- BY Samar Shams

Power to close down businesses employing illegal workers goes virtually unused

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The Immigration Act 2016 authorises immigration officers to temporarily close down businesses persistently employing illegal workers. The provision is one of several that make up the hostile environment policy, which has been rebranded the “compliant environment”. The objective of the policy is to encourage those without permission to live and work in the UK to depart voluntarily.

Illegal working closure notices

Under Schedule 6 of the Immigration Act 2016, a high-ranking immigration officer may prohibit access to a business’s premises if it is employing an illegal worker and its history includes an illegal working offence or an order to pay an illegal working penalty within the last three years, or it has failed to pay an illegal working penalty. The officer displays the notice on the door to the premises.

The business can remain closed for up to 48 hours, by which time the immigration officer must have applied to the court for an illegal working compliance order. The court’s order can prohibit access to the premises for up to 12 months or require that the business carry out right to work checks at specific times.

How are closure notices being used?

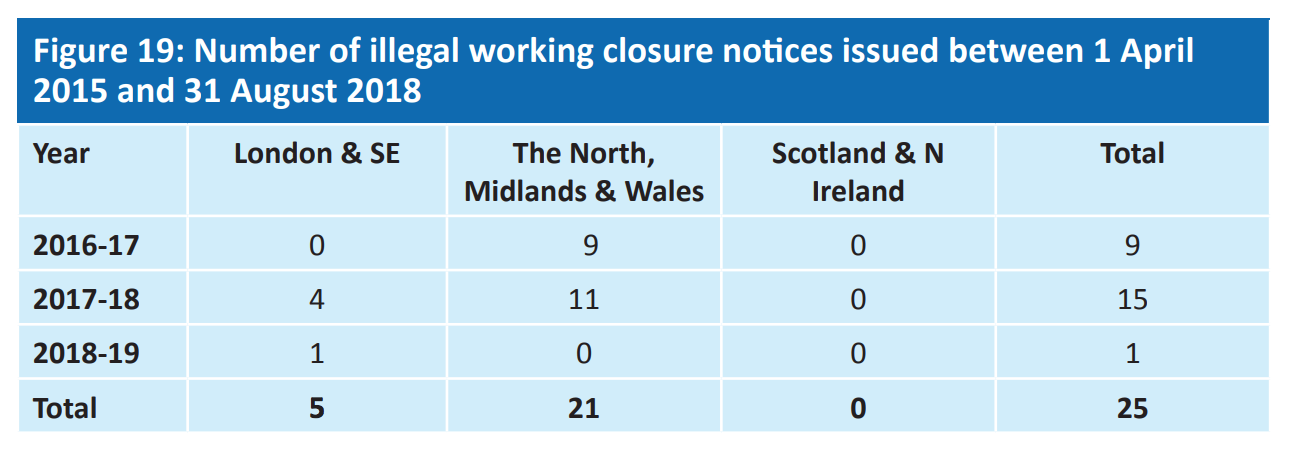

The Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration assessed the Home Office’s use of illegal working closure notices in a report published in May 2019. The Chief Inspector found that the power has not been used much, as reflected in this table from the report:

Immigration officers reported that they do not issue illegal working closure notices because the process is too resource-intensive. A visit to court is required as well as follow-up visits to the business premises. It is possible that no illegal working closure notices have resulted in a court ordering a premises to remain closed for longer than the initial 48 hours. One illegal working compliance order reported in the media imposed various conditions on the business concerned, but allowed it to reopen.

The data reflects a general reduction in immigration enforcement activity after the Windrush scandal came to light. According to the Chief Inspector’s report, Windrush “fundamentally altered the environment in which [immigration enforcement] operated”. Across government, the appetite for enforcement was reduced. Some businesses were hostile towards visiting officers, recruitment became more difficult and other government departments no longer wanted to collaborate.

Another reason for low uptake of the illegal working closure notice powers might be that the Home Office’s guidance to frontline immigration officers is more restrictive than the power provided for in the Immigration Act 2016. The guidance directs them to “use a closure notice in the most serious cases, where previous civil penalties and/or convictions have failed to change employer behaviour and, usually, where a significant proportion of workers on the premises at the time of the visit are illegal”.

Consider as well that there is no revenue to be gained through issuing illegal working closure notices. In contrast, illegal working penalties generate millions of pounds a year.

The Chief Inspector’s report also notes that immigration enforcement activities in general focus disproportionately on restaurants. The concentration on restaurants apparently stems from immigration officers’ reliance on allegations received from members of the public for intelligence. No data is available regarding the sectors in which businesses that have received closure notices operate. However, media reports of illegal working closure notices relate exclusively to restaurants, e.g. Yasmin’s in Newcastle Emlyn, Wales and Tayyabs in London.

More broadly, the report describes a lack of coherence in immigration enforcement strategy after Windrush. A manifestation of the reluctance of other government bodies to engage with immigration enforcement was the cessation of Illegal Working Steering Group meetings in 2017. The Steering Group was supposed to ensure that the Home Office’s strategic direction for prevention of illegal working was realised. If the Chief Inspector’s verdict is to be believed, there is no strategic direction.

The Chief Inspector’s recommendations and their potential effects

Illegal working closure notices could yet be revived as the Home Office shifts focus from civil penalties and removals to enforcement measures with greater deterrent effects. The Chief Inspector recommended “exploring whether more effective use could be made of . . . Closure Notices.” The Home Office confirmed in its official response that it will do so, proposing “a feasibility study on whether to introduce a systematic referral process for persistent non-compliance.”

The Chief Inspector also recommended developing intelligence capabilities and deploying officers to businesses in sectors other than the restaurant sector. The Home Office accepted the recommendation. If implemented, this could mean an expansion of immigration enforcement activity to many more UK businesses.

In addition to exploring the use of closure notices, the Chief Inspector recommended looking into the use of sponsor licence revocations. Revocation of a sponsor licence can effectively shut down an organisation. Consequences include losing all sponsored workers, reputational damage and restrictions on sponsoring workers in future. Nevertheless, the government recently announced that it would use sponsor licence revocation to punish organisations for behaviour unrelated to the immigration system. Deploying the same threat in the illegal working context would not, therefore, be a drastic step.

The previous government’s proposals for a future immigration system would expand the sponsorship system to many more UK organisations by making medium-skilled roles eligible and by streamlining processes. Whether and the extent to which those proposals will be abandoned by the current government or future ones remains unknown. If sponsorship is expanded, the effect of the Home Office relying more on sponsor licence revocations could be significant.

In its response to the Chief Inspector’s report, the Home Office committed to publishing the key points of an updated strategy and action plan to tackle illegal working. The recent revision of the government’s no-deal immigration arrangements for EU citizens arriving after Brexit, which placed a greater emphasis on the enforcement of those arrangements, might mean that the Home Office has already started to turn its attention to an updated prevention of illegal working strategy.