- BY Sonia Lenegan

The Home Office is refusing Ukrainians’ protection claims and telling them to leave the UK

Table of Contents

ToggleRecently a Ukrainian national got in touch with me to raise concerns about mass refusals of asylum/humanitarian protection claims within the community. As I have been predicting for a while, he told me that many people have been driven into the asylum system through a fear of being forced to return to Ukraine and the lack of certainty regarding their long term future in the UK, in particular prompted by the exclusion of leave under the Ukrainian schemes from the long residence route.

He told me that many of these claims had recently been refused in what appeared to be standardised responses. The Home Office is telling people that they can return to the western regions of Ukraine and that they had 14 days to leave the UK or they would be removed, although their existing leave under Appendix Ukraine is not being cancelled.

I was put in contact with one person whose claim has been refused. His story is shared, with permission, below.

Once I started looking into it, it quickly became clear that the Home Office has indeed changed its position on the safety of Ukraine earlier this year and started refusing protection claims in much higher numbers than in previous years.

The data

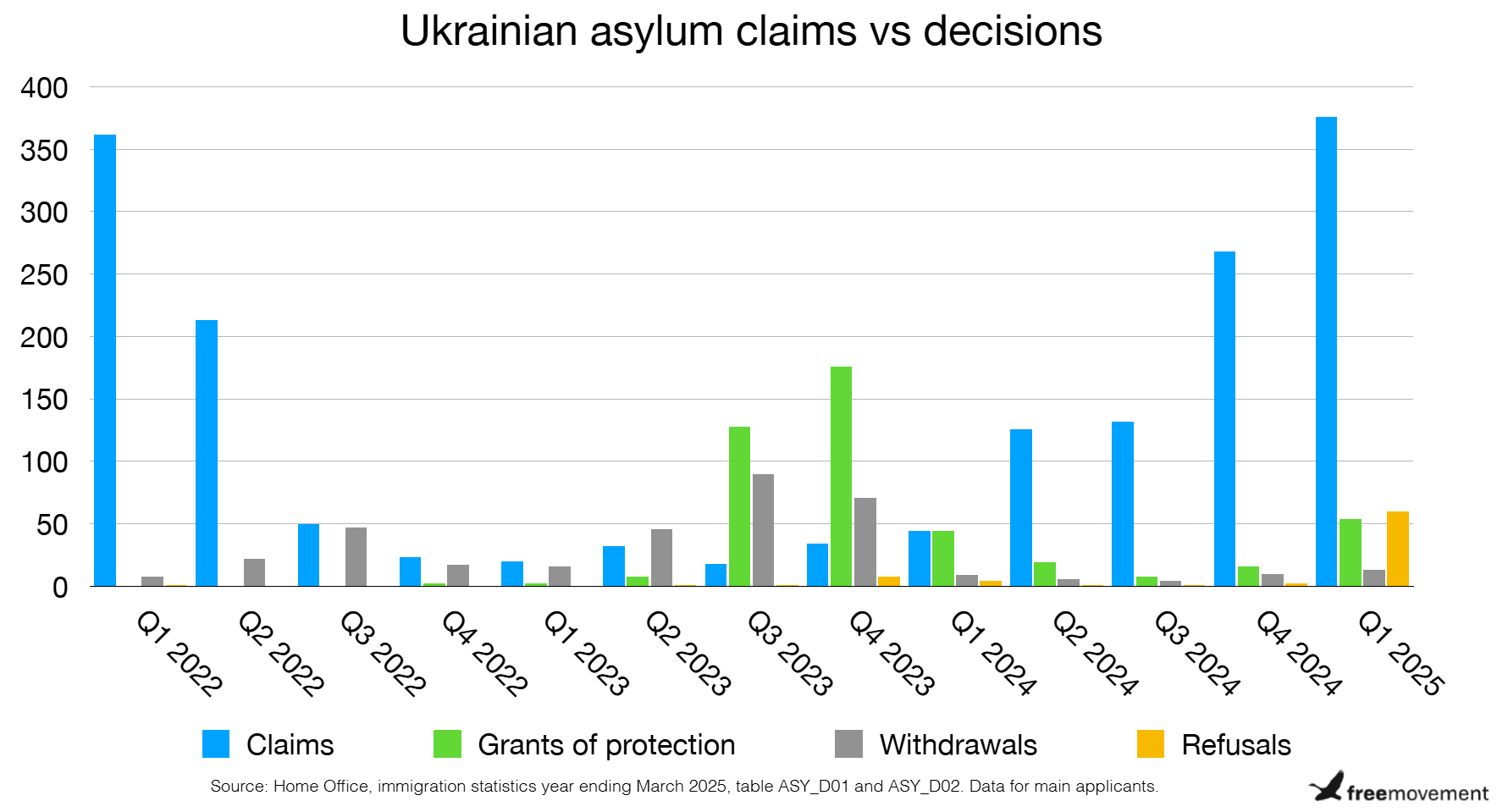

Since 2022, there have been 1,698 Ukrainian asylum claims by main applicants (representing 2,727 people once dependants are included). 902 of those have been made in the twelve months ending March 2025. There have been 436 claims granted humanitarian protection since the beginning of 2022 and 21 grants of refugee status. 359 claims have been withdrawn, 252 of those explictly withdrawn and the rest deemed withdrawn by the Home Office.

At the end of March 2025 there were 862 Ukrainian asylum claims waiting for a decision, 235 of those had been waiting for over six months.

There have only been 79 refusals in total since the beginning of 2022. However 60 of those refusals happened in the first three months of this year. The Home Office has obviously changed its position.

We can see from the below chart that although the number of claims remains relatively low compared to some other countries, more cases were refused than were granted in the first three months of this year. And it seems that the figure for April to June may be even higher once published, given the number of pending claims and the Home Office’s change of position.

Changes to the country policy and information notes

The obvious place to check for changes is the country policy and information notes. In January this year the Home Office published new guidance on the humanitarian situation as well as version 2.0 of its guidance “Ukraine: Security situation”. Both documents would no doubt benefit from a detailed review and analysis, but taking a brief look at the guidance on the humanitarian situations does raise some questions about what exactly people would be returning to at the moment.

The Home Office’s position is set out in the executive summary as:

In general, the humanitarian situation in Ukraine is not so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to torture or inhuman or degrading treatment as defined in paragraphs 339C and 339CA (iii) of the Immigration Rules/Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Humanitarian conditions across the country vary, with Kyiv and the western oblasts experiencing comparatively better conditions than areas near the front line, where challenges are more severe. However, overall, basic needs for food, water, hygiene, shelter, and heating are being met.

There is cause for concern about the safety and conditions of any return in many sections of the main body of the report. At paragraph 3.1.8 the report notes that in January 2025, there were an estimated 12.7 million people including 2 million children, in need of humanitarian assistance in Ukraine.

Because of a loss of housing stock from Russian attacks, in 2025 it is estimated that 6.9 million people or 18% of the population will require shelter and other assistance [para 3.1.9]. Food insecurity was projected to affect five million people in 2025 [para 3.1.11].

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ 2025 report noted [para 10.1.9]:

Ukraine’s economy in 2024 remains heavily impacted by the war, with businesses and livelihood activities badly affected, particularly in regions heavily reliant on agriculture and industry. Relentless airstrikes and artillery bombardments have devastated Ukraine’s industrial hubs in the eastern regions, rendering substantial parts of the country’s economic infrastructure inoperable. In urban areas, the collapse of local economies and insecurity have forced many businesses to close, in some cases temporarily, or reduce operations.

Paragraph 5.1.2 says that people can internally relocate within Ukraine, and suggests “Kyiv and the surrounding region or the western oblasts furthest from direct conflict, for example Chernivitsi, Zakarpattia, Ternopil, Rivne, Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv or Volyn that are, in general safe and offer more access to essential services and humanitarian support”. The position on Kyiv certainly seems unsustainable, I have not checked the other regions to see whether they are safe or if they even have the infrastructure to accept internally displaced people without them living in situations that may breach article 3.

It seems at least possible that country expert evidence independent of the Home Office may come to a different conclusion on the viability of these other locations as a safe option and what conditions internally displaced people would face if returned there.

Mykhailo’s* story

I lived in Kyiv all my life. On February 24, the full-scale war began and I was woken up by a series of explosions. Since then, Kyiv and the rest of Ukraine have been bombarded by drones, ballistic and cruise missiles.

There were several strikes near my home – the Russians were targeting the armored vehicle plant. I saw clouds of black smoke from my window after the explosions. Sleeping in Kyiv is very difficult – constant air raid sirens at night, bursts of automatic gunfire, explosions from air defense missiles and Russian rockets and drones.

When my wife and I were getting married, we were choosing a dress, and an air raid siren went off. We were just walking down the street, no one paid attention to the siren because it would sometimes sound ten times a day. But on that day we heard several very loud explosions overhead, and people began to scatter. I saw a few missiles and white trails in the sky from them. It was very loud. We hid in an underpass with other pedestrians.

