- BY Joanna Hunt

Why can’t politicians get over the idea of an Australian-style immigration system?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleFor politicians with an agenda to push and votes to win, talking up an “Australian-style points based system” seems like a catchy, quick-fix solution to public anxiety over immigration. During the referendum campaign it was a popular trope of the leave campaign, trotted out endlessly, with little explanation as to what it meant, how it would work or more importantly how it differs from the UK’s current managed migration system.

Boris Johnson is the latest to follow this well trodden path, previously taken by Gordon Brown, Nigel Farage and Michael Gove. He was quick to extol the virtues of an Australia-style system during his campaign for the Conservative leadership. Once ensconced in office, Johnson announced during his first parliamentary statement that his government would make the instigation of a points based system the centrepiece of its immigration reforms.

So what is an “Australian-style point based system?”

The premise of a points based system, whether Australian or otherwise, is to score visa applicants according to a number of objective personal attributes such as age, competency, qualifications and experience. The person is awarded a certain number of points for meeting each of the criteria. Applicants then add up their score and if they are above the minimum number required, they will be granted a visa and often permanent settlement in the country concerned.

Applicants for an Australian Skilled Independent visa do not need a sponsor but do need to be able to score 65 points from a points table. Being aged 18-25 scores 25 points, having proficient English scores 10 points, having eight years’ work experience scores 15 points and having an undergraduate degree is 20 points — getting to the magic 65.

But there are multiple ways to reach the threshold. Somebody with less than three years’ work experience scores zero points, but can make it up by with “superior” English (20 points). In the UK, by contrast, you either meet all the criteria for a visa or you don’t.

The key is that the visa is granted due to the personal, merit-based attributes of the applicant rather than them having a specific job offer in a country. It is a way of attracting skilled workers who are likely, so the thinking goes, to assimilate to a new social and cultural environment.

If this is all sounding very familiar, that is because it is. As immigration lawyers know (and regularly shout at the TV every time an MP mentions it) the UK has theoretically had a “points based system” for some time.

Wait, we already have a points based system?

In 2007 the then Labour government announced measures to overhaul the immigration system which regulated how non-EU migrants could work in the UK. The country had started to feel the effects of the influx of EU labour from new members like Poland and the government wanted to look responsive to the growing anxiety around immigration by showing it could control the number of migrants arriving in the UK to look for work.

