- BY CJ McKinney

Old convictions very much count towards a new deportation order

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Someone sentenced to more than four years’ imprisonment is in the most serious category of offender for the purposes of deportation law, no matter how long ago that sentence was, the Court of Appeal has confirmed. The case is OH (Algeria) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2019] EWCA Civ 1763.

Second attempt at deportation

OH had a tangled immigration history and a “long history of criminal offending”. In 2004, he was sentenced to eight years for grievous bodily harm and the Home Office tried to deport him. He successfully appealed and was thereafter granted discretionary leave to remain.

In 2015, OH was convicted of assaulting his eldest daughter. This time the sentence was 12 months’ imprisonment. The Home Office sought to deport him again, triggering this litigation.

The First-tier Tribunal allowed OH’s appeal. It noted that four of OH’s five children had disabilities of one form or another. The effect of OH’s deportation on his wife and children would, the tribunal found, be “unduly harsh”: section 117C of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Because OH had been convicted of a sentence of more than four years’ imprisonment, that was not enough: he could still be deported unless there were “very compelling circumstances” in his case. The tribunal went on to find that there were: OH was facing at least a ten-year ban on visiting the UK, limiting his ability to be with his young family. It also noted that he had been living in the UK continuously for 23 years.

The Upper Tribunal found these reasons were “far from compelling”. Yes, his children would be deprived of “the physical presence and love and affection of their father”, but these were simply “natural consequences” of separation. There was also insufficient attention given to the specific impact on individual children.

Relevance of the old eight-year sentence

OH had to invoke “very compelling circumstances” because he had been sentenced to more than four years’ imprisonment, back in 2004. But the law only changed to that effect many years after that conviction. The main legal issue for the Court of Appeal was whether that old conviction still triggered the “very compelling circumstances” test, over and above the “unduly harsh” test.

