- BY Free Movement

Tribunal obliged to seek out representation in Country Guidance cases

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

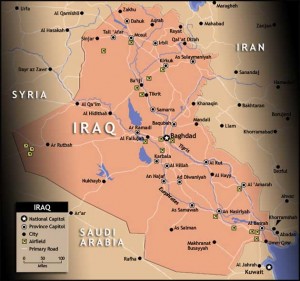

The Court of Appeal last week handed down a very interesting judgment on the need for ‘proper argument’ in Country Guidance cases, the obligation on the tribunal itself to seek to secure that proper argument and how far the tribunal determination process can morph from an adversarial to an inquisitorial one. The case is HM (Iraq) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2011] EWCA Civ 1536 and Richards LJ gives the leading judgment.

The Court of Appeal last week handed down a very interesting judgment on the need for ‘proper argument’ in Country Guidance cases, the obligation on the tribunal itself to seek to secure that proper argument and how far the tribunal determination process can morph from an adversarial to an inquisitorial one. The case is HM (Iraq) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2011] EWCA Civ 1536 and Richards LJ gives the leading judgment.

This was the case where the tribunal decided to plough ahead with a CG case on Iraq despite the appellants being unrepresented, in controversial circumstances, at the hearing. See previous blog coverage here and here.

On the need for proper argument, Richards LJ said as follows:

39. Whether or not country guidance determinations can properly be described as “declaratory” in nature, they have a status and significance comparable to that which declarations can have in public law cases, and it is just as important that there should be proper argument in them. “Proper argument” in this context encompasses not just argument on the law but also the drawing of relevant materials to the attention of the tribunal and the making of submissions as to the effect of those materials, so that the determination is based on as full and informed an analysis as possible. In the ordinary course that is achieved through both sides being legally represented. Indeed, on the analysis provided to us by Mr Fordham, there has been such representation for every country guidance determination save the one now before us.

…

42. The tribunal did what it could to try to secure legal representation for the appellants. It sought to have the question of public funding reconsidered and it asked the appellants’ former representatives whether they would act pro bono in the absence of public funding, but in each case it was met with a negative response. The tribunal might have approached the LSC directly, but there is nothing to suggest that it would have been any more successful than the appellants’ former representatives had been. The features of the legal aid system which precluded the continuation of public funding before the tribunal are deeply regrettable, all the more so when it is borne in mind that public funding was granted for the appeal to this court and that the overall cost to public funds will have been far greater than if funding had been continued at the time for the proceedings before the tribunal. Unsatisfactory as it was, however, the tribunal was faced with a position where none of the appellants was represented. It was also clear that none of the appellants would be in a position to make any material contribution of their own to the proceedings.

However, this wasn’t enough, apparently. Richards LJ goes on to suggest two further possibilities. The first was to ask UNHCR to make submissions, something UNHCR themselves said they would not normally do but had not technically ruled out. Anyone familiar with UNHCR London might think this was a somewhat unlikely possibility. More interestingly and potentially usefully Richards LJ then goes on:

45. The second possibility was to request the Attorney General to consider appointing an amicus curiae (advocate to the court). Those appearing before us were not aware of any instance in which an amicus has been appointed for the purpose of proceedings in the tribunal. I see no reason in principle, however, why such an appointment should not be made in an appropriate case. A memorandum from the Lord Chief Justice and the Attorney General on requests for the appointment of an advocate to the court is set out in Civil Procedure, vol.1, at pages 1144-1145. Even though it does not apply in terms to tribunal proceedings, its contents can readily be transposed to such proceedings. It states:

“3. A court may properly seek the assistance of an Advocate to the Court when there is a danger of an important and difficult point of law being decided without the court hearing relevant argument. In those circumstances the Attorney General may decide to appoint an Advocate to the Court.

4. It is important to bear in mind that an Advocate to the Court represents no-one. His or her function is to give to the court such assistance as he or she is able on the relevant law and its application to the facts of the case. An Advocate to the Court will not normally be instructed to lead evidence, cross-examine witnesses, or investigate the facts ….”

46. The situation before the tribunal in this case would in my view have been a suitable one for the appointment of an advocate to the court, though the decision would have lain with the Attorney General. The application of Article 15(c) to conditions in Iraq involved consideration of important issues of law and fact on which such an advocate could make a helpful contribution, in particular by testing the position taken by the Secretary of State on the law and its application to the materials before the tribunal. In addition, whilst an advocate to the court would not normally lead evidence, I take the view that he could properly have drawn the tribunal’s attention to, and made submissions on, relevant background material not otherwise before it.

This is certainly an interesting possibility. Back in 2005 I and others argued in an IAS pamphlet that a specially appointed court advocate would be useful in Country Guideline cases, for example to address evidence and issues not arising on the facts of the particular cases under consideration. However, Richards LJ is proposing such an advocate only where there is no advocate at all for the appellants.

The court’s conclusion is in fact not that ‘proper argument’ is a prerequisite in a country guidance case but that the tribunal erred in failing to do more to secure proper argument. It would appear that had UNHCR and the Attorney General both declined to provide some sort of submissions, the tribunal would have been entitled to do as it did.

The judgment ends by leaving the question open whether the tribunal might properly adopt an inquisitorial role and by quashing the CG case.

As the Court of Appeal once said in a previous case, all that time and learning was ‘desert air’.

SHARE