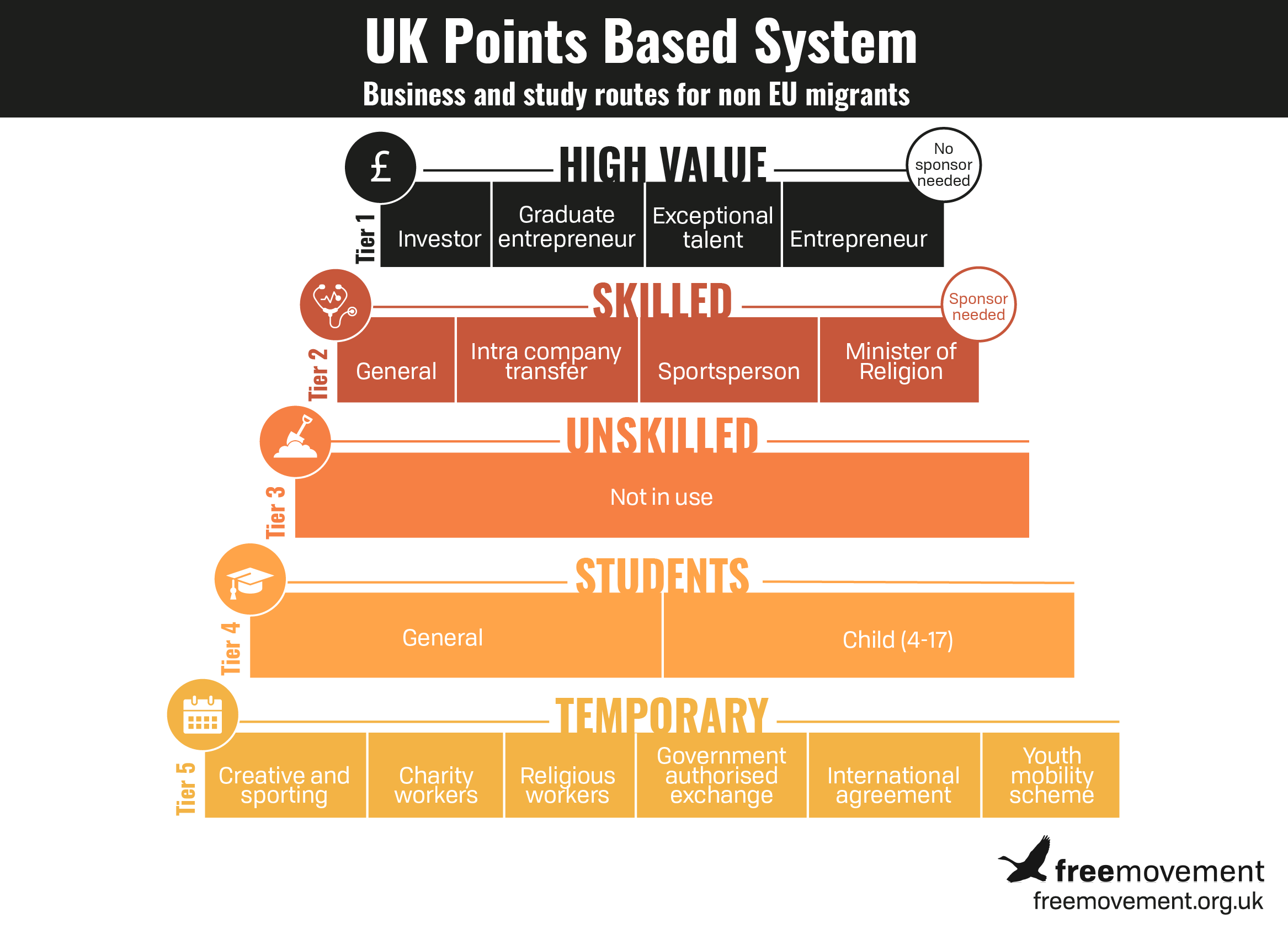

The end result was the creation of a points based system which still exists, in name at least, to this day. A section of the Immigration Rules called — you guessed it — “The Points Based System” governs the majority of work visas available to non-EU workers. It consists of five ‘Tiers’, each devoted to a general category of migrant.

Then why do politicians keep saying we need an Australian-style system?

Once up and running, the UK’s version of a points based system never really operated in a truly merit-based way, thanks to furious lobbying from industries which watered down the requirements. The sole category which was merit-based, the Highly Skilled Migrant Programme which later morphed into Tier 1 (General), was closed in 2011. This was due to fears that applicants were not working in highly skilled jobs and were instead filling menial roles.

Since then, the system has been points based in name only. Each tier has certain mandatory criteria, such as a maintenance requirement or an English language criterion, just like other categories of the Immigration Rules. The specific visa will have its own requirements — investors need a certain amount of hard cash, youth mobility applicants need to be under 31, and many others require sponsorship or endorsement of some sort.

If an applicant can demonstrate that they meet the criteria they will automatically accrue the relevant amount of points. If, for example, an applicant doesn’t meet the maintenance requirement, there is no way to make it up elsewhere. The scoring is largely symbolic.

Politicians are magnetically attracted to the phrase “Australian style points based system” because it plays well in focus groups. John McTernan, an adviser to Tony Blair, says that was what Labour found as far back as the 2005 general election, while academic researchers found last year that voters repeatedly cited Australia, unprompted, when asked about immigration.

Why Australia? In part because Australia is thought to be tough on migration generally, a result of media coverage of asylum seekers being put in camps on remote Pacific islands. Some say that another cause is Australia being understood by many voters to be a predominantly white country that does not admit many ethnic minority migrants.