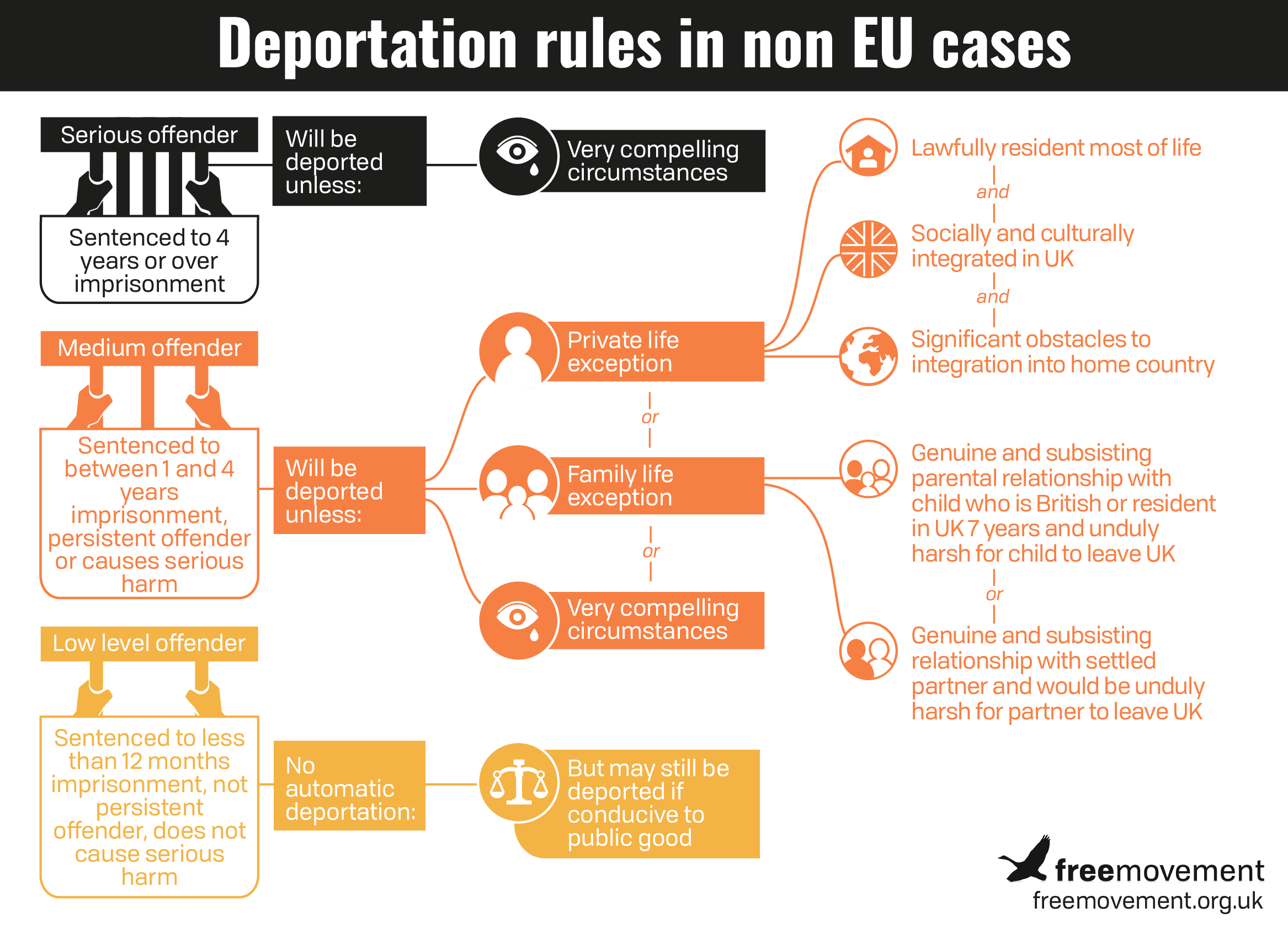

OH argued that what mattered was “the offence that triggered the deportation and not the offender’s entire criminal history”. On this interpretation, OH was only in the medium category of offender (see graphic above).

Lord Justice Irwin rejected that argument, holding that references in deportation law to a “crime”, “offence” or “period of imprisonment” in the singular didn’t rule out consideration of multiple crimes/offences/periods of imprisonment. There was also ample authority for the idea that past offending counts towards a fresh deportation order: Johnson (Deportation – 4 years imprisonment) [2016] UKUT 282 (IAC); Rexha (section 117C – Earlier Offences) [2016] UKUT 335 (IAC); and mostly recently MA (Pakistan) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2019] EWCA Civ 1252 (discussed on Free Movement here).

Justifying “very compelling circumstances”

Having decided that very compelling circumstances were required, the Court of Appeal then considered whether the First-tier Tribunal was right to find that those existed. Irwin LJ agreed that the tribunal’s reasoning was not detailed enough:

it seems to me that the FtT did indeed fail at the stage of considering whether “very compelling circumstances” arose. As a matter of language and logic, this is a very high bar indeed. The tribunal or court concerned cannot properly get to that stage unless and until it has found that the consequences of deportation will be not merely harsh, but “unduly” harsh. This must in effect mean “so harsh as to outweigh the public interest in deportation”, that public interest being the general one.

He went on:

It will be obvious that to go beyond that means a close analysis of the offender’s criminality, a recognition of the degree to which that elevates the public interest in the specific deportation, and then a clear consideration of whether (in this instance) the impact on family life would represent “very compelling reasons” so as to tip the balance… The FtT did not proceed clearly enough in that way.

First-tier judges “are not obliged to write extensive essays or indulge in an anxious parade of learning”. But, Irwin LJ held, they do have to be “more than usually clear” in their reasoning in order to back up a finding of very compelling circumstances.

Basically, tribunal judges seeking justify a controversial deportation decision should read Nick’s post: Blocking deportation: seven tips for an appeal-proof tribunal judgment.