- BY nicknason

Tier 2: is it Brexit ready?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleTier 2 is a fortress.

Everything about the UK work permit system is designed to disincentivise employers importing migrant labour from outside of the EU.

Like a teacher who has lost control of her class at school and exacts revenge on her own children at home, who are occasionally fed and kept in the basement, the Tier 2 system controls what it can. For the time being, this does not include the number of workers who may enter to work from Europe.

At last count, 2.24 million European Economic Area (EEA) nationals are employed in the UK without let or hindrance, with no need to obtain permission from the Home Office to do so (except Croatian nationals), in the form of a permit or otherwise.

This article provides a brief overview of the way in which the Tier 2 system currently operates, and the obstacles placed in the paths of UK companies seeking to employ non-EEA national foreign labour. We consider the suggestion by the (pre-election) government that this system (or something like it) would be suitable to regulate the migration of skilled workers from the European Union in the event of a ‘hard’ Brexit.

Tier 2 Basics

The Home Office operates a sponsorship system where, if a UK-based company wishes to employ a non-EEA foreign worker, the employer must first apply for a sponsorship license. The Home Office website contains an overview of this process, and a riveting 205-page guidance document provides further details.

Step 1: applying for a license

In order to obtain a license, employers need to show, among many other requirements, they have systems in place to ‘monitor’ their employees, and are under a duty to inform the immigration authorities if a foreign worker is failing to comply with the terms of their visa.

This is now a standard part of the government’s socialised enforcement strategy, where immigration control (and its not insubstantial regulatory burden) is outsourced to third parties: to employers for employees, colleges and universities for students, and landlords for tenants. Notwithstanding the chastening endured in the election last week, this is likely to continue while the Conservatives hold office.

There are now two main types of Tier 2 licenses available for employers: one to facilitate inter-company transfers (Tier 2 (ICT)), and the other to bring in new non-EEA hires who do not already work for the business or entity wishing to bring them in (Tier 2 (General)).

Step 2: applying for Certificates of Sponsorship

Once granted a licence, an employer will be permitted to issue Certificates of Sponsorship to eligible non-EEA employees. Each individual employee will need a Certificate of Sponsorship in order to apply for a Tier 2 visa to travel to the UK and take up their post.

There are two types of certificate: restricted and unrestricted.

Employers can apply for unrestricted certificates for those workers who will be paid more than £159,600 per year, or if the prospective employee is already in the UK and will be switching into the Tier 2 (General) category, and in a few other limited scenarios.

ICT migrants are not counted within the quota, although existing employees wishing to transfer must meet additional criteria, including minimum salary requirements. As the name suggests, there is no limit on the number of foreign workers businesses can bring to the UK in these circumstances.

Negotiating the cap

Those companies who wish to employ foreign workers not meeting the unrestricted criteria, however, are limited in the number of certificates they can issue by the annual cap (currently 20,700 per year), split down into monthly allocations. In April 2017, for example, there were 2,200 certificates set aside for that month. The total number granted was 1,844 and the balance was carried over to the next month.

In the event that the monthly allocation is reached, certificates are awarded on a mini-points based system. Top points are awarded for jobs which are on the Shortage Occupation List, or which pay a high salary.

