- BY Sonia Lenegan

Unlawfully withdrawn asylum claim results in quashing of trafficking reconsideration refusal

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The High Court has held that an unlawfully withdrawn asylum claim can amount to exceptional circumstances meaning that an extension of time should be granted for a reconsideration request of a trafficking decision. The case is R (KM) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2024] EWHC 2870 (Admin).

Background

The claimant is an Albanian national who arrived in the UK on 30 October 2022 and was detained on arrival. He claimed asylum and was referred into the National Referral Mechanism to consider whether he was a victim of trafficking. A positive reasonable grounds (first stage) decision was made on 23 December 2022 and he was released from detention on 6 January 2023.

The claimant’s substantive asylum interview was scheduled for 25 January 2024. The claimant did not attend and his on 6 February 2024 his asylum claim was treated as implicitly withdrawn. On 14 February 2024 a negative conclusive grounds (second stage) decision was made.

The claimant instructed solicitors and a reconsideration request was made on 10 April 2024. This was rejected on 15 April 2024 on the grounds that it had been made outside the one month time limit referred to in the Modern Slavery Statutory Guidance for England and Wales and there were no exceptional reasons for an extension of time to be granted.

The guidance had been amended on 12 February 2024 and requests for reconsideration of a negative conclusive grounds decision were given a time limit of one month unless there were exceptional circumstances. Where an extension of time was requested, the guidance states that this should be accompanied by an explanation for the delay, how the new evidence was material and why it had not been provided earlier.

The judicial review

The judicial review challenged the withdrawal of the asylum claim on 6 February 2024 as well as the refusal to reconsider the negative conclusive grounds decision dated 15 April 2024. In relation to the withdrawal, the claimant submitted that the Home Secretary had failed to consider the medical reasons the claimant had missed his interview and/or had unlawfully failed to follow the policy.

The conclusive grounds challenge was that the Home Secretary had wrongfully considered that there had been no explanation for the delay in making the reconsideration request. It was also argued that the procedure was unfair as the Home Secretary had not made sufficient enquiries before making the decision, in a context where anxious scrutiny was required.

On 15 May 2024 the Home Secretary filed an acknowledgment of service, conceding the withdrawal element of the claim and agreeing to reinstate the claimant’s asylum claim. The decision to refuse the reconsideration request was maintained on the basis that the claimant had not shown that there were exceptional circumstances for an extension of time.

The claim was listed for a rolled up hearing on 31 October 2024. The High Court considered that there were five questions to be answered:

i) Question 1. Was the CG reconsideration refusal decision unlawful on the basis that it failed to take into account a relevant consideration, namely the fact that the Claimant had indeed provided an explanation for the lateness of his reconsideration request?

ii) Question 2. Did the Defendant, in making the CG reconsideration refusal decision, fetter his discretion by adopting an unlawful approach to the question of whether a change of solicitor could ever amount to an exceptional circumstance?

iii) Question 3: was the CG reconsideration refusal decision otherwise irrational / unfair on Tameside grounds?

iv) Question 4: Is it open to the Claimant now to mount a freestanding challenge to the 14 February negative CG decision, in light of (a) the failure to identify that decision (as opposed to the later CG reconsideration refusal decision) as a target, or seek any remedy in relation to it, in the claim form; and (b) the Claimant’s failure subsequently to apply to amend the claim form so as to include a properly pleaded claim against the CG decision; and/or (c) the principle, if relevant, of alternative remedy?

v) Question 5: If the answer to Question 4 is “yes”, was the CG decision unlawful on Tameside grounds?

On question 1, the court rejected the claimant’s assertion that a reasonable explanation had been given for the delay, as the claimant had only just instructed his solicitors and they had received the conclusive grounds decision on 25 March 2024. The court criticised the lack of evidence of what had happened between the negative conclusive grounds decision of 14 February 2024 and the claimant instructing his new solicitors.

