- BY Colin Yeo

UK spends one third of international aid budget on domestic asylum costs

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

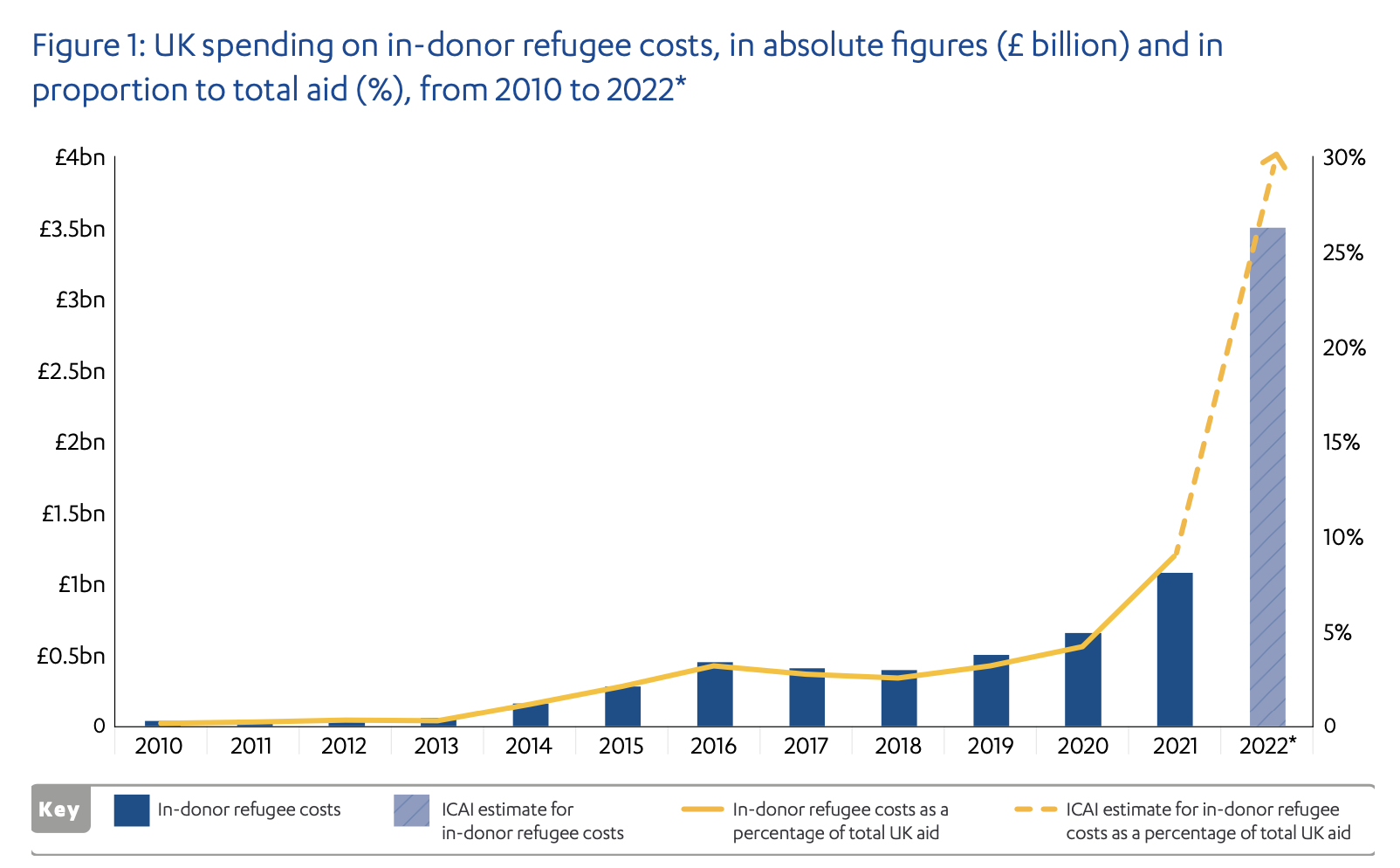

A new report by the international aid spending watchdog has revealed that the Home Office spent one third of the UK’s international aid budget on domestic asylum costs, leading to severe cuts to genuine international aid programmes. The Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) found that the permission given by the government to the Home Office to spend an “unlimited proportion” of the international aid budget was responsible for the “limited UK response” to the Pakistan floods in 2022 and developing famine in the Horn of Africa.