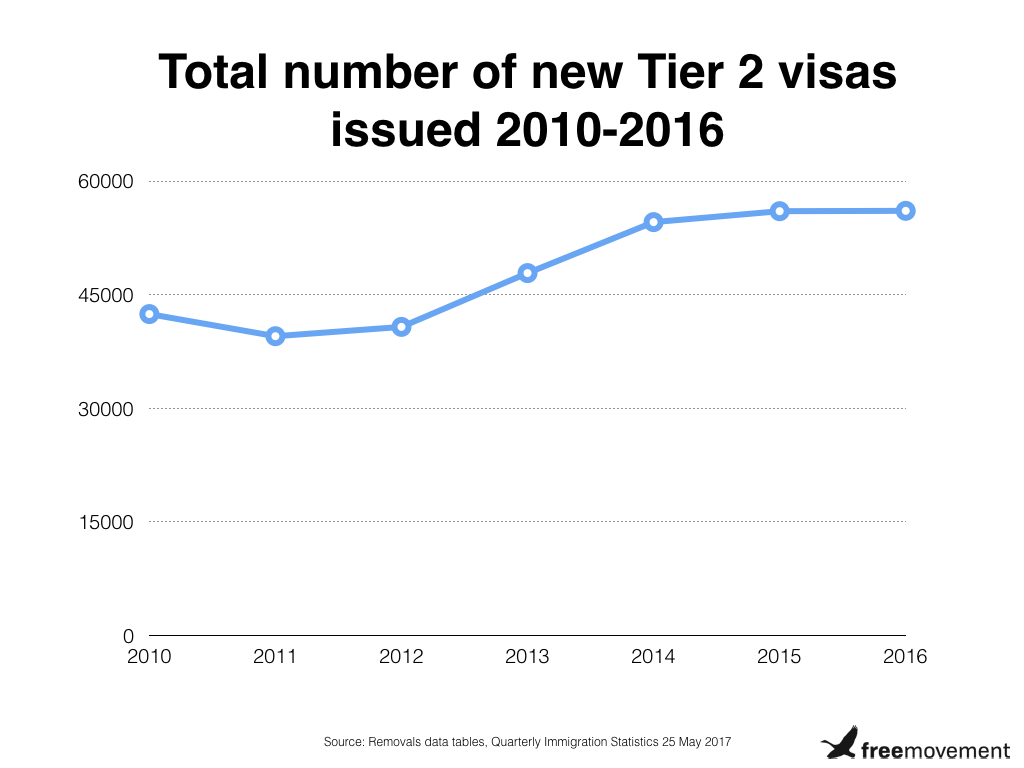

Apart from a run of monthly allocations in the summer and autumn of 2015, the applications made for certificates have not exceeded the number available since the introduction of the quota in 2011.

Once employees have been issued with the Certificate of Sponsorship, they can then apply for the visa which enables them to travel to the UK.

Obstacles for Employers

The overview of the Tier 2 system set out here omits much important detail, but even from a redacted description it is easy to understand why many businesses are reluctant to enter into this administrative vortex.

The British Chambers of Commerce said in evidence to the House of Lords European Union committee that the system was ‘riddled with complexity’. The Institute of Directors and others complain that it imposes significant burdens on business.

Indeed, it is no secret that the UK government has intended ‘to reduce demand for migrant labour and make sure British people have the right skills to fill jobs’. Leaving aside the fairly large question of whether the former intention will lead to the latter result, the government has been clear in its policy. We consider the levers which are being pulled to give it effect.

Annual Cap

The overall limit on the number of skilled workers permitted to enter the UK has been in place since 2011 and currently stands at 20,700. As mentioned above, this does not include dependents, workers applying with an offer of employment over a certain salary level, or existing employees looking to transfer to the UK via the ICT route.

In light of the existence of the free movement of European labour, and the numbers of Tier 2 workers who are exempt, the cap has always been a slightly curious notion, frustrated intention masquerading as policy. Like the Iraqi Information Minister insisting there were no Americans in Baghdad as the tanks rolled past in 2003, there were 93,244 Tier 2 work visas (including dependents, who are also permitted to work) granted in 2016.

Immigration Skills Charge

This is the latest and probably the most egregious example of the government’s attempts to reduce the importation of foreign labour. With all the subtlety of a Donald Trump early morning tweet, rules in effect from 6 April 2017 impose on larger employers (companies with more than 50 employees) a charge of £1000 per imported worker per year of their visa. Smaller companies are faced with a bill of £364 per employee per year.

The Conservative party made a commitment in its manifesto that this charge will double to £2000 per year. Whether this survives the political manoeuvrings of the coming weeks and months remains to be seen. But in the same manifesto promising that the UK ‘will be the world’s foremost champion of free trade’, an expensive tariff on foreign imports does not sit well with this lofty aim.

Other costs

Leaving aside the cost of the Immigration Skills Charge, separate Home Office fees must be paid to apply for a sponsor license, and for individual Certificates of Sponsorship. Managers responsible for human resources issues will have to spend significant amounts of additional time on the compliance requirements of their licenses, and learning how to navigate the Sponsor Management System (SMS), guidance, numerous appendices, 12 accompanying SMS manuals and Codes of Practice. Or the cost of a lawyer to do the same.

Employer penalties

The Home Office giveth, and it taketh away.

A sponsor’s license can be revoked for a number of reasons as listed in the Home Office guidance. This includes mandatory situations (the Home Office must revoke), for example where a sponsor employs a migrant in a job that does not meet the skill level requirements, or fails to properly undertake the Resident Market Labour Test (of which more below).

The Home Office also provides a long list of discretionary circumstances in which it may revoke a license. These include where an SMS User (a responsible person within the employer organisation who is assigned one of the SMS user roles) shares their password with someone else, paying a Tier 2 migrant in cash, or failing to comply with any sponsor duties as set out in the guidance.

