- BY Nick Nason

Child abuse victim given deportation reprieve

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

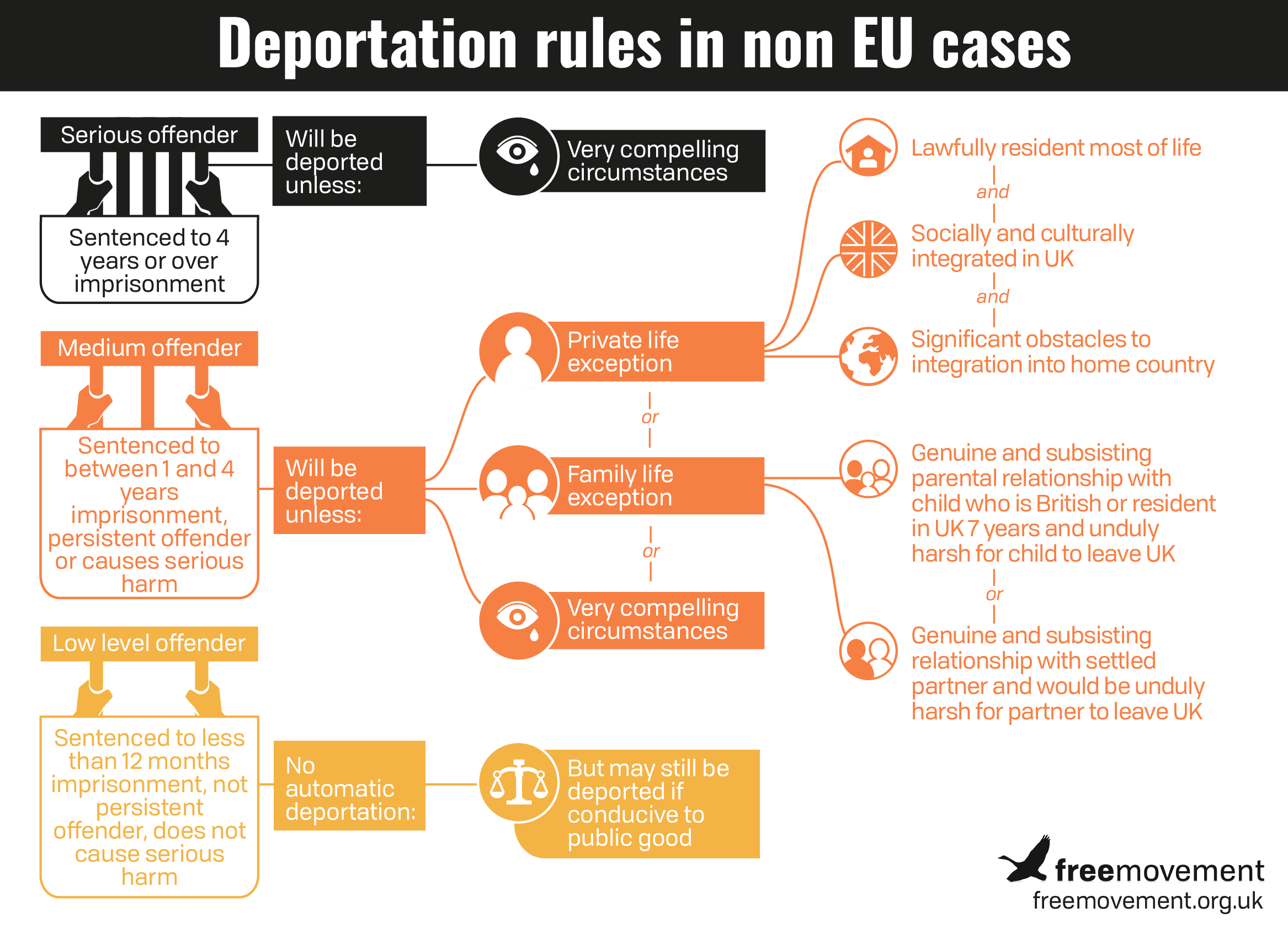

The Court of Appeal has given judgment in CI (Nigeria) v SSHD [2019] EWCA Civ 2027, providing further guidance on the law relating to the deportation of foreign criminals, and in particular on the meaning in section 117C(4) of the Nationality Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 of “lawful residence”, “social and cultural integration”, and “very significant obstacles” to integration.

