- BY Ayesha Riaz

Shamima Begum, legal aid and access to justice

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

On 19 July 2020, Boris Johnson announced that the government would review legal aid rules in light of a Court of Appeal judgment requiring the government to repatriate a young woman, Shamima Begum, whom it had deprived of British citizenship on the basis of her assistance to ISIS in Syria. The Prime Minister stated: “it seems to me to be at least odd and perverse that somebody can be entitled to legal aid when they are not only outside the country, but have had their citizenship deprived for the protection of national security”.

This blog looks at how the Prime Minister’s response, surprising as it is, fits into government policy on legal aid over the past decade.

Background

On 17 February 2015, a 15-year-old British schoolgirl, Ms Begum, and two of her friends travelled to Syria via Turkey. They were recruited by ISIS agents as brides for foreign fighters. A few days after arriving in Raqqa, Syria, Ms Begum married a young Dutch convert to Islam and foreign fighter for ISIS. She had three children after arriving in Syria, all of whom died there.

The Telegraph has branded Ms Begum as an “enforcer” who allegedly sewed suicide vests onto her fellow jihadis. In February 2019, the Home Secretary wrote to Ms Begum’s family informing them that he had made an order stripping her of her British citizenship on the basis that she is a national security risk.

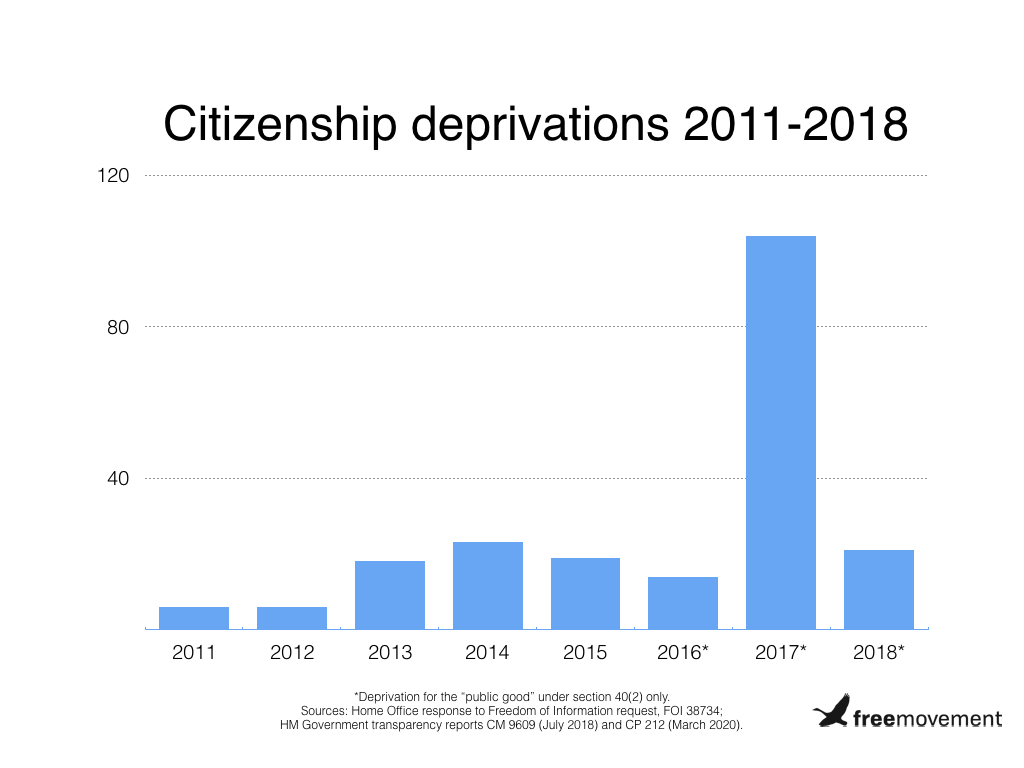

The British Nationality Act 1981 provides that a person can be deprived of their citizenship if the Home Secretary is satisfied it would be “conducive to the public good” and that person would not become stateless. In recent years, there has been an increase in deprivation orders made against those involved in terrorism and extremist activity.

Challenging deprivation of citizenship

Challenges to deprivation of citizenship on terror-related grounds are heard in the Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC). Ms Begum exercised her appeal rights and, in a preliminary ruling, SIAC held that deprivation of British citizenship would not render her stateless as she holds Bangladeshi citizenship through her parents. The Bangladeshi government, however, “asserts that Ms. Shamima Begum is not a Bangladeshi citizen” and says “there is no question of her being allowed to enter into Bangladesh”.

