- BY Colin Yeo

Tribunal: nullified nullification no barrier to deprivation of British citizenship

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

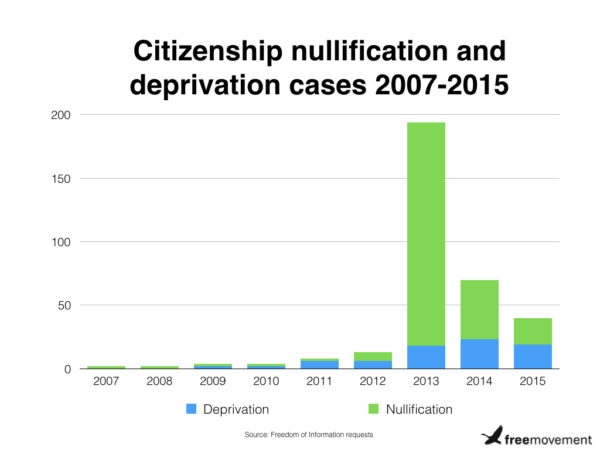

Taking away people’s citizenship became a popular pastime for Home Secretary Theresa May. After decades of the power being essentially taboo, associated as it was with Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, it was resurrected with a vengeance after 2010.

One way in which British citizens are stripped of their status is called citizenship “deprivation”, which is a process defined by statute and with the safeguard of an appeal provided by Parliament. Citizenship deprivation can be on grounds of public good, as in cases such as that of Shamima Begum, or on the basis that the person deceived the authorities in order to acquire citizenship. The person’s citizenship is recognised as having been granted but is then taken away again.

The other way is “nullification” which was previously an obscure common law process used in cases where someone pretended to be someone else in order falsely to claim citizenship. Where someone had falsely acquired citizenship in this way, the Secretary of State would simply declare that the person’s British citizenship was a nullity and had never truly existed; they never really had been British in the first place. There were no procedural safeguards and no right of appeal, although an application for judicial review could be pursued instead.

In a case called Hysaj [2017] UKSC 82, the Supreme Court held that the Home Office had been wrongly using the nullification process instead of the deprivation process. Essentially, the Supreme Court found that the vast majority of decisions to nullify British citizenship were unlawful. As a result, the Home Office went through its files and withdrew most of its nullification decisions. This meant that these people turned out still to be British citizens after all.

At least, for now. Would the Home Office now pursue deprivation action against them instead?

The answer, at least in some of the cases, is yes, as this latest version of the long running Hysaj litigation shows: Hysaj (Deprivation of Citizenship:Delay) Albania [2020] UKUT 128 (IAC).

Background

Mr Hysaj, having won in the Supreme Court, had his nullification decision withdrawn in February 2018. But a few months later, the Home Office issued a decision to deprive him of his British citizenship instead.

One can see why, when looking at the facts. Mr Hysaj, an Albanian national, arrived in the UK in 1998 aged 21 and claimed to be a 17-year-old refugee from Kosovo. Still using that false identity, he was recognised as a refugee and later acquired British citizenship. His lies unravelled when he sponsored his Albanian wife to join him in the UK and in 2008 the Home Office informed him that he was being considered for deprivation of citizenship.

In the meantime, this happened:

In June 2010 the appellant fell into a disagreement over a spilt pint with another man in a public house in Hemel Hempstead. Staff sent him out of the building into the beer garden to calm down. Having smoked a cigarette, he re-entered the building and, with a pint glass in his hand, tapped the shoulder of his victim, who turned around to receive the pint glass in his face, which shattered on impact. The victim sustained several cuts, including one that went all the way through his cheek and cut the back of his tongue. He required over forty stitches and was left with a degree of scarring. The appellant was convicted by a jury at St Albans’ Crown Court and on 20 May 2011 HHJ Catterson sentenced to him to five years’ imprisonment for wounding with intent to do grievous bodily harm and 12 months’ imprisonment for assault occasioning actual bodily harm, concurrent.

Paragraph 6

The relevance of this awful incident was, in strictly legal terms, questionable. It was unrelated to the deception or acquisition of British citizenship and deprivation action was not pursued in this case on public good grounds.

That said, it is hard to imagine that it was irrelevant to the desire of the Home Office to pursue deprivation action in this case. And it might well be relevant to what happens to Mr Hysaj if he is deprived of his British citizenship. In other deprivation cases, limited leave has apparently been granted, enabling the person to remain in Britain even if not as a British citizen. By contrast, one might guess that Mr Hysaj would probably face deportation action.

Mr Hysaj had also had three children, all of whom were, by virtue of his British citizenship, themselves British. As the Home Office originally elected to nullify Mr Hysaj’s citizenship rather than follow through on deprivation, this cast the status of the children into doubt: how could they have been born British if their father had never really been British at all? As we have seen, nullification transpired to be a legal dead-end, meaning that many years later Mr Hysaj was still a British citizen. But not for long.

Arguments

Resisting the decision to deprive Mr Hysaj of his British citizenship, his legal team argued in summary that:

- There has been massive delay since the original consideration of deprivation action back in 2008. It was “unfair and unreasonable” (and therefore unlawful) for the Home Office to follow that course now, so many years later.

