- BY Jon Featonby

Understanding the Home Office’s problem with asylum decisions

Table of Contents

ToggleThere have been lots of different numbers and statistics relating to the UK’s asylum system mentioned over the last week. One of these is the backlog of people waiting for an initial decision on their asylum claim.

Depending on whether or not people include dependents, the backlog of initial decisions on asylum claims can range from around 100,000 to 122,000 (and you’ll also find a different number depending on where in the Home Office’s published statistics). Whichever number is chosen, it’s big. And there is a significant impact both on the people who are left in limbo waiting for a decision and on the overarching health of the asylum system.

There have also been countless references to the UK’s “broken asylum system” from all sides over the last week. While there are very different views on what a fixed system would look like, a general point of agreement is that people would get timely decisions on their claims and those decisions would be right first time. At least where timely decisions are concerned (I don’t intend to provide any analysis of whether these are right first time), the UK’s asylum system is in a pretty sorry state.

In part, the circumstances surrounding the awful conditions that men, women and children have endured at Manston and Western Jet Foil in Kent are a consequence of decisions taken as a result of the impact of the backlog. If there are more people in the system for longer periods then more Home Office accommodation is required. And the failure to expand dispersal housing has left the department and its contractors reliant on hotels and ex-military sites.

There has been less of a focus on why the backlog is as large as it now is. There are always going to be outstanding cases, otherwise all decisions would be made immediately. But an efficient asylum system would make around the same number of decisions as there are new applications coming in.

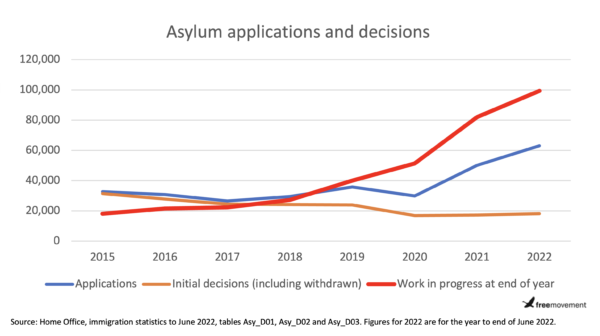

Since 2015 the gap between those two figures has grown and it continues to widen as the number of decisions fail to keep up with the number of applications. Indeed, as the backlog has grown the overall number of decisions being made has fallen.

There can be a tendency from some quarters to suggest it is because of the strain put on the system from the higher numbers of people now arriving via small boats across the channel, 93% of whom claim asylum in the UK as the Home Affairs Select Committee was informed last week. But this explanation ignores the reality that the backlog has been growing exponentially for more than six years.

At the end of 2015 18,111 cases were waiting for an initial decision. This had doubled to 40,032 three years later. It took just two years for it to double again to nearly 82,000 by the end of 2021. Six months later there were an extra 17,411 cases in the backlog, bringing the total to 99,419 by June this year.

So what has caused this increase? As with most things, there isn’t one simple answer. I’m going to highlight three developments that have impacted the backlog over that time and one more recent change that could make things worse.

I’m not going to cover the impact the Covid pandemic had. It’s clear this slowed down decision-making as interviews couldn’t take place and the Home Office infrastructure had to adapt to home working. But it’s also noteworthy that the number of asylum applications also dropped, at least over the first year of the pandemic.

2016 – Home Office staffing shortage

Key to being able to make timely decisions is the recruitment and retention of well-trained asylum decision-makers. The more people able to make decisions, the more decisions should be made. In 2016, there was a significant fall in the number of people making decisions on asylum. For the financial year 2014/15, there were 409 Home Office civil servants carrying out interviews and making asylum decisions. But, according to the Home Office’s transparency statistics, this fell by more than a third over the following year to just 260 people.

This was an issue raised by David Bolt, then the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, in his 2017 inspection report on asylum intake and casework:

“The number of DM [decisions makers] who were available to conduct interviews and make decisions, referred to by the Home Office as ‘active’ DMs, fell from 319 in January 2016 to 228 in July 2016.”

Mr Bolt went on to say that by March 2017, decision-making numbers were up to 352. However, he raised concerns about the training that was provided:

“These ‘new’ DMs told inspectors that their initial training had not prepared them adequately to do their job, and they had relied on the guidance and support from more experienced colleagues and “on the job” learning to develop the necessary skills and knowledge.”

The Home Office’s statistics show the impact this had. In 2015 the department made 28,623 decisions on asylum applications. This fell by a quarter to 21,269 in 2017 and has never recovered to previous levels.

2018/19 – dropping the six month service standard

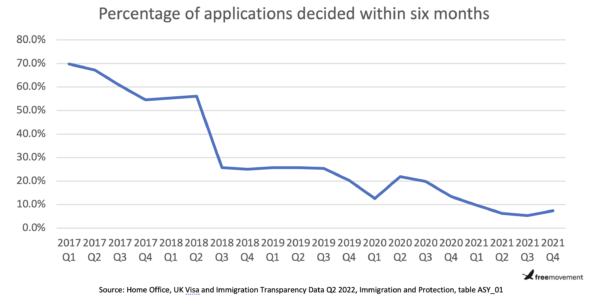

Following a report by the Home Affairs Select Committee that was critical of the delays in asylum decision-making, in April 2014 the Home Office introduced a service standard that 98% of straightforward asylum applications should be decided within six months. Of the claims that were submitted from March 2014 to the end of the year (including those deemed non-straightforward), 8% received a decision within six months.