Ms Begum also applied for “leave to enter” the UK (a route only applicable to those who are not British citizens). That application was refused and Ms Begum challenged that refusal up to the Court of Appeal. She argued that she could not mount a “fair and effective” challenge against deprivation of citizenship from abroad, and further that she was at risk of death or inhuman treatment contrary to Articles 2 and 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights if she was not permitted to return to the UK.

The Court of Appeal handed down its decision in favour of Ms Begum on 16 July 2020. The government’s application for permission to appeal further was granted on 31 July 2020, and her case will now be heard by the Supreme Court.

Ms Begum’s case is being pursued by Birnberg Peirce solicitors and funded by legal aid, as the young woman has no resources of her own to pay for legal assistance and representation.

A brief history of legal aid

Universal means-tested legal aid was introduced by the Legal Aid and Advice Act 1949 to ensure that access to justice was not denied to the poor. The system has gone through numerous revisions and has not always been considered a solution to unmet legal needs.

The percentage of households that were eligible for legal aid stood at 80% when the scheme was introduced in 1949, but this fell to 47% between 1994 and 1995 and has since fallen further. As the means test stopped more and more people from receiving free legal advice and assistance, in the 1960s, alternative mechanisms were established, such as Citizens Advice Bureaux and law centres that were restricted by catchment area and funded mainly by local authorities. But this funding was dependent on the willingness and capacity of local authorities to support this work and legal aid continued to be a very important component of the provision of legal services to the poor.

In the 1990s, the system went through substantial change with the concentration of legal aid to a limited number of providers based on a complex franchising system where law firms were invited to tender for contracts. Immigration and asylum was one of the first sectors subject to the franchising system. Hourly rates of pay were not increased and the payment system moved increasingly to fixed fees for defined tasks. The result was that advisers had to do ever-increasing amounts of work for lower payments.

A huge shake-up of the legal aid system occurred in 2012 with the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, which sought to cut costs by further limiting access to legal aid. Instead of the usual way of limiting access, by reducing the financial limit under which people have access to legal aid (or failing to adjust the limit to account for inflation or changes in average incomes in the UK), a new approach was adopted: excluding people from legal aid on a sectoral basis.

Amongst the sectors excluded completely from legal aid irrespective of people’s means was much of immigration law. Most categories of immigration were simply excluded from the scope of legal aid altogether, with exceptions for asylum based on the UK’s international commitments.

By 2014, the government was considering ways to limit legal aid even further to reduce the number of immigration appeals with particular reference to the higher courts. New limitations were included in the Immigration Act 2014 to this effect.

The move from a universal system based on resources to a sectoral one excluding foreigners/migrants was a profound shift towards a more xenophobic approach to public policy which found its most developed form in the “hostile environment“.

Legal aid in citizenship deprivation cases

Proceedings before SIAC are still in scope for legal aid under the 2012 Act. The justification was “the importance of the issues considered by SIAC – the removal or exclusion of an individual from the United Kingdom on national security or other public interest [grounds]”, according to a government consultation paper laying the groundwork for the 2012 changes.

The government also admitted in the consultation paper that SIAC cases are not among the ones that litigants could resolve themselves, given that litigants may not be able to see all the evidence against them, and that it would be difficult to access alternative funding. In any event, anyone who applies for legal aid funding for SIAC cases is subject to “strict eligibility tests” (again in the government’s own words).

Targetting foreigners for legal aid cuts

Nevertheless, the Johnson government’s view that Ms Begum and people like her should be excluded from legal aid follows the logic of the modern legal aid system. She is, in the government’s eyes, no longer a British citizen but a foreigner — and the objective of the Immigration Act 2014 was to reduce access to justice for non-British citizens so they would not be able to appeal against Home Office decisions about their status. As Ms Begum was transformed by the Home Office’s action from a citizen into a foreigner, so she too, from the government’s standpoint, should not be legally aided to challenge that decision.

The government’s hostility to legal challenges by non-British citizens is part of a continuum which began in the 1990s. The principle set out in the 1949 Act — that justice should be equally available to the poor and the rich — has been fundamentally abandoned. While ousting the jurisdiction of the higher courts to consider immigration cases was unsuccessful, depriving applicants of access to justice through denial of legal aid has become the substitute. The fact that discriminating against people seeking access to justice on grounds of their immigration status is inconsistent with the foundations of the legal aid scheme has not deterred governments from seeking to insulate their decisions from judicial scrutiny.

The recent approach as enunciated by the Prime Minister is even more egregious. Here is someone exercising their right to challenge the removal of their British citizenship, but the objective is to prevent them from doing so by excluding them, or others in the same situation in future, from legal aid. If the government acts on the Prime Minister’s proposals, Parliament should reject this discriminatory approach to ensure equality of arms. If Parliament is unequal to the task, it will be for the courts to protect the scope of their powers.

This article was co-authored with Professor Elspeth Guild.