One night, my wife and I were woken up by a loud rumble – I will never forget that sound – like a jet flying right overhead. It was a cruise missile. The next morning they showed a destroyed section of a multi-storey building. Two people died. I thank God it wasn’t my wife and me. Because of this, we were forced to leave Ukraine.

I arrived in the UK in September 2023 on a Homes for Ukraine visa, using a legal and safe route as required by British law, and I have been living in Scotland ever since. My wife arrived later; her Homes for Ukraine visa application took four and a half months to process, during which I contacted every humanitarian organisation I could, wrote to my MP, and called the Home Office hotline. The answer was always “wait.” During this time I spoke to many other Ukrainians who had waited eight months or even over a year.

In Ukraine, I worked as a doctor, but here, I cannot work as a doctor immediately, as I must go through a complex and lengthy process of diploma recognition, which takes a minimum of two to three years with no guarantee of success. So I am working as a support worker while studying at university. As you can see, I was forced to restart my career from scratch, even though I had already spent eight years studying medicine.

In November 2024, the UK government excluded Ukrainian visas from any route to indefinite leave to remain. I have had to start my life from a clean slate here, and if I am forced to leave, I will have to rebuild my life for the third time from scratch. I also do not feel safe returning to Ukraine, considering the constant shelling of our cities and the unwillingness to offer any real security guarantees for Ukraine. Russia has signed ceasefires before and then attacked again with even greater force — I do not want to live through another invasion.

I decided to apply for humanitarian protection. This route is for those not persecuted by the government, but for whom it is still unsafe to return to their country. In December 2024, I submitted my application, and that same month I had my first interview. It was purely formal – my name, where I’m from, why I’m seeking asylum.

The second interview took place in May 2025. On that day, the Russians bombed Kyiv again – two people were killed and seven injured. In April 2025 alone, 15 people died in Kyiv and 102 were injured. Anyone who goes to sleep may not wake up the next day or may wake under rubble. I was extremely anxious.

The last time I felt that anxious was during an exam at medical university. As it turned out, my anxiety was not unfounded. The interview was really more like an interrogation. A very unpleasant experience. The interview lasted two and a half hours.

One and a half weeks later, I received a letter from the Home Office. They had refused to grant me humanitarian protection and told me to leave the United Kingdom, or face forced deportation to Lviv or Kyiv.

It’s hard to describe how I felt when my claim was refused – especially since Ukrainians are called “refugees” by every news outlet. I was denied because the western regions of Ukraine are considered “safe,” even though that claim doesn’t reflect reality – missiles also strike there, and there are no guarantees I won’t be killed.

Russian missiles have the range to strike any city in Ukraine, and there are not enough air defense missiles or launchers. Even if a Russian missile or drone is shot down, it doesn’t protect people from shrapnel. People are constantly killed because of this.

Another reason I was refused is because I didn’t apply for asylum in Poland or Dublin on my way to the UK. I have never been to Dublin. I clearly stated my route – from Gdańsk to Glasgow – and it is documented in the interview transcript. I think the Home Office worker simply copied it from a previous applicant’s case.

I spoke with my lawyer, and she told me that almost all Ukrainian applications are currently being rejected. That same day, I contacted another lawyer, and got a similar answer – many rejections – but they said they would see whether in my case it’s worth submitting an appeal. I personally know another Ukrainian who ended up in the same situation as me.

Despite all the hardships, I want to thank the people and government of the United Kingdom for what they have done for my country, my people, me, and my family. Overall, I’m glad that I had the opportunity to tell my story.

Conclusion

People in the UK with leave under Appendix Ukraine are currently safe but they are certainly not secure. Short term visas make it more difficult for people to get jobs and to rent property, and displaced Ukrainians are more than twice as likely as the general population to experience homelessness.

The situation in Ukraine remains dangerous in many parts and very unstable, as seen with the position in Kyiv. The government’s position can be compared to that taken on Syria or Afghanistan recently, where protection claims are either not processed or are refused, despite the facts arguably not supporting that position.

The problem, as ever, will be with challenging these refusals. Many of the applicants are unlikely to be eligible for legal aid, because they are working. Private asylum work, in particular appeals, is expensive and given the Home Office (sensibly) does not seem to be taking any decisions to cancel the leave already held by the Ukrainians (although the letters do, inappropriately, tell them to leave the UK within two weeks), there is less of an incentive to pursue this option.

There are certainly no easy answers here, Ukraine’s position that it wants its nationals to return and rebuild once it is safe again is completely understandable and I am sure that many people will want to do so. But the desire for stability by people who are here is also understandable. We have no idea how and when a return to Ukraine will be possible, and in the meantime the situation for Ukrainians like Mykhailo in the UK remains difficult and uncertain.

*Name has been changed

SHARE