- BY Iain Palmer

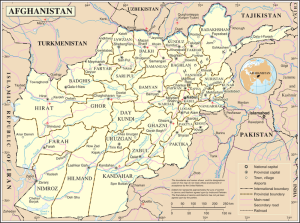

Unattended children in Afghanistan

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

This is the week in which Human Rights Watch reported that ‘Children deported to Kabul will face horrible risks‘ and Amnesty International reported that at least 28 children had died in the IDP camps around Kabul as result of the freezing winter conditions and lack of food. Yet to respond to these and other reports of the appalling circumstances within Afghanistan, the UKBA can be said to still think that once a dateline of 18 years of age is crossed or there was once disclosed even the most tenuous of family links Kabul, a young Afghan can in many circumstances be returned to Kabul. Where we often disagree with the UKBA’s stated positions on a particular country situation we can at times at least understand them. The UKBA’s position here cannot be understood. Now is not the time to return minors or young people to Afghanistan. The new decision in AA (unattended children) Afghanistan CG [2012] UKUT 0016 (IAC) is certainly a long way off from forcing the UKBA into any policy initiative which favours minors or those just over the 17½ year threshold, so much is clear from the neutrally toned headnote:

This is the week in which Human Rights Watch reported that ‘Children deported to Kabul will face horrible risks‘ and Amnesty International reported that at least 28 children had died in the IDP camps around Kabul as result of the freezing winter conditions and lack of food. Yet to respond to these and other reports of the appalling circumstances within Afghanistan, the UKBA can be said to still think that once a dateline of 18 years of age is crossed or there was once disclosed even the most tenuous of family links Kabul, a young Afghan can in many circumstances be returned to Kabul. Where we often disagree with the UKBA’s stated positions on a particular country situation we can at times at least understand them. The UKBA’s position here cannot be understood. Now is not the time to return minors or young people to Afghanistan. The new decision in AA (unattended children) Afghanistan CG [2012] UKUT 0016 (IAC) is certainly a long way off from forcing the UKBA into any policy initiative which favours minors or those just over the 17½ year threshold, so much is clear from the neutrally toned headnote:

(1) The evidence before the Tribunal does not alter the position as described in HK (Afghanistan), namely that when considering the question of whether children are disproportionately affected by the consequence of the armed conflict in Afghanistan, a distinction has to be drawn between children who were living with a family and those who are not. That distinction has been reinforced by the additional material before this Tribunal. Whilst it is recognized that there are some risks to which children who will have the protection of the family are nevertheless subject, in particular the risk of land mines and the risks of being trafficked, they are not of such a level as to lead to the conclusion that all children would qualify for international protection. In arriving at this conclusion, account has been taken of the necessity to have regard to the best interest of child.

(2) However, the background evidence demonstrates that unattached children returned to Afghanistan, depending upon their individual circumstances and the location to which they are returned, may be exposed to risk of serious harm, inter alia from indiscriminate violence, forced recruitment, sexual violence, trafficking, and a lack of adequate arrangements for child protection. Such risks will have to be taken into account when addressing the question of whether a return is in the child’s best interests, a primary consideration when determining a claim to humanitarian protection

This superbly crafted determination from Mr Justice Owen and UTJ Jarvis provides us with as full and honest an appraisal of the current situation for young returnees as I have seen in the recent past. AA was from Kabul Province and arrived in the UK as an unaccompanied minor in May 2009. His claim for asylum was fear of persecution on return to Kabul as an unaccompanied minor and/or by reason of political opinion imputed to him by virtue of anti-Taliban family connections and that he himself had been among a group who sang an anti-Taliban song at a public gathering. The Tribunal allowed the appeal, ruling that he has proved that there was a real risk of being persecuted or of other serious harm if returned to his home area or to Kabul.

Not unusual facts but even so these are a few reasons why I think the decision deserves to be fully digested:

i. It reminds us, and we all sometimes need reminding, to always look beyond the headnote of any reported case. The summary provided above simply does not do justice to the wealth of findings and observations made within the body of the determination which can be used to the benefit of claimants.

ii. It includes a fabulous summary of all current learning on the proper approach to the assessment the evidence of minors. I haven’t seen this in such a useful form in a single determination or judgement before. Very much worth reading and reciting ad nauseum until your particular audience understands that things are different — very different — when dealing with children.

iii. It reveals that the situation in Kabul and Afghanistan generally is deteriorating and has worsened since HK.

iv. It serves a reminder that even if a young person is from Kabul or Kabul Province (where the UKBA often states adequate protection exists), this does not permit a less stringent examination of risk when they would be returning unaccompanied.

v. It reiterates how vulnerable unaccompanied children are to sexual exploitation and force recruitment and, as per Court of Appeal in DS (Afghanistan) the UKBA is itself under an obligation to attempt proactively to trace the family members of unaccompanied minors.

This is a very useful case but what to my mind is so commendable is that each and every stage of Tribunal’s fact finding process involves careful consideration of the correct approach to the assessment of a child’s evidence. Of course I want this to be as an inclusive a post as possible, but maybe only the refugee lawyers amongst us will understand why it’s so refreshing to see something done so well.

2 responses

Very much agree with your comments. If we are to have the ‘exotic’ country guidance mechanism as part of our domestic asylum process, as unusual as it might be regarded in other countries, then this should surely be regarded as an example of good practice in the Tribunal. A big improvement on HK, which was quite patently based on out of date country information.