- BY CJ McKinney

National security court slams immigration lawyers

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The secretive court that hears immigration and nationality cases with a national security element has hit out at lawyers for failing to follow its rules.

A Special Immigration Appeals Commission practice note, published on 4 December, slams the work of immigration lawyers in national security cases as at times “unacceptable”. SIAC complains of a rise in the number of late and “improperly instituted” appeals, and warns that judges may start to demand more evidence that solicitors are actually acting in accordance with their clients’ wishes.

Decisions to strip someone of their British citizenship or right to live in the UK will be certified as suitable for SIAC if the evidence against them is considered too sensitive for open court. It allows for “closed” evidence that cannot be seen by the person concerned or their lawyer.

Anita Vasisht of Wilson Solicitors, who has handled many SIAC cases, told Free Movement that “we all respect the need to observe procedures. However, in view of the very significant challenges faced by this particular group of appellants who are already enormously disadvantaged because of the nature of the SIAC process, we have to hope that SIAC will consider applications to accept late or improperly instituted appeals with the utmost sympathy”.

“No excuse” for sloppy paperwork

The note opens by complaining that SIAC “has been receiving increasing numbers of late appeals and improperly instituted appeals”. The approach of lawyers to late appeals is said to be “variable and, in some cases, unacceptable”.

It goes on to reiterate the time limits within which appeals to SIAC have to be taken and reminds appellants that they are “not entitled to an extension of time if they lodge an appeal late”. Extensions will only be granted where “by reason of special circumstances, it would be unjust not to extend time”.

SIAC also complains that “it is the responsibility of appellants’ representatives to fill in the notice of appeal accurately and completely”, including relevant dates. “There is”, the note scolds, “no excuse for leaving these boxes blank”.

Applications for an extension must be accompanied by a signed and dated witness statement. The quality of these also comes in for criticism: “it is not acceptable for events to be recounted in a random order, because this makes it difficult for the Commission to understand, without unnecessary extra work, what has happened and whether there are special circumstances”.

The note threatens that “unexplained gaps in the sequence of events may cause the Commission to doubt the frankness of any explanation and/or, whether there are special circumstances which would justify an extension of time”.

Doubts about clients’ instructions

Many SIAC cases involve clients who are abroad and accused of involvement in or connection to terrorism — such as “ISIS bride” Shamima Begum. Some, like London-born student Ashraf Islam, end up in foreign prisons. This can make it difficult for lawyers trying to resist punitive action to stay in consistent contact with their clients and take instructions on their appeal.

According to Vasisht, this is no accident.

In every one of our citizenship deprivation cases, the SSHD served the decision when our client was outside of the UK. In a number of those cases, it’s clear the SSHD deliberately waited for our client to leave before, almost instantly, sending plain clothed police officers to serve the decision on their family members: in one case, an elderly, widowed mother in ill health; and, in another, a vulnerable wife with no English whose young child had to read and attempt to interpret the contents of the letter to her – the letter that says we think dad is a threat to national security.

The SIAC practice note raises doubts about whether lawyers are acting on their clients’ instructions in such circumstances — even where the solicitor has certified that to be the case. It says that

there is an increasing trend for appeals to be lodged in circumstances where there is at least a doubt whether the appeal has been lodged in accordance with an appellant’s instructions, for example where an appellant is detained abroad, and there is limited, or no evidence, that he knows about the decision in question and/or has given any instructions to challenge it.

The note goes on to say that SIAC has “concerns” about this trend but does not want to impose “undue obligations on solicitors”.

The certificate is prima facie evidence that the solicitor concerned has such instructions. The Commission may, nevertheless, in cases in which it doubts whether the appellant has given his authority, require further evidence of that authority to be provided. It will consider any representations GLD wishes to make. The Commission reminds solicitors doing this work that they must not sign such a certificate unless they have express instructions from the appellant, or from a person who, to their knowledge, has the appellant’s authority to give such instructions.

