- BY Colin Yeo

Book review: The Windrush Betrayal by Amelia Gentleman

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

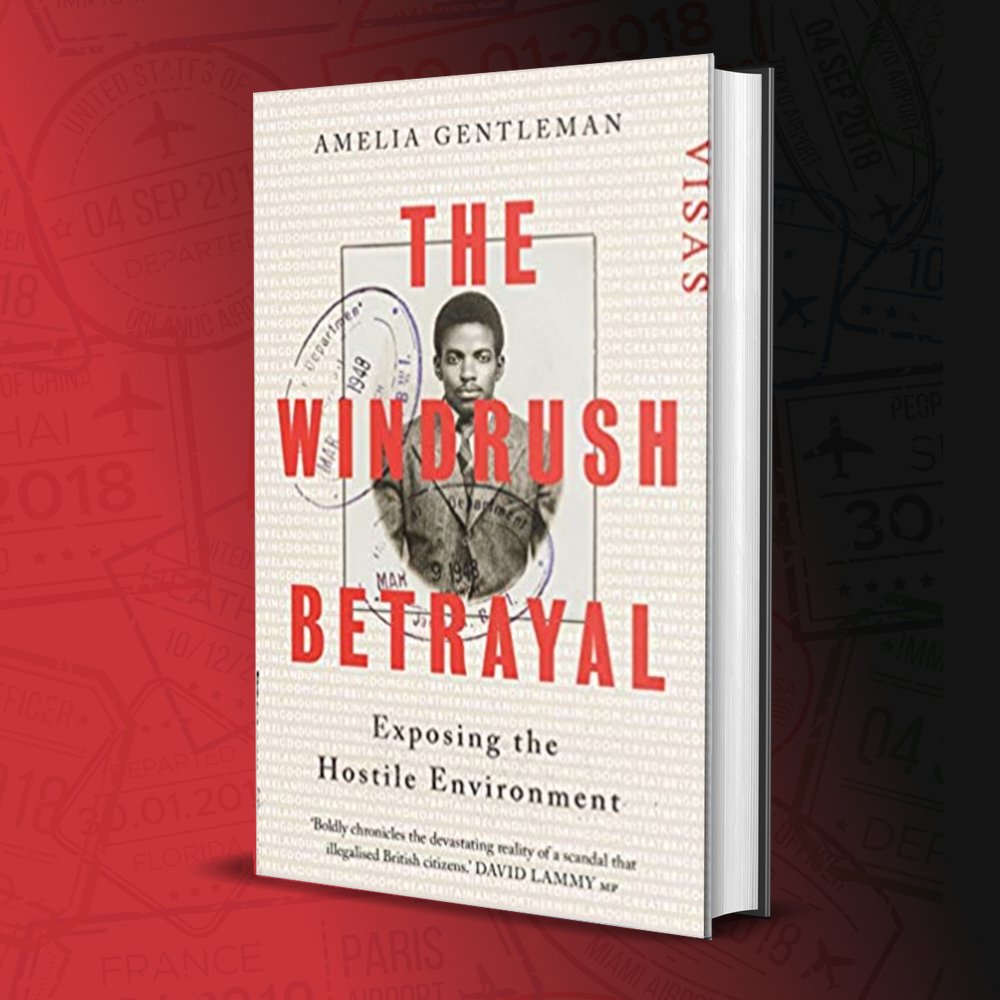

Amelia Gentleman will be familiar to Free Movement readers as the Guardian journalist who exposed what has become known as the Windrush scandal. Her account of what happened, how the scandal developed and why the Windrush generation experienced the problems they did should be compulsory reading for all Home Office ministers and civil servants. Immigration lawyers and campaigners also have much to learn.

You can order your own copy of Gentleman’s The Windrush Betrayal: Exposing The Hostile Environment here (affiliate link).

Gentleman writes brilliantly and her very readable book is full of moving portraits of the victims. It is a reminder that Gentleman’s ability to collect and then convey these very human and humane stories was absolutely critical to the exposure of the Windrush scandal. But this is only one element of the book, which sits alongside two other interwoven narratives.