Deporting long-term resident offenders: a brief recap

The public interest requires the deportation of foreign national offenders who have been sentenced to a period of imprisonment of between one and four years unless they fit within a statutory exception under section 117C(4) or 117C(5).

The 117C(4) exception is designed to reflect a person’s right to a private life as provided for by Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In order to fall within the exception an individual must show that

(a) he has been lawfully resident in the United Kingdom for most of his life

(b) he is socially and culturally integrated in the United Kingdom, and

(c) there would be very significant obstacles to his integration into the country to which he is proposed to be deported

The fact that this appeal has now been before the courts for almost six years, including now for a second time before the Court of Appeal, and *spoiler alert* is being remitted to the Upper Tribunal for further re-hearing, shows the extent of judicial disagreement as to the meaning of these terms.

Arrived in the country aged one

CI arrived in the UK in 1994 as a visitor when he was a year old with his mother and sisters. The family overstayed, with various applications to regularise their stay failing, until they all eventually received indefinite leave to remain in October 2010. The judgment describes a horrendous upbringing

CI was subjected as a child to sustained physical, verbal and emotional abuse by his mother. As well as suffering physical chastisement, CI and his siblings were frequently denied food and were left locked in the house for long periods. The home conditions were very dirty and CI was often denied access to the bathroom. He and his siblings had very few possessions. CI’s mother was a drug user and she would send CI to buy drugs for her or to beg for money from neighbours.

He was eventually taken into care after his mother refused him entry to the family home. Despite these inauspicious beginnings, CI obtained six GCSEs and two AS levels, and began studying for a Foundation Degree at Birkbeck.

However, he committed a number of criminal offences including theft and robbery and was sentenced in 2013 to 28 months’ detention in a Young Offender Institution. During this period of incarceration he was sectioned for a time, and was later diagnosed as suffering from a major depressive disorder with some significant post-traumatic traits.

A long and winding appeal

In July 2014, as a convicted foreign national sentenced to longer than 12 months, a deportation decision was made.

CI was initially successful before the First-tier Tribunal, which allowed his appeal in 2015. This was overturned by the Upper Tribunal, whose decision was in turn reversed by the Court of Appeal in 2017, which sent it back to the Upper Tribunal. It was the re-making of that Upper Tribunal decision in 2018 which was the subject of the current appeal before the Court of Appeal (2019).

The judgment

In its decision that the Upper Tribunal had once again erred in law, the Court of Appeal has provided some useful commentary on the key tests that apply in cases involving long-term offenders seeking to show they come within the section 117C(4) private life exception.

Lawful residence (paragraphs 27-55)

Amongst other arguments, CI’s legal team attempted to rely on SC (Jamaica) v SSHD [2017] EWCA Civ 2112 to suggest that “lawful residence” meant the same in section 117C(4)(a) as it did in paragraph 276A of the Immigration Rules. This would mean that a status such as “temporary admission” – which CI had for a time as a dependant on an asylum claim made by his mother – would count as lawful residence.

The court refused to accept this “enterprising” argument, upholding the Upper Tribunal’s finding that, outside of circumstances where a person applies for asylum and is later successful (in which case the period between the date of claim and the grant can be considered lawful), lawful residence means where leave to enter or remain has been granted.

Social and cultural integration in the UK (paragraphs 56-82)

A particularly objectionable finding made by deportation tribunals in recent years is that people who have lived in the UK for all or the vast majority of their lives are, due to criminal conduct, not considered to be socially and culturally integrated within the meaning of section 117C(4)(b) (see Akinyemi v SSHD [2017] EWCA Civ 236).

