi family granted asylum

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

What does it mean to be ‘westernised’? It is striking that a term that is used so frequently in this jurisdiction has never been more closely defined. I would suggest that this is because, like obscene material, it is because we ‘know it when we see it’.

Some musing from Upper Tribunal Judge Bruce in the newly reported case of YMKA & Ors (‘westernisation’) Iraq [2022] UKUT 16 (IAC). It concerns an Iraqi family applying for asylum on the basis that their views and lifestyle — rejection of Islam, refusal to wear the hijab, accepting their daugher’s boyfriend Mike — would put them at real risk of serious harm if sent back to Iraq.

The judge commented that ‘westernisation’ seems to amount to:

a fairly loose bundle of characteristics: an adherence to a particular set of values, a rejection of religion, and prominently, the freedom to enjoy a socially liberal way of life… [the family] mix freely with members of the opposite sex; they all accept A4’s relationship with her boyfriend; they go out and socialise without fear of saying the wrong thing; they cherish friendships with individuals of diverse backgrounds; they enjoy an unfettered range of entertainment and culture; the children will grow up free of the expectations placed upon them by Iraqi society, particularly in terms of gender roles and personal choices; the girls make it clear that they do not want to wear conservative Islamic clothing.

Being socially liberal in a hyper-conservative society is not, she found, a reason to grant asylum under the Refugee Convention. But some of the issues bundled into the “westernisation” argument clearly did speak to actual Convention reasons: “no dispute arises that there is a protected right not to believe in a god”, for example.

Similarly, a westernised person might be taken by potential persecutors to have unacceptable political or religious beliefs, and so attract Convention protection that way:

In his evidence A1 [the father] very candidly explained that he might be able to “fake” being Muslim. He has, for instance, seen many Muslims at prayer throughout his life, and so knows the order in which you stand, bow etc. On further probing, however, he admitted that he had no idea what the words are. This highlights a discrete protection issue. Envisage a claim which would prima facie fail on the grounds articulated by Hope LJ in HJ (Iran) and by Laws LJ in Amare: a man who, for instance, had no particular religious or ideological underpinning to his lifestyle, who simply enjoys the freedom that life in the UK can offer. That man could quite reasonably be expected, as a matter of law, to simply conform to the norms and expectations of the society that he is going back to. The Convention is not there to protect him from having to live under a regime where pluralist liberal values are less respected than they are here. The question remains whether it is possible for him to safely do that. If an individual has for instance been living in the UK for a very long time or is unfamiliar with the prevailing culture in his country of origin, there may always be the risk that his modified behaviour will slip, or he will not know how he is supposed to behave. In a particularly hostile environment, such as those discussed in the country guidance cases I mention above, this could expose him to harm. It would then matter little what he himself believed: the necessary nexus is created by the perspective of the persecutor.

Evidence about fashion or lifestyle preferences that at first glance seems irrelevant to an asylum claim must therefore be “carefully assessed” to see whether there are Convention reasons lurking underneath.

In this case, 23-year-old A4 — a “fervent feminist” who “rejects the institution of marriage” — would face a real risk of serious harm in Iraq on account of political beliefs she would be incapable of suppressing.

The judge went on to grant asylum to the rest of the family on the basis of their religious beliefs. In Iraqi society today,

… an individual does not have to sell books, or shout on a street corner, to proclaim that he is not a Muslim: his lack of faith is apparent in his everyday actions. A1 will be regarded with curiosity if he permits his daughters to go out unchaperoned; that curiosity will rise to suspicion if he is never seen at mosque; suspicion would quickly escalate to hostility if the family fail to observe the fasts in Ramadhan or to don black during Muharram; that hostility could, at any time, give rise to persecution if, for instance, the women insist on remaining unveiled or the family’s attitudes lead to them being identified as particularly wealthy. I am satisfied that in these circumstances the members of this ‘westernised’ family do face a real risk of persecution because they are atheists. They do not wish to adhere to conservative Islamic norms because they fundamentally do not agree with them. They should not be expected to do so simply in order to remain safe.

The family remain anonymous by order of the tribunal, but the detailed biographical information in the judgment rather defeats the purpose. The tribunal should consider amending it if anonymity is important here.

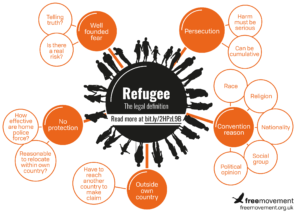

The Refugee Convention does not offer protection from social conservatism per se. There is no protected right to enjoy a socially liberal lifestyle.

The Convention may however be engaged where

(a) a ‘westernised’ lifestyle reflects a protected characteristic such as political opinion or religious belief; or

(b) where there is a real risk that the individual concerned would be unable to mask his westernisation, and where actors of persecution would therefore impute such protected characteristics to him.

One Response