- BY CJ McKinney

Immigration white paper published

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The government has published its plan spelling the end of free movement. A long-awaited white paper on post-Brexit migration proposes that EU workers would in future have to earn a minimum salary in a job requiring A-level qualifications or above to be sponsored for a UK work visa. “Low-skilled” workers not meeting these criteria would be restricted to short-term visas of one year at a time.

An economic annex admits that the effect of these changes would be to damage the British economy:

We estimate these long-term work proposals could reduce the UK workforce by between 200,000 and 400,000 EEA nationals over the first five years, which we estimate could mean GDP is between 0.4 per cent and 0.9 per cent lower than it otherwise would have been in 2025. This represents a reduction in GDP per capita of between 0.1 per cent and 0.2 per cent in 2025.

There will be a “cumulative fiscal cost [to the Treasury] of between £2 billion and £4 billion over the first five years (2021-2025)”.

The white paper would, despite the protests of businesses, essentially bring EU workers within the existing Points Based System that applies to non-EU workers — but with some tweaks. The tweaks are to accept almost all the recommendations made by the influential Migration Advisory Committee earlier this year. These include:

- Scrapping the overall cap on sponsored work visas, currently branded as Tier 2 (General)

- Lowering the skills threshold from level 6 (degree) to level 3 (A-level)

- Abolishing the Resident Labour Market Test

- Reducing the bureaucratic burden on sponsoring employers

The net result will be

a new single immigration route for skilled workers, from RQF 3 to RQF 7 (post-graduate).

Workers in this route, from RQF 3 upwards, will need to be sponsored by their employer; employers will pay an immigration skills charge and individual migrants must pay a health charge, subject to any discussions with the EU about reciprocal health care.

The MAC had proposed that the minimum salary of £30,000 be retained in this revamped system — so whatever the skill level of the role, from A-level to post-graduate, the salary would have to be £30,000 or more. This is the sole recommendation not immediately accepted. The white paper instead kicks the salary thresholds into the long grass, saying that

before confirming the level of a future salary threshold we will want to engage extensively with businesses and employers, consider wider evidence of the impact on the economy, and take into account current pay levels in the UK economy.

By contrast, “low-skilled” workers who do not meet the skills and salary criteria will in future be limited to a 12-month working visa. This will be “followed by a cooling off period of a further twelve months to prevent long-term working”. There will be “restrictions on nationalities, duration and possibly numbers”. The visa will not come with the right to claim benefits, bring family member, switch onto another visa or settle in the UK.

The white paper says that this low-skilled route will be a short term measure, “for a transitional period after the UK’s exit from the EU”. 2025 is mentioned, in a rather garbled passage at paragraph 6.50, as a possible cut-off date. It will only be open to “nationals of specified countries, for example those low risk countries with whom the UK negotiates an agreement concerning the supply of labour”. If this involves discrimination between different EU member states, this is likely to be challenged by the European Union in subsequent trade negotiations. The bloc typically demands that immigration routes are open to all its citizens.

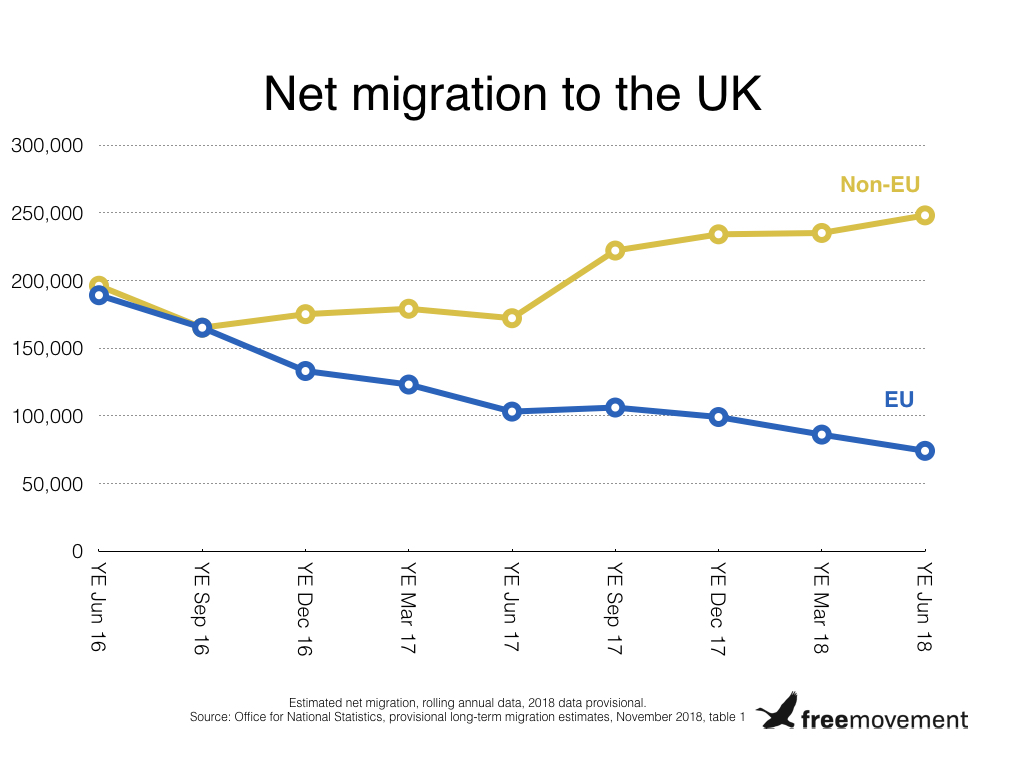

With the overall numerical cap on sponsored workers abolished, the skills and salary requirements will do the heavy lifting in keeping down the number of work visas issued. Consistent with this approach, there is no numerical target for overall net migration (the number of immigrants coming to live in the UK minus the number of emigrants). The lack of any specific reference to bringing annual net migration below 100,000 is largely symbolic, as this goal has not been close to being met since it was first set in 2011. Net migration is currently running at 250,000 a year from outside the EU alone.