Free Movement understands that SIAC had originally intended to require sworn witness statements from solicitors whenever they were lodging appeals on behalf of clients detained abroad. But, as the extract above shows, the final version of the note does not go that far.

Rise in deprivation of citizenship cases

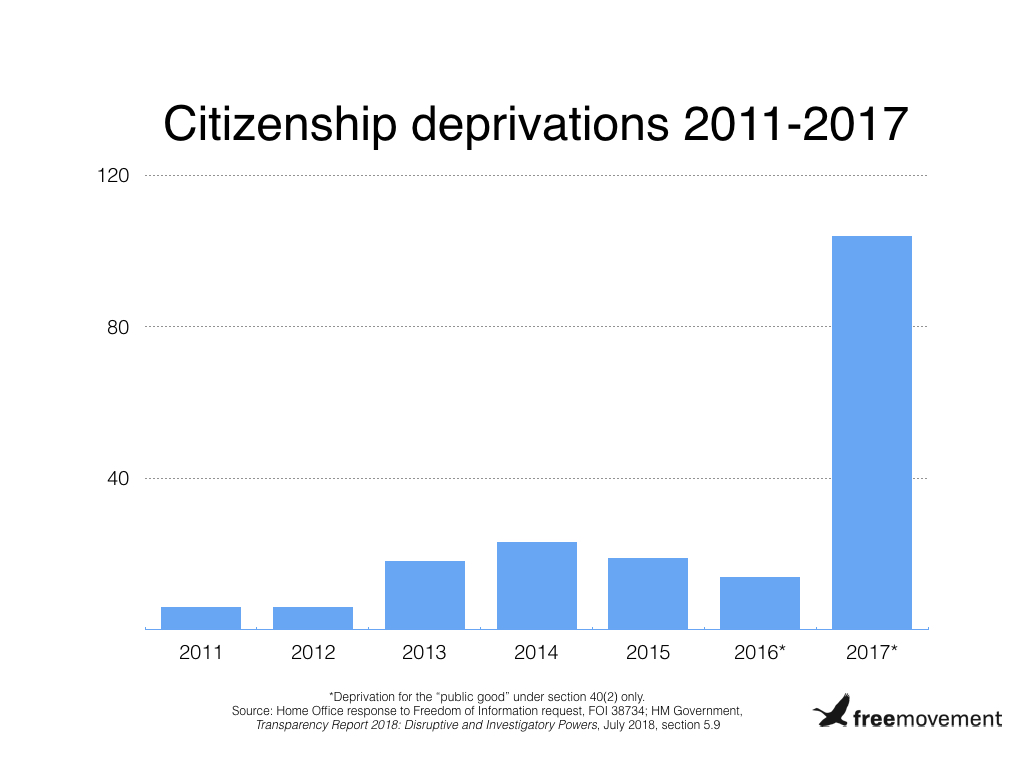

The backdrop to the note is a sharp rise in the number of people stripped of their British citizenship on national security grounds. In 2017, the Home Secretary decided that it was “conducive to the public good” to deprive 104 people of their British citizenship. That was more than the previous six years combined, and means many more potential cases for SIAC.

That trend may well have continued since 2017, although the Home Office has not released the supposedly annual statistics on deprivation of citizenship since July 2018.

At all events, the spike in the number of deprivation cases seems to have brought lawyers lacking knowledge of SIAC procedures into contact with the court. One practitioner told Free Movement that the note was likely to be aimed at less experienced practitioners who are used to the relative informality of the immigration tribunals.

Vasisht added that “realistically, we have to accept that SIAC needs appellants’ representatives to follow procedures. If some of our colleagues are not doing that, then good there’s a practice note to instigate order where else there may be chaos”.

One Response

Whilst it seems that SIAC is being somewhat heavy-handed in expressing their concerns, I’m finding it difficult to quantify the number of SIAC deprivation appeals actually in the system at present. My understanding is that whilst not EVERY s40 (2) decision ends up in SIAC, every deprivation decision in SIAC is (largely) predicated on s 40 (2) BNA 1981. Connor, are you able to shed any additional light on this matter?