- BY colinyeo

Could Catalan separatists qualify for refugee status in the UK?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleCarles Puigdemont, erstwhile President de la Generalitat de Catalunya, fled Spain to Belgium this week following his parliament’s unilateral declaration of independence for Catalonia. Several of his ministers followed him into exile. A European Arrest Warrant will soon be issued seeking their extradition back to Spain to face criminal charges.

Meanwhile, eight other Catalan ministers who stood their ground were detained yesterday by Spain’s high court and face charges of rebellion, sedition and misuse of public funds for their roles in the independence referendum, which was illegal under Spanish law. Other senior Catalan politicians face similar charges but their cases are complicated by parliamentary immunity.

Puigdemont and his ministers breached Spanish law. But is this a case of prosecution or persecution? Might the Catalan separatists have good claims to be political refugees? Or are they instead fugitives from the criminal justice system of a mature democracy with a legitimate system of laws and plentiful safeguards for fair trials?

What is a refugee anyway?

A refugee is defined in the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees 1951 as a person with a well founded fear of being persecuted by reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion and who cannot avail him or herself of the protection of the home country.

We cover the legal definition of “refugee” in more detail in this previous blog post:

The critical legal issues for the Catalan separatists would be:

- Does being prosecuted amount to being persecuted?

- Is the prosecution because of political opinion or enforcement of a legitimate criminal law?

- What punishment might they face if convicted?

- Is there generally protection from persecution available in their home country, i.e. is it a functioning democracy under the rule of law?

There is an added dimension which is relevant to Brexit: EU law mandates that EU countries must be regarded as safe countries. This makes it virtually impossible for an EU citizen successfully to claim asylum in another EU country. After Brexit, however, the UK could potentially become a safe haven for EU citizens seeking asylum.

Prosecution vs persecution

[ebook 17797]One man’s fugitive is another man’s hero. Distinguishing between legitimate prosecution and illegitimate persecution has always been controversial. This has always been an issue in refugee law.

Where a political activist delivers leaflets in the street in breach of a national law and is then arrested, sentenced and fined, does this amount to being persecuted for reasons of the activist’s political opinion? Or is it not for the asylum state to question the national laws of other countries?

What if that country has recently emerged from civil war or is in a state of emergency and a law preventing political campaigning is considered necessary there? What if the political party is linked to a terrorist organisation? What if, instead of a fine, the activist would be imprisoned for three years? What if the prison conditions are life threatening? What is the criminal offence was, instead of delivering leaflets, being homosexual or being Christian?

What if the offence was unilaterally declaring independence on the basis of a referendum that was illegal under Spanish and Catalan law and in which turnout was 43%?

In refugee law, the distinction between prosecution and persecution is usually drawn with reference to international legal standards. If the criminal offence is one which is generally considered legitimate by international standards and the punishment is appears broadly proportionate then this will be considered prosecution.

EU law, in the form of Directive 2004/83, known to refugee lawyers as “the Qualification Directive”, sums these issues up rather pithily by including at Article 9(2) the following example of an act of persecution:

prosecution or punishment, which is disproportionate or discriminatory.

Could Puigdemont claim asylum in the UK?

Mr Puigdemont’s tragi-comic disappearance, initially to Belgium, led to speculation that he might claim asylum in that country. That is legally possible in Belgian law, according to the Financial Times. But this blog is not concerned with Belgian law. For us the more interesting question is: could Mr Puidgemont, following in the footsteps of famous political refugees from Louis Philippe to Karl Marx, claim asylum in Britain?

The short answer is “yes” he could make a claim. But the chances of such a claim succeeding would be zero.

First of all, Schedule 3 of the inelegantly named Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants, etc.) Act 2004 sets out lists of safe countries for the purpose of determining asylum and human rights claims. The first of these lists is a list of EU member states, which of course includes Spain. Spain is therefore a country which the Act mandates must be treated by “any person, tribunal or court” as one

where a person’s life and liberty are not threatened by reason of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion (schedule 3, para 3(2)(a)).

The Act goes on to provide that if an EU citizen does make an asylum claim — which we can see would be doomed to fail — then the Home Office can send that person home despite that asylum claim being made (schedule 3, para 4). The Home Office can also prevent a person lodging an appeal against any refusal (schedule 3, para 5).

This means that according to an Act of Parliament any asylum claim by an EU citizen is ultimately doomed to fail. However, the Act does not prevent an EU citizen from making the claim in the first place, even if it will ultimately fail.

Instead, preventing EU citizens even making an asylum claim is accomplished by the Immigration Rules, the day-to-day reference point for immigration officials and lawyers. The rules say as follows:

326E. An EU asylum application will be declared inadmissible and will not be considered unless the requirement in paragraph 326F is met.

326F. An EU asylum application will only be admissible if the applicant satisfies the Secretary of State that there are exceptional circumstances which require the application to be admitted for full consideration.

This presumption of inadmissibility was introduced in November 2015. It is also reflected in Home Office guidance documents, as we reported at the time. The examples given of circumstances that might be considered exceptional are limited to circumstances where the sending country has derogated from the European Convention on Human Rights or is in formal trouble under Article 7 TEU for breach of human rights.

Despite these significant obstacles, a couple of hundred EU citizens have been applying for asylum in the UK in recent years, including a handful of Spanish citizens in 2015. Vanishingly few — at most 40, some of whom were from Croatia just before Croatia joined the EU — have been successful.