CJ McKinney

With the introduction this year of the Innovator and Start-up categories in Appendix W to the Immigration Rules, there are signs that the government is starting to create work based visa rules outside of the so-called points based system. But it is not on its way out just yet. The government’s immigration white paper — a blueprint for migration after Brexit — made clear that the existing system for economic migration will be maintained and extended to include EU citizens.

Post 2021, Europeans will have to negotiate the Tier 2 work visa system in order to work in the UK, and will require an employer with a sponsor licence willing to give them a job. The white paper suggested relaxing the Tier 2 system by getting rid of the annual quota on Tier 2 (General) visas and the Resident Labour Market Test. It was clear however that the new immigration system post Brexit would still operate within the structure of the points based system we have now.

What could a true points based system look like?

The Migration Advisory Committee has been instructed to investigate how such a system could be implemented in the UK, and is due to report back in January 2020. The committee’s recommendations are influential, so its report will give us a better idea of what the government might do. There are several considerations that its report is likely to reflect.

Cutting net migration – or not

The government first needs to be clear on exactly why we need a new points based system.

In recent times the Conservatives have been focused on using immigration reforms to cut net migration. If this is still the aim, then a points based system is not the way to go.

In other countries, points based systems are not used for reduction in net migration levels. As the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford puts it:

it is surprising to hear discussion of the points system as a tool to reduce migration. It has traditionally been used by countries with liberal migration policies seeking to admit more people than would come to the country through employer-sponsored migration alone… In Australia and New Zealand, which both have points systems, the share of the population that was born abroad had reached 28% by 2013 – roughly double the UK share.

Since Boris Johnson took office he has sought to distance himself from the net migration target. So if this has now been abandoned, this needs to be spelt out to the electorate and we need to understand the real purpose behind a new points based system so its success can be judged.

Relationship with existing work visa system

The second issue is how a new system will interplay with the current work visa categories.

The signs are that a new merit-based points based system will be in addition to, rather than a replacement for, the existing Points Based System and its various Tiers. If so, the new rules will have to be carefully drafted not to undermine the Tier 2 system. This places onerous reporting and record-keeping duties on employers, which they would be keen to avoid if an easier visa option is available.

One solution would be for a new points based system to operate as it does in Australia. There, the majority of migrant workers are still recruited via a sponsorship system, while the points based system provides a top-up for jobs where there are skills shortages or in regions which need to attract workers.

Fairness and non-discrimination

Next it is vital that a new points based system system is more fair and inclusive than it has been in the past.

Traditional points based systems provide a blunt, subjective and often discriminatory assessment of what merit actually means. The worth of a candidate is distilled down to a tick-box assessment of characteristics and achievements on a CV. They are simplistic — leading to a racial and gender based bias in favour of predominantly male applicants from majority white countries. Any age scoring element discriminates against talented older candidates who have skills that would benefit the UK.

The indications from the Migration Advisory Committee’s call for evidence are that we may simply end up with another rehash of Tier 1 (General). Annex A of the call for evidence asks respondents to rank a list of attributes in order of importance. This list includes the familiar criteria of points based systems; language, work experience, age, education and job offer. It seems unlikely, then, that the committee will be advocating a bold new direction.

Can’t we get past empty slogans?

Which leads us to the main problem with the repeated talk of an “Australian points based system”. It has become a convenient vote-winning slogan, an attempt to persuade the electorate that the UK’s immigration woes could be solved with a simple importation of an immigration system from down under. It distracts the public from the fact that the government has no real substantive policy ideas to reform our immigration system.

What is needed is more honest reflection on what we want our immigration system to do and what it should represent. For instance, should we have an immigration system that is focussed on filling jobs? Local areas are more positive about migration if newcomers create roots and become part of their local community. Applicants with family connections to a country also have “merit”: their social capital makes it more likely that they will commit to making a longer term impact to a host country.

With an election and a new government on the horizon, a lot may change. Given the dearth of equally catchy ideas from the other political parties, the buzz surrounding an Australian points based system means it is unlikely to go away anytime soon.

This article was originally published in June 2019 and has been updated to take account of developments since.

6 responses

Just bring back the HSMP – and that will be it. The best Highly Skilled program the UK has ever had.