Much like the stipulations prescribed to Nick the Greek by Rory Breaker in Lock Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, sponsors have to work very hard to ensure compliance.

Resident Market Labour Test

An employer will generally be required to carry out a Resident Labour Market Test (RLMT) before it can apply for a restricted Certificate of Sponsorship. This essentially means that, before offering the job to a non-EEA foreign worker, the employer must advertise the role in the UK and assess any candidates who apply for it in accordance with the relevant guidance. If there is no suitably-qualified or skilled settled worker available to take up the position, only then will the employer be permitted to bring in a foreign worker.

Upfront cost

The upfront cost of employing a skilled worker under Tier 2 on a five year visa, aside from compliance and administration costs, therefore works out as follows:

| Small employer | Large employer | Employee | |

| Sponsor licence | £536.00 | £1476.00 | |

| Certificate of sponsorship | £199.00 | £199.00 | |

| Immigration Skills Charge | £1820.00 | £5000.00 | |

| Initial application | £1174.00 | ||

| NHS surcharge | £1000.00 | ||

| Settlement | £2297.00 | ||

| Naturalisation | £1163.00 | ||

£2555.00 | £6675.00 | £5,634.00 |

As mentioned above, the Conservatives had planned on doubling the Immigration Skills Charge by 2020, leaving a large employer with a bill of £11,675 to obtain a license and bring one employee from overseas for 5 years.

Skilled workers in the UK

The system has been designed thus.

Rather than tumble down the rabbit hole of Tier 2 compliance, the government offers up a more attractive option of employing a ‘settled’ worker, free of the requirement to inform the border authorities if they fail to show up to work or the need to adhere to the many other rights and responsibilities prescribed in the guidance.

However, there is a central design flaw in this system. The full impact of the restrictions on the importation of foreign labour have never been felt, and have been cushioned by the existence of the large pool of EEA workers willing and able to fill gaps in the UK labour market. The UK has been entirely insulated from the full cost and complexity of this system whilst it has been a part of the European Union. By extension, the Tier 2 system has not yet been genuinely tested.

With unemployment currently running at 4.6%, the UK is currently close to what most economists describe as ‘full-employment’ (a definition which allows for the natural ebbs and flows of people changing jobs in a fast-moving economy). The UK employment rate – 74.8% – is also currently at its highest level since records began in 1971. In this context, it is easy to understand why certain sectors are facing severe difficulties recruiting for positions. In their Labour Market Outlook the Chartered Institute of Professional Development (CIPD) state that

the number of vacancies in the UK economy remains well above historical average levels. Just over half of surveyed employers that have vacancies report they are having difficulty filling them

Global Future reports that, in the construction industry, 66% of firms surveyed have turned away work due to staff shortages. The social care, farming and hospitality industries face similar issues. There are now as many as 40,000 nursing vacancies nationwide. According to that Global Future report, EU workers are thought to constitute 14% of workers in restaurants and hotels, 8.2% in construction and 10% of workers in transport. Although probably not a Tier 2 sector, the potential impact of labour gaps in agriculture – where 20% of all employees are reported to be foreign nationals, mainly from Bulgaria and Romania – on food security is alarming.

And who’s going to serve the Swedish Meatball Hot Wraps at Pret?

Is Tier 2 Brexit Ready?

The principle that ‘settled’ workers should be prioritised over foreign imports is unobjectionable, especially in the context of the government’s expressed desire to address the skills shortages which no doubt exist among the resident population. However, this prioritisation is based on – and feeds – the mistaken assumption that foreign workers are taking British jobs. Clearly, from the employment statistics recited above, nobody is taking British jobs, not even the British.

In evidence given to various parliamentary committees, business leaders were unanimously opposed to the use of the Tier 2 system (or anything like it) in any future immigration framework dealing with the migration of skilled workers, citing its complexity, cost and the additional regulatory burden for employers. Unsurprisingly, the government countered that the UK’s non-EEA immigration system was ‘very effective’, and that systems were working well, such that ‘it may be that some aspects of those non-EEA systems could be applicable to EU citizens’.

While the results of the recent election and a reduced mandate for a hard-Brexit provide a glimmer of hope to employers wishing to maintain access to the European labour market, the government will surely continue to argue that Tier 2 is a good starting point for a post-Brexit European skilled migrant framework, especially in light of its pledge to reduce net migration to under 100,000.

However, if free movement for EEA nationals is to cease, the weight of evidence suggests that if the new system is anything like the old, and the regulatory burden of operating a license remains, employers and businesses will be unable to fill vacancies and the recruitment crisis will deepen, with significant ramifications for the UK economy.