- BY Iain Halliday

Is carrying a knife enough to get you deported?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Earlier this year the Court of Appeal looked at the meaning of an offence causing “serious harm” for the purposes of deportation law. Being convicted of such an offence is one of the ways a person can find themselves facing automatic deportation from the UK.

The Upper Tribunal has now considered, and re-stated, the general principles on whether a particular offence has caused serious harm. The case is Wilson (NIAA Part 5A; deportation decisions) [2020] UKUT 350 (IAC). It concerned Mr Wilson, a citizen of St Lucia who had been convicted of possessing a knife in a public place. He was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment.

General principles

The headnote, which replicates paragraph 53 of the judgment, provides a helpful summary of the general principles:

The current case law on “caused serious harm” for the purposes of the expression “foreign criminal” in Part 5A of the 2002 Act can be summarised as follows:

(1) Whether P’s offence is “an offence that has caused serious harm” within section 117D(2)(c)(ii) is a matter for the judge to decide, in all the circumstances, whenever Part 5A falls to be applied.

(2) Provided that the judge has considered all relevant factors bearing on that question; has not had regard to irrelevant factors; and has not reached a perverse decision, there will be no error of law in the judge’s conclusion, which, accordingly, cannot be disturbed on appeal.

(3) In determining what factors are relevant or irrelevant, the following should be borne in mind:

(a) The Secretary of State’s view of whether the offence has caused serious harm is a starting point;

(b) The sentencing remarks should be carefully considered, as they will often contain valuable information; not least what may be said about the offence having caused “serious harm”, as categorised in the Sentencing Council Guidelines;

(c) A victim statement adduced in the criminal proceedings will be relevant;

(d) Whilst the Secretary of State bears the burden of showing that the offence has caused serious harm, she does not need to adduce evidence from the victim at a hearing before the First-tier Tribunal;

(e) The appellant’s own evidence to the First-tier Tribunal on the issue of seriousness will usually need to be treated with caution;

(f) Serious harm can involve physical, emotional or economic harm and does not need to be limited to an individual;

(g) The mere potential for harm is irrelevant;

(h) The fact that a particular type of offence contributes to a serious/widespread problem is not sufficient; there must be some evidence that the actual offence has caused serious harm.

How did these principles apply to Mr Wilson’s circumstances?

The knife-related conviction

Section 139 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 creates an offence of having an article with a blade or point in a public place. The rationale for making this a crime is to prevent serious harm — those who carry knives around tend to end up using them.

This, in a nutshell, was the Home Office’s argument. It was assisted by the remarks of the judge who sentenced Mr Wilson:

The dangers of knife crime are all too obvious to all of us. You, in particular, because of your unfortunate family circumstances, can hardly say that you are unaware of the consequences of, often young, men carrying knives and using them or having them used on them in public places.

Every day, it seems, on television, we see sad tales of families torn apart, of lives wrecked, by the use of unlawful knives on our streets. That is why carrying a knife in a public place is so serious. [Paragraph 6]

The “unfortunate family circumstances” referred to Mr Wilson’s uncle being stabbed, and his cousins threatened. He was carrying the knife for fear that he too might be attacked.

The First-tier Tribunal had relied on the fact that there was no suggestion Mr Wilson was going to use the knife. He had not brandished it or shown it to anybody. He owned up to possession of the knife when spoken to by police. As such, his crime was not one that had caused “physical or psychological harm”.

The Home Office appealed on the basis that the First-tier Tribunal judge should not have gone behind the sentencing remarks, and had failed to consider the potential for serious harm had the police not intervened when they did. An understandable point, but one difficult to reconcile with the need outlined above to show that the offence actually caused serious harm. It is not enough that a particular type of offence contributes to a serious/widespread problem.

Serious crimes don’t always cause serious harm

The Upper Tribunal accordingly found in Mr Wilson’s favour on the issue of serious harm:

Judge Kainth [in the First-tier Tribunal] was well aware of the reason that Parliament has seen fit to criminalise the possession of a bladed article in a public place. In doing so, Parliament intended to reduce the prevalence of crimes of violence involving knives, by criminalising their possession, in certain circumstances.

As we have seen, however, in order for the offence to be categorised as one that has “caused serious harm”, there must be some evidence that actual harm has been caused. In the case of the claimant, Judge Kainth was entitled to find that no such harm had ensued. The claimant had not brandished the knife. Whilst the claimant’s explanation was, of course, not a valid mitigation of the offence of possession – since carrying a knife for the avowed purpose of self-defence is part of the problem that the criminalisation of knife possession is intended to address – it was not an irrelevant factor in the judge’s assessment of whether the offence had “caused serious harm” for the purposes of Part 5A of the 2002 Act. [56]-[57]

So the First-tier Tribunal judge was entitled to find that the offence was not one which had caused serious harm. Unfortunately he then went a bit off track, as that wasn’t the end of the matter.

Discretionary deportation and human rights

Judge Kainth had concluded that the deportation order was not in accordance with the law. As a result, he felt it wasn’t necessary to consider Mr Wilson’s Article 8 right to private and family life — his appeal was to be allowed anyway.