This was the position of the Upper Tribunal here. It found that although CI was socially and culturally integrated in the UK as a child, this integration was “broken” by his criminal offending and periods in detention, and was not subsequently re-established. The Court of Appeal found that this was an erroneous approach and that:

The judge should simply have asked whether – having regard to his upbringing, education, employment history, history of criminal offending and imprisonment, relationships with family and friends, lifestyle and any other relevant factors – CI was at the time of the hearing socially and culturally integrated in the UK. The judge should not, as he appears to have done, have treated CI’s offending and imprisonment as having severed his social and cultural ties with the UK through its very nature, irrespective of its actual effects on CI’s relationships and affiliations – and then required him to demonstrate that integrative links had since been “re-formed”.

The court also took issue with Upper Tribunal judge’s repeated references to integration being “broken” by anti-social behaviour. This, it said, gave the impression

that he saw the relevant question as being whether, through the nature and seriousness of his offending, a “foreign criminal” has broken the social contract which entitles him to the protection of the state. That, however, is not the relevant test, which should be concerned solely with the person’s social and cultural affiliations and identity.

The idea, found the Court of Appeal, that CI was not socially and culturally integrated in the UK had “an air of unreality about it”.

Very significant obstacles (paragraphs 83-91)

The Upper Tribunal had found that CI would not face very significant obstacles to integrating into life in Nigeria, due to a level of knowledge of Nigerian culture he was assumed to have acquired from his mother.

[ebook 20010]This is despite the abuse suffered by CI at his mother’s hands which, the tribunal held, was not enough to “demonstrate that he lacked familiarity with his mother’s cultural way of life”.

The Court of Appeal found that this put the onus on CI to prove that he was not familiar with Nigerian culture, rather than requiring some factual basis for finding that he was. The court clarified the correct approach:

An inference that an immigrant who has no memory of his country of origin (having left it as an infant) must nevertheless have acquired some knowledge of its culture and traditions through his upbringing might in some cases be a reasonable one to draw. But on the evidence before the Upper Tribunal there was no reasonable basis for drawing such an inference in this case.

The Court of Appeal also criticised the tribunal for failing to address the mental health issues outlined in psychiatric reports before the tribunal, and for making unfounded assertions regarding “the availability of health/welfare services” in Nigeria, for which there was no evidence.

Very compelling circumstances (92-114)

There is a welcome restatement and discussion of the Maslov principles in long-term resident offender cases (103-114). The Court of Appeal found that

it would not be consistent with the test of proportionality under article 8, which involves a balancing exercise, to treat the principles stated in the Maslov case as inapplicable to a settled migrant with a right of residence just because the individual concerned, although present in the country since early childhood, has not had a right of residence for a particular length or proportion of their time in the host country.

Whilst confirming that the whole rationale behind the Part 5A regime is to achieve an outcome which is compatible with Article 8, the Court of Appeal found that

the Upper Tribunal judge erred in regarding the principles established in Maslov as inapplicable in the present case because CI was not a settled migrant for most of his childhood.

The Court of Appeal found that this undermined the conclusions on the question of whether very compelling circumstances existed.

Lord Justice Leggatt, giving the lead judgment, had two other important reasons that fatally undermined the tribunal’s conclusions on the question of very compelling circumstances.

One was the severity of the difficulties and suffering that CI would potentially face if sent to Nigeria, in combination with his mental health issues:

There is a material difference between returning an immigrant to a country with which he retains some social and cultural ties and deporting him to a country with which he has none and which, in the words of CI’s sister in this case, “is as foreign to us as China”.

The court also found that the Upper Tribunal had not properly taken contextualised CI’s offending: he was young at the time, had not reoffended, and his behaviour must be seen through the prism of his tragic upbringing, a child on the receiving end of years of abuse and neglect. The court below had paid this no heed.

This was an excellent result for CI’s legal team, who were eventually funded by the Legal Aid Agency via exceptional case funding (having initially done much work either at risk or without any funding cover). Given the expert reports that were adduced in the case (at least two), it is safe to say that without legal aid, this result would not have been achieved.

The matter is remitted to the Upper Tribunal, which will hear the case for the third time next year.

SHARE