EU law can prevent asylum claims within the bloc

The reason that the UK treats EU countries as automatically safe for the purposes of asylum claims lies in EU law. Protocol 24 to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union declares that

Member States shall be regarded as constituting safe countries of origin in respect of each other for all legal and practical purposes in relation to asylum matters.

There are some exceptional cases permitted under that protocol, including a general power for an EU member to go ahead and consider any application it wants, although it is narrowly drawn:

if a Member State should so decide unilaterally in respect of the application of a national of another Member State; in that case the Council shall be immediately informed; the application shall be dealt with on the basis of the presumption that it is manifestly unfounded without affecting in any way, whatever the cases may be, the decision-making power of the Member State.

We can see that the UK has implemented this aspect of EU law. But what happens after the UK leaves the EU?

Will Brexit mean that EU citizens can claim asylum in the UK?

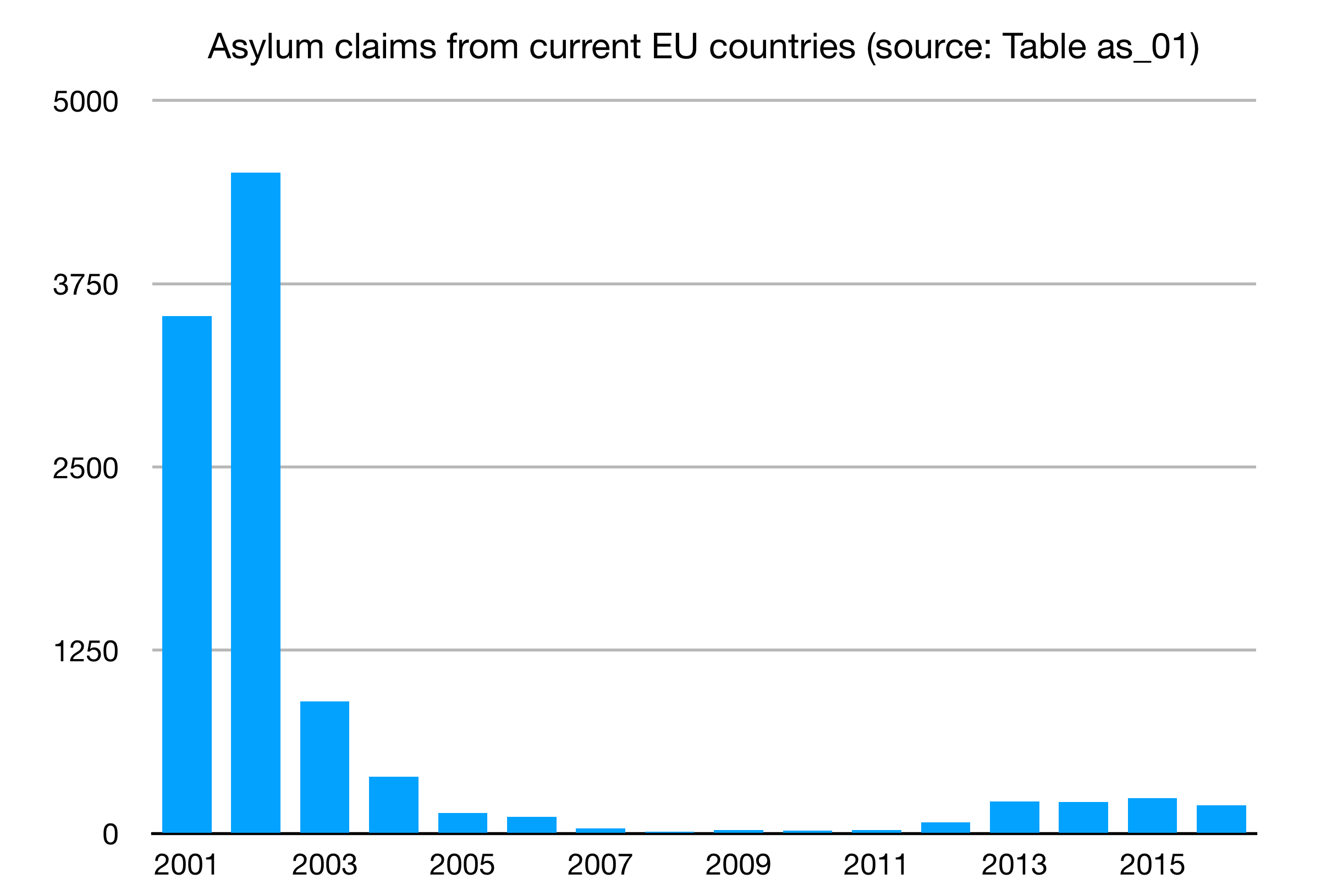

Although very few EU citizens have been claiming asylum in the UK in recent years, that wasn’t always the case. In the early 2000s, the UK did grant asylum to several hundred (mainly Romanian) citizens of now-EU nations.

With Brexit, the EU law prohibition on considering such claims falls away. There will be no insuperable barrier to Catalan nationalists or Romanian Roma pursuing an asylum claim in Britain, although the decision in Horvath v Secretary of State For The Home Department [2000] UKHL 37 will make it difficult for such claims to succeed.

“Taking back control”, then, could mean taking back responsibility for processing thousands of asylum claims by EU citizens.