But as noted by the Upper Tribunal:

In this jurisdiction, it is often dangerous for a judicial fact-finder to decide that he or she can deploy a “short cut”, so as to avoid the exercise inherent in Article 8(2) of deciding whether removal of an individual would be a disproportionate interference with the Article 8 rights of the latter and/or some other person or persons. Such is the case here. [63]

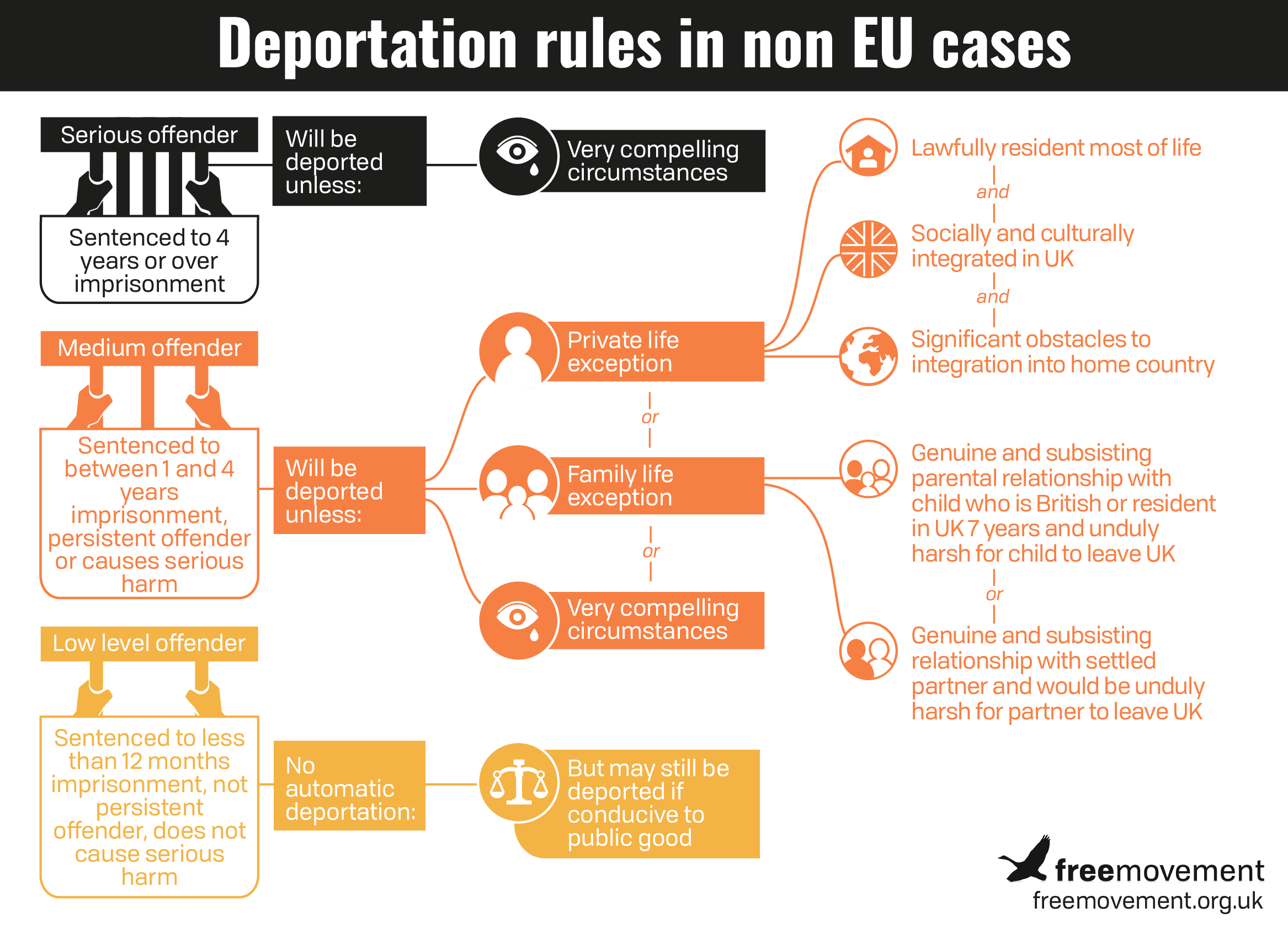

Why was the human rights issue still important? The Home Secretary can deport anyone who is not a British citizen providing she deems deportation to be “conducive to the public good”. As our graphic at the top of the page shows, the person does not have to meet the definition of “foreign criminal” in the automatic deportation legislation to be deported. As such, the legality of the underlying deportation decision was unaffected by the finding that Mr Wilson had not been convicted of an offence which had caused serious harm.

The Upper Tribunal also noted that there is technically no right of appeal against a deportation order. There was only an appeal against the Home Office’s refusal of Mr Wilson’s human rights claim to remain in the UK in spite of the deportation order.

So, having reached his decision on whether Mr Wilson had been convicted of an offence which caused serious harm, the judge should have gone on to consider whether his removal from the UK was proportionate. In doing so the effect of deportation on Mr Wilson and his family, and section 117B of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, needed to be considered. The judge had not carried out this exercise. The case was sent back to him to do so.

There is a second section of the headnote dealing with this issue:

(1) In a human rights appeal, the decision under appeal is the refusal by the Secretary of State of a human rights claim; that is to say, the refusal of a claim, defined by section 113(1) of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, that removal from the United Kingdom or a requirement to leave it would be unlawful under section 6 of the 1998 Act. The First-tier Tribunal is, therefore, not deciding an appeal against the decision to make a deportation order and/or the decision that removal of the individual is, in the Secretary of State’s view, conducive to the public good. It is concerned only with whether removal etc in consequence of the refusal of the human rights claim is contrary to section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998. If Article 8(1) is engaged, the answer to that question requires a finding on whether removal etc would be a disproportionate interference with Article 8 rights.

(2) The Secretary of State’s decisions under the Immigration Act 1971 that P’s deportation would be conducive to the public good and that a deportation order should be made in respect of P would have to be

unlawful on public law grounds before that anterior aspect of the decision-making process could inform the conclusion to be reached by the First-tier Tribunal in a human rights appeal.

SHARE