Question 2 was also decided in favour of the Home Secretary as the court said that changing solicitors was not itself enough to justify an extension of time and the Home Secretary “was not saying, and it would not be fair to infer that he considered, that a change of solicitors could never give rise to exceptional circumstances”.

In deciding question 3, the judge said that because the consequences of a person not being found to be a victim of trafficking can be very serious, anxious scrutiny was required when considering this question. The court again criticised the lack of the lack of explanation given by the claimant.

However, the judge considered that the unlawfully deemed withdrawal of the claimant’s asylum claim was significant:

- That is not, however, the end of the matter. I have been troubled in this case by the potential relationship between “Ground 1” (which is technically no longer live, as a result of the concessions to which I have referred) and “Ground 2”, part of which I am now considering. The Defendant took the very significant step, on 6 February 2024, of deciding to treat the Claimant’s asylum claim as having been withdrawn by the Claimant. The reason given was that the Claimant had failed to attend the 25 January 2024 asylum interview. But this was plainly unlawful; it overlooked the fact that the Claimant had a perfectly valid, and fully evidenced, reason for not attending, which he had promptly communicated to the Defendant on 26 January 2024. It is unsurprising that the asylum withdrawal decision was eventually reversed.

- But it was not reversed immediately, and at the time of the CG reconsideration refusal decision, it had not yet been reversed. The question that arises is this: to what extent does the illegality and unreasonableness of the asylum withdrawal decision affect (or infect) the subsequent CG reconsideration refusal decision? I accept that asylum decisions, and trafficking decisions, are different, as Mr Way submitted. Asylum is primarily about whether a person has a well-founded fear of persecution in his home country, such that it would be a breach of the Refugee Convention to return him there. Trafficking raises different legal questions, under a different Convention. It has an important bearing on the kind of support a person might need to receive whilst they are present in the UK. But the two processes are potentially related, and often will be, e.g. where, as in this case, the asylum claim and the trafficking claim arise out of the same basic alleged facts.

- It is striking that on 4 April 2024 the Defendant stated in terms that the Claimant’s failure to attend the 25 January 2024 interview had resulted in “the asylum withdrawal decision and the outcome to the modern slavery Conclusive Grounds consideration.” (emphasis added). That language strongly suggests that the Defendant was under the impression, when making the CG decision, that the Claimant no longer wanted to claim that he had a well-founded fear of persecution at the hands of criminal gangs in Albania and that this had affected the outcome of the trafficking enquiry.

The court found that if the asylum claim had not been unlawfully treated as withdrawn then the trafficking decision may have been different, not least because the claimant would have had a substantive asylum interview during which he would have been able to explain his case in full and answer any concerns raised by the decision maker.

The judge said that “any rational decision maker properly understanding the basic factual and legal situation on 15 April 2024 would have appreciated that this was an exceptional case because the CG decision had proceeded on an erroneous basis” and he quashed the reconsideration refusal decision. Questions 4 and 5 were also resolved in the Home Secretary’s favour.

Guidance changes

The Home Secretary was asked by the court to explain what had been done to communicate the new deadline for reconsideration decisions introduced in the February guidance. The response was that this had been done “E.g. by way of the newsletter from the Defendant’s Modern Slavery Unit dated 12 February 2024 directing stakeholders to paragraphs 14.212-14.230 of the updated Guidance”.

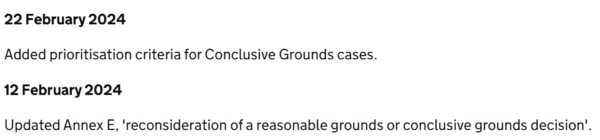

I think it is worth highlighting what the updates page says:

I don’t think that communicating these important changes properly only to a limited group of people is anywhere near sufficient. It would be a simple matter to mention substantial changes on the updates page itself, or to flag up more detail about the changes in the relevant section of the guidance itself. The Home Office must be more transparent.

Conclusion

It is quite nice to see these unlawful withdrawal decisions starting to cause problems for the Home Secretary. More please.

SHARE