- The Home Office had previously operated a general rule that citizenship deprivation action wouldn’t be pursued if the person had been resident in the UK for 14 years or more, and Mr Hysaj had a legitimate expectation that this policy would be applied in his case.

- Alternatively, the taking of a decision all these years later (after the 14 year policy had been rescinded in 2014) was an historic injustice and therefore unlawful.

- There was substantive unfairness in the case because Mr Hysaj could point to others in a very similar situation to his — i.e. they had pretended to be young Kosovans in order to get refugee status then citizenship — but who had been subject to deprivation action from the start, not nullification, and had therefore benefited from the 14 year policy.

- The Home Office should not be allowed to re-write the 14 year policy in order to take account of the appellant’s later criminal conviction.

- The later criminal conviction was not relevant to the decision to deprive the appellant of citizenship on the grounds of deception.

I have tried to parse these arguments from the determination, which might perhaps not fully or accurately restate the arguments actually made. The official headnote can stand as a summary of the tribunal’s response as well as one or two other points the Upper Tribunal’s reporting committee clearly wanted to emphasise:

1. The starting point in any consideration undertaken by the Secretary of State (“the respondent”) as to whether to deprive a person of British citizenship must be made by reference to the rules and policy in force at the time the decision is made. Rule of law values indicate that the respondent is entitled to take advice and act in light of the state of law and the circumstances known to her. The benefit of hindsight, post the Supreme Court judgment in R (Hysaj) v. Secretary of State for the Home Department [2017] UKSC 82, does not lessen the significant public interest in the deprivation of British citizenship acquired through fraud or deception.

2. No legitimate expectation arises that consideration as to whether or not to deprive citizenship is to be undertaken by the application of a historic policy that was in place prior to the judgment of the Supreme Court in Hysaj.

3. No historic injustice is capable of arising in circumstances where the respondent erroneously declared British citizenship to be a nullity, rather than seek to deprive under section 40(3) of the British Nationality Act 1981, as no prejudice arises because it is not possible to establish that a decision to deprive should have been taken under a specific policy within a specific period of time.

4. The respondent’s 14-year policy under her deprivation of citizenship policy, which was withdrawn on 20 August 2014, applied a continuous residence requirement that was broken by the imposition of a custodial sentence.

5. A refugee is to meet the requirement of article 1A(2) of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and a person cannot have enjoyed Convention status if recognition was consequent to an entirely false presentation as to a well-founded fear of persecution.

6. Upon deprivation of British citizenship, there is no automatic revival of previously held indefinite leave to remain status.

7. There is a heavy weight to be placed upon the public interest in maintaining the integrity of the system by which foreign nationals are naturalised and permitted to enjoy the benefits of British citizenship. Any effect on day-to-day life that may result from a person being deprived of British citizenship is a consequence of the that person’s fraud or deception and, without more, cannot tip the proportionality balance, so as to compel the respondent to grant a period of leave, whether short or otherwise.

Arguably one of the strongest points in Mr Hysaj’s favour, and a point of considerable general importance, is not mentioned in the headnote. This is the argument that the later criminal conviction was not relevant to the decision to deprive based on deception. This is barely addressed in the main determination either. All that Upper Tribunal Judge O’Callaghan says is that (paragraph 88):

With respect, that cannot be right. Such a consideration may legitimately inform her decision whether to invoke section 40(3).

He then goes on to address Article 8, a separate issue. With respect, these two very short sentences do not explain why the argument cannot be right or why it is legitimate for the Secretary of State, when excising a power based on deception, to consider subsequent unrelated facts. The statutory power is framed so that the Secretary of State “may” deprive “if” deception has been committed. On the face of it, exercise of the power is contingent on specified forms of deception. It is hard to see how anything else other than those forms of deception can be relevant to exercise of the power.

I imagine this may form a basis for an appeal to the Court of Appeal. Mr Hysaj may even find he joins the super-exclusive high fliers club of litigants who end up in the Supreme Court twice.

[ebook 57266]Alternatively, this may not help Mr Hysaj at all given that he admits the deception and in effect therefore that the power can be exercised. But the tribunal determination still does not address how or why the appellant’s subsequent conduct becomes relevant to whether the decision to deprive is the right decision.

Although it does not feature in the official headnote, the tribunal also considers the vexed issue of how far and in what way it is relevant to a deprivation appeal whether the appellant will be allowed to remain in the UK afterwards or not. The tribunal does reaffirm that previously held indefinite leave to remain is not resurrected but does not offer any real assistance on how judges go about considering the “reasonably foreseeable” consequences of deprivation, including whether the appellant will be forced to leave the UK, when the Home Office stays shtum about whether leave will be granted or not. I have a lot of sympathy here given this Gordian Knot is not a problem of this tribunal’s making.

Ultimately the appeal is dismissed and the decision to deprive Mr Hysaj of his British citizenship is upheld. Whether this is the end for Mr Hysaj remains to be seen.

SHARE