Meanwhile, as the BBC recently reported, private firms and hotels here in the UK are making considerable profits from housing asylum seekers stuck waiting in the growing asylum backlog. Essentially, the “international” aid budget is being diverted by the Home Office into the pockets of the UK private sector.

Under international aid rules, the first year of some of the costs associated with supporting refugees and asylum seekers who arrive in the UK (or any other country) can be reported funded as if it were international aid. This has always been a controversial rule because money used for this purpose never actually leaves the “donor” country.

Home Office overspending

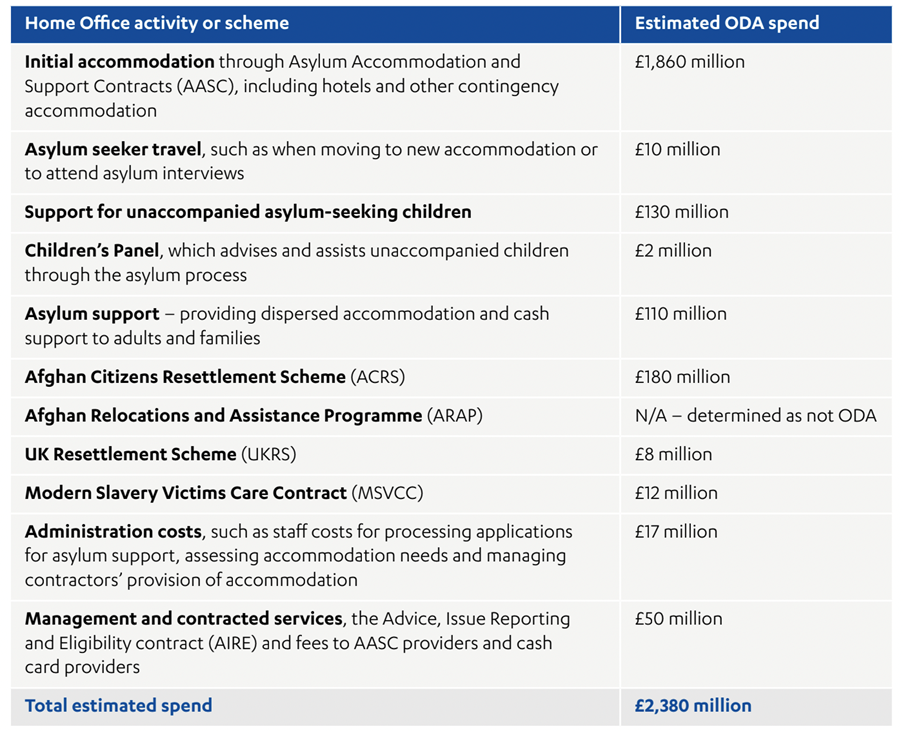

In its review, the committee estimates that in 2022 around £3.5 billion of the UK’s aid budget, which is around one-third of the total budget, was spent on refugees and asylum seekers in the UK. This represents a massive increase on previous years. Of that, around £2.4 billion was spent by the Home Office (the rest by other government departments). In 2019 this figure was around £1 billion, and until 2016, it remained under £500,000.