The six-month service standard was removed in January 2019, and Caroline Nokes, the Immigration Minister at the time, set out the reasons in a letter to the Home Affairs Select Committee. While there were many issues with the six-month service standard, especially for the increasing number of people whose claim was classified as “non-straightforward”, removing it had an immediate impact on the speed of decision-making. Of asylum claims submitted in the second quarter of 2018, 56% received a decision within six months. For those submitted in the next quarter, only 25.6% received a decision within that timeframe. That statistic has not risen above that level since.

Leaving the EU’s Dublin System

From the data, it’s quite clear that something happened around the time the UK left the Dublin system. This was set out in the Statement of Changes to the Immigration Rules (HC 1043) that came into force at 11pm on 31 December 2020. These changes broadened the UK’s domestic legislation on when asylum claims could be treated inadmissible, in particular when the Home Office believes someone should and could have applied for asylum elsewhere.

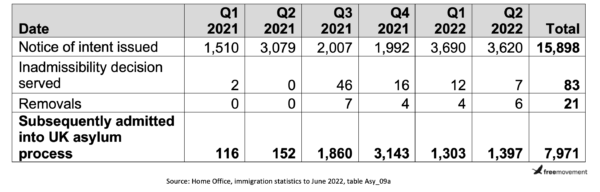

Alongside the changes to the rules, there were new processes put in place and updated inadmissibility guidance was published. As part of this process, if it is believed someone’s claim could potentially be inadmissible, then the individual is given a “notice of intent” while the Home Office gathers more evidence and also tries to get an agreement with a third country for a transfer. An actual inadmissibility decision can only be served once that agreement is in place.

There is no set timescale in place for how long the Home Office has to seek this agreement. Instead, the guidance says:

“the inadmissibility process must not create a lengthy ‘limbo’ position, where a pending decision or delays in removal after a decision mean that a claimant cannot advance their protection claim either in the UK or in a safe third country.”

And then adds:

“If… it is not possible to make an inadmissibility decision or effect removal following an inadmissibility decision within a reasonable period, inadmissibility action must be discontinued, and the person’s claim must be admitted to the asylum process for substantive consideration.”

The guidance doesn’t define “a reasonable period” but does state that the Home Office expects six months to be long enough in most cases. One of the problems the Home Office faces is that the only agreement in place with a third country is the one with Rwanda. The issues with that deal are well documented.

In the first 18 months of the inadmissibility rules being in place, only 83 inadmissibility decisions were served despite nearly 16,000 notices of intent being issued. Half of those given notices of intent have already now had their cases admitted for substantive consideration in the UK. In effect, the inadmissibility rules have only resulted in adding a further six-month delay for many claims, just adding to the backlog.

Impact of the backlog

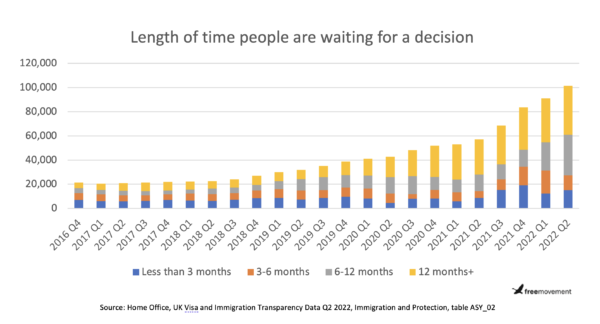

The impact of the backlog growing over time, rather than being an immediate reaction to a sudden increase in applications, is that it has resulted in much slower decision-making over a number of years. At the end of June this year, more than 40,000 cases in the backlog for initial decisions were older than a year. Depending on which Home Office stats you use, either 72,500 or 74,000 cases were older than six months. Of the claims submitted in 2021, 93% were still awaiting an initial decision by the end of June this year and over half of the other 7% had been withdrawn.

This leaves people in the asylum system for ever-increasing periods, reliant on the asylum support system. As well as the human impact that organisations like the British Red Cross and others see every day in our work, this also means people are in asylum accommodation for ever-increasing periods. This creates a bottleneck which in turn leaves the Home Office increasingly reliant on hotels and facilities like Manston.

Future problems

And the really depressing thing is that the backlog is only likely to get worse. The Nationality and Borders Act contains provisions that will further impact on asylum decision-making times. This includes the changes in section 12 bringing in differential rights and entitlement for refugees recognised through the asylum system depending on how they entered the country.

This process involves putting refugees into either “group 1” or “group 2”, adding a further step for decision-makers and refugees at the end of the process. The assessing credibility and refugee status guidance has this to say for decision-makers:

“Any individual who you deem to be a Group 2 refugee must be provided with an opportunity to rebut this provisional grouping. You must provide the claimant with a minimum of 10-working days to provide an explanation of why they are not a ‘Group 2’ refugee. You may provide an extended period of time for a response, including following a request from the claimant, as long as the extension is proportionate to the particular circumstances.”

The guidance doesn’t say what happens after that point, including the time frame the decision maker has to respond to any rebuttal. But any time period will just increase the length of time people spend in the asylum system, further adding to the backlog.

So what next?

I don’t think there are simple solutions to the problem. More capacity in the Home Office to make more decisions is a key part. The Home Affairs Select Committee was told last week that there are now 1,073 decision-makers, an increase of 584. But in their response to the same committee’s report on Channel Crossings, the Home Office said that “it can take up to 12 to 18 months for a decision maker to become fully proficient in their work”. So this will take time to have an impact.

In the meantime, a realisation that recent policy changes to the asylum process are only going to exacerbate the issue is needed. An urgent rethink would be a good idea for all involved. And finding ways of fast-tracking some claims, especially for people from nationalities with high grant rates that are almost certainly going to be given a status, might help the Home Office get on top of a backlog that will otherwise just keep growing.