Firstly, Gentleman describes the personal aspects: how she became involved in the first place, the doubts she faced about her role and function as a journalist, the lessons she learned about how government works (or not), the ongoing impact of institutional race discrimination, the personal challenges of working on such a high profile story while married to a government minister and a blow-by-blow account of the way the scandal unfolded. I found this fascinating, and was delighted finally to find out who coined the genius “Windrush generation” label that, to an alarming degree, transformed a story into a national scandal.

Secondly, she describes and explains the laws and policies that make up what we now call the ‘hostile environment’, the insidious system of citizen-on-citizen immigration checks. This is essential reading for policy makers and members of the public who want to understand what is going on. I was surprised, flattered and pleased to see one Colin Yeo being quoted a couple of times.

I confess this part of the book represents a personal challenge. I am currently working on a general interest book about the immigration system that covers a lot of the same ground, and Gentleman does a better job here than I ever could. I’m about 25,000 words in and I think I’ll need to rewrite quite a few of them!

Reading through The Windrush Betrayal, I found myself repeatedly wondering what has happened to the Windrush Lessons Learned Review commissioned from Wendy Williams. Gentleman describes fairly elderly residents who have faced some real difficulties in their lives, some of whom are not well educated, and who have not for various reasons managed to keep paperwork from years previously. They were living in the UK lawfully but were unable to prove it. Very similar problems are going to be faced by a swathe of EU citizens after Brexit because of the design of the EU Settlement Scheme. Not the white, well-educated French bankers, German engineers or Italian Phd students. But how about the Dutch Somalis, Lithuanian field workers, Polish meat processors, Slovak Roma or the post-war generation of now-elderly Europeans who moved here decades ago? And how about the currently undocumented children of all these groups?

One is left suspecting that the completed but unpublished Lessons Learned Review has already been buried, the Home Office has as an institution learned nothing from the Windrush scandal, and that the personnel at the top do not want to learn anything.

Gentleman’s work reminds us of the uncomfortable challenges posed by the Windrush scandal. I wondered then and I wonder now what more I could and should have done, both in case work and campaigning terms. The end of legal aid in immigration cases meant that victims were unable to access lawyers and the culture of refusal at the Home Office is not something that can be challenged by way of a legal case. Clearly, government is responsible, having introduced the policies and removed the effective means of challenge. Pro bono work by lawyers cannot fill the void left by ending legal aid. But what does it say about the immigration law sector, where many of us pride ourselves on our advocacy work and commitment, that so many victims were left suffering unknown?

More importantly, the book is a reminder that the UK’s immigration system is a disgrace, from root to branch, and it urgently needs major reform. The suffering of the Windrush generation was an inevitable and in many ways intentional result of the hostile environment, which is something that Gentleman, very much to her credit, fully recognises. The suffering of black people without documents was exactly what was supposed to happen, something that politicians like Amber Rudd still fail to realise. There remain many other iniquities in a system that treats migrants as a burden to be managed rather than as humans to be respected. The challenge is how to convince others that Windrush was not just a matter of bureaucratic oversight in an otherwise functional system.

Early in the book Gentleman describes the difficulties she faced getting lawyers to allow their clients to open up and speak to the media. We have in the past had good reason to be sceptical that media attention would be beneficial in immigration cases — it is very much a two-edged sword — but the fact is that media attention and the storytelling skill of good journalists was transformative of the immigration debate, starting with the difficulties faced by EU citizens and then moving on to the Windrush and other cases.

Just this week I and other experienced lawyers were surprised to see a fuss being made of the sole responsibility rule for children entering the UK. This is a long-standing rule that has caused serious problems for parents and children for literally decades. I saw it as an inevitable part of the legal landscape which might perhaps be mitigated by case law, rather than a blight that might be eradicated with a good campaign.

For me, the stories that Gentleman unearthed were routine and familiar. Many of my clients are already living in abject poverty and many of them face removal to a country they barely know. Immigration work is hard and in my way I am perhaps as case hardened and inured in the system as some Home Office officials. Case-by-case or even strategic legal challenges fail to address the monstrous unfairness of the present system, and perhaps even reinforce its legitimacy. If we are serious about reform we need a new approach, and new allies.

SHARE