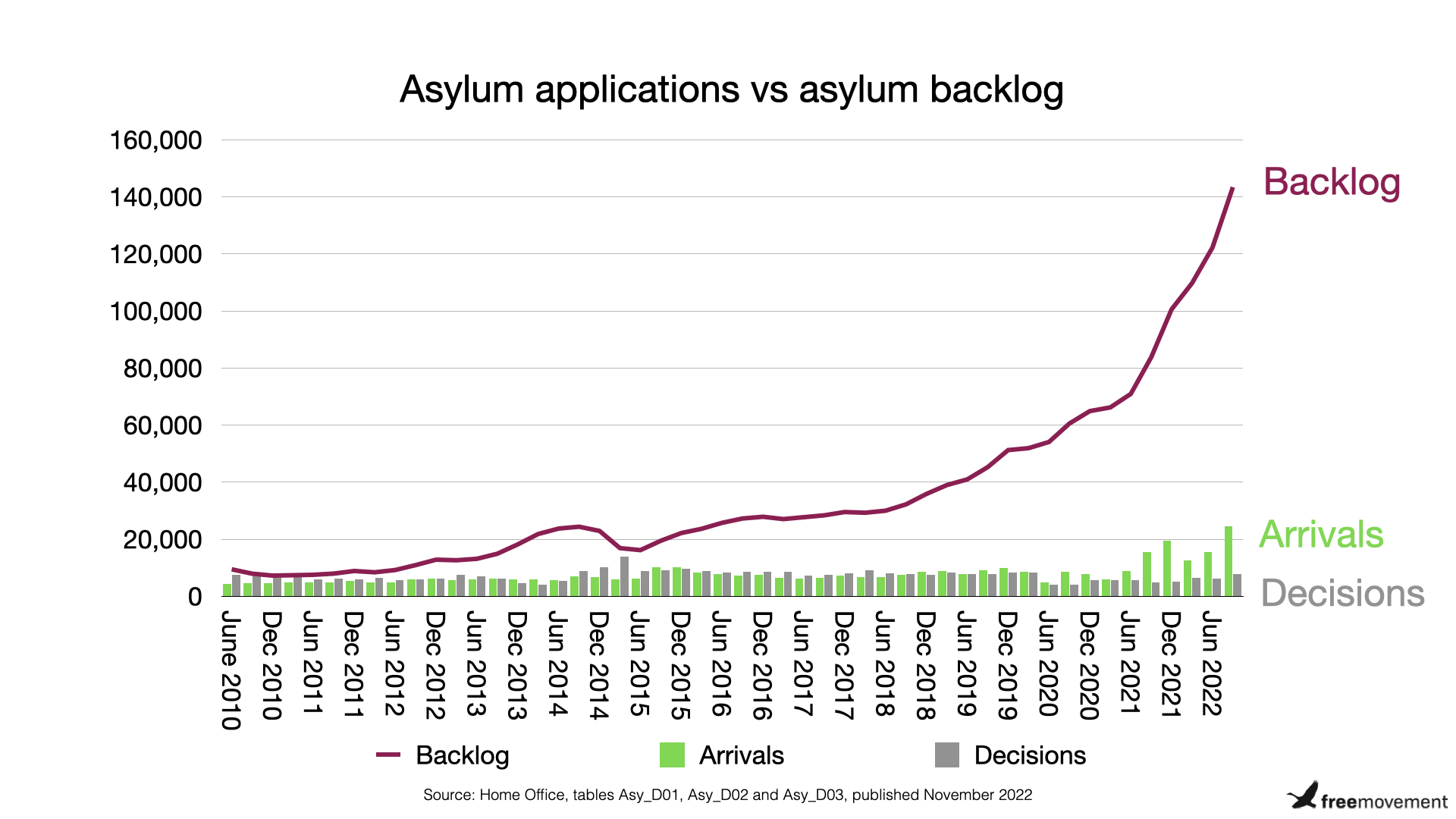

The short term approach of the Home Office to accommodating asylum seekers has led to “spiralling” costs, exacerbated by the growing asylum backlog. Spending has also been allocated in this way to the Ukraine and Afghanistan schemes.

The commission report found that the Home Office does not effectively oversee or monitor value for money. Even its recently introduced improved monitoring systems are “not appropriate for the task of ensuring that the right outcomes are being reached and that value for money is achieved”. Contracting is currently run by a “significantly under-resourced” team without the necessary staff or skills and using badly out-of-date key performance indicators. In short, there is no effective oversight of whether contractors provide value for money.

Due to a shortage of accommodation, the Home Office has housed refugees and asylum seekers in hotels at a reported cost of £6.8 million per day in October 2022. As of 14 March 2023, the Home Office has used 386 hotels around the UK to host asylum seekers, up from around 200 in October. In addition, in October the Home Office was using an extra 64 hotels to accommodate Afghan refugees.

And it’s not just accommodation the Home Office is spending money on. The number of destitute refugees and asylum seekers arriving in the UK in 2022 has increased to more than 90% compared to before the Covid-19 pandemic, where the figure was only around 50%. This means there is a significant increase in the number of people claiming additional support.

Ineffective resourcing and monitoring, even with this emergency provision of hotel accommodation, has also led to refugees in such accommodation – particularly women and girls – facing “significant risks”, especially of gender-based violence and harassment. Third-party contractors do not have clear enough obligations to address safeguarding issues systematically, and safeguarding apparently does not feature in their contracts with the Home Office.

The unlimited spending cap disincentivises the Home Office from making efficient and effective long-term plans. The Home Office is unable to provide accurate forecasts of its spending and it is no wonder that they have no real incentive or requirement to control their costs when they are spending another department’s money.

The effects of the Home Office failings are also indirect. Gaps in provision have also sucked resources out of the already over-stretched UK charity sector. The commission found many examples of charities and community groups, hotel management and concerned individuals providing additional support to fill key gaps, such as donating winter clothes.

Mismanagement of Home Office schemes

Meanwhile, high-profile schemes for Afghans and Ukrainians are relatively well resourced. These too can be partially funded by the international aid rule and the second largest contributor to the Home Office’s £2.4 million bill is the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS). Under this scheme, since January 2022, 6,292 people have been given indefinite leave to remain through the UK’s evacuation programme, and four people have arrived in the UK through UNHCR referral.

These schemes have “crowded out” other categories, particularly schemes for resettling refugees identified by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The spending is allocated irrespective of the actual needs of those concerned; it is a political hierarchy. The table below sets out the Home Office’s costs, paid for using the aid budget, during 2022:

Not all schemes come solely under the Home Office’s remit. The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and the Home Office jointly run the Homes for Ukraine scheme, which was allocated £520 million from the aid budget in 2022.

The commission report finds a lack of co-ordination between departments. In fact, competition between those running the different visa schemes actually increased overall costs:

“we heard form several stakeholders, including within government, that different parts of the Home Office operating different schemes source their accommodation separately and, at times, found themselves competing for the same hotel contracts, driving prices up.”

Impact on UK aid programmes

Genuine international aid spending had to be cut as a consequence, “despite the risk to its partnerships and the many people around the world who rely on UK development and humanitarian aid”.

The UK’s budget for aid provided to other countries is now considerably smaller than its spending on refugees and asylum seekers in the UK. Cuts of 30% to the international aid budget are forecast for next year.

The UK is now unable to play a leading role in international responses to global crises. This can be seen in particular in what the commission described as the “limited” responses to the disastrous floods in Pakistan in 2022 and the worsening drought in the Horn of Africa, which is predicted to cause widespread famine in 2023. UK aid to Pakistan will be a mere £36 million as of January 2023, compared to France’s £316 million and Germany’s £74 million. Meanwhile, despite the looming crisis, UK aid in the Horn of Africa will actually be lower in 2022-23 at £156 million, compared to £221 million in 2021-22. And that is way down on £861 million spent on the 2017 drought.

UK overseas aid is now helping “far fewer people” because when the money is spent in the UK it does not stretch as far. It also runs counter to a key humanitarian principle that “humanitarian action should give priority to the most urgent needs”.

How can this be fixed?

It is not the first time that the Home Office has been criticised for its failings in this area. The commission noted that poor value for money is a “consistent theme in oversight by the Public Accounts committee, Home Affairs Committee, National Audit Office and Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration”.

Urgent recommendations to reduce hotel use made well before the accommodation crisis last year, but the committee found no evidence that the Home Office had produced such plans. They also did not find any evidence that the Home Office had improved its contract management practices in response to earlier recommendations. Ignoring recommendations seems to be a recurring theme. Ultimately, the department needs to strengthen its learning. It needs to become more deliberate, urgent and transparent with how it addresses findings and recommendations from scrutiny reports.

The report recommends introducing a cap to the amount of the aid budget the Home Office is permitted to spend and improving the value for money it gets out of the money it does spend. Even just a little coordination between different Home Office departments would begin to help. They should resource activities by community-led organisations and charities’ sub-contractors to support newly-arrived refugees and asylum seekers as it currently relies too heavily on organisations and individuals going “above and beyond” to provide adequate services. The Home Office should also ensure that refugee support is “more informed by humanitarian standards”, including improving safeguarding.

Looking ahead to the Rwanda plan, the cost of detention in the UK cannot come out of the aid budget, nor can the costs of supporting people who are not permitted to claim asylum. However, it is not clear whether aid provided to Rwanda as part of the refugees-for-cash exchange will come out of the international aid budget or not.

The commission concludes that “it is clear that measures to speed up processing could help reduce emergency accommodation costs, thus lessening the disruption to the aid programme”. In the meantime, coordination and cooperation within the Home Office, including listening to external review recommendations, and to colleagues from different internal teams, is a simple way to cut costs and accurately review spending habits.

SHARE