The white paper also acknowledges the shortcomings of the sponsor licensing system. Instead it promises “a reformed lighter-touch, risk-based approach, such as seeking to share and utilise data already held across government, reducing the administrative burden on employers”. This may include “the use of umbrella organisations to act as sponsors” and potentially a “‘tiered’ system of sponsorship” with smaller organisations having fewer hoops to jump through.

Student and visit visa rules are also canvassed in the document, including a new six-month post study route and a consultation on “fly in, fly out” business trip arrangements for visitors.

Family migration rules are mentioned, but it appears only to reiterate what they currently are and that they will apply to new arrivals from the EU in future.

Very disappointingly, no changes at all proposed to the existing very restrictive family immigration policies and the minimum income threshold. Apart from reviewing the Life In The UK test. Massive missed opportunity to inject some humanity and flexibility into these awful rules.

— Colin Yeo (@ColinYeo1) December 19, 2018

On deportation and criminality thresholds, there are similarly no plans to reform the current system. It simply be applied to EU citizens in future. That will cause huge increase in number of deportations, although there is no obvious mention of increased enforcement capacity.

There is a short chapter on asylum that discusses some possible policy adjustments but no radical changes. An “ambitious and well-funded English language strategy” will try to help newly arrived refugees, in particular, integrate by having English lessons. The government would like to negotiate a new “Dublin” agreement for sending third country national asylum seekers back to EU countries, and there is a hint that granting asylum seekers the right to work will be looked at (paragraph 10.14). We aren’t holding our breath on either of those coming to fruition.

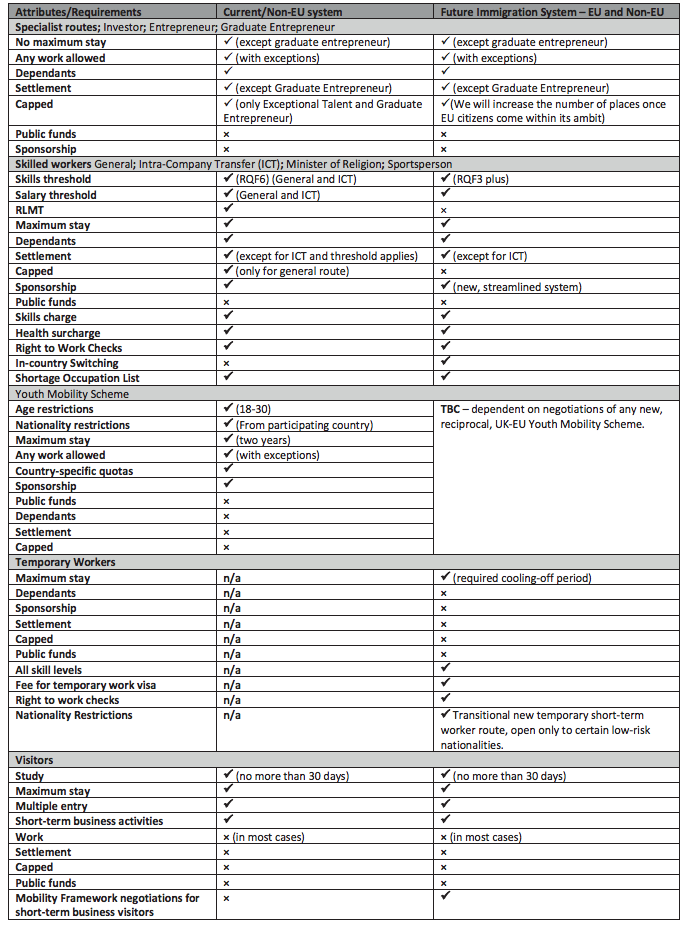

A chart summarising the main proposed changes is included:

There is also a Home Office press summary, a copy of the Home Secretary’s statement to Parliament, and an executive summary.

The new system will be phased in from 2021. It is about future migration and so will not affect EU citizens already living in the UK, who will be able to apply for “settled status” in order to stay legally after Brexit (whether or not there is a deal on an orderly exit).

It has been widely reported that ministers have been feuding over the contents of the white paper right down to the wire. The Financial Times (£), for example, says that “Philip Hammond, the chancellor, and Greg Clark, business secretary, fought a rearguard action on Tuesday to dilute the long-delayed immigration white paper, which they fear could cause serious damage to the British economy”. And, as Colin points out, Theresa May herself may not be in office much longer. With the salary threshold already on the long finger and a “12-month programme of engagement” planned to finalise other details, there is a lot still to play for in a febrile political environment.

That is even before we get to negotiations with the European Union on our future relationship with the bloc, which will ask for more liberal rules on migration for its citizens in exchange for better terms on trade. As Jo Hunt has pointed out on this blog, “the window has been left open for ‘mobility concessions’ to be made as part of the final Brexit deal, meaning that the ideas discussed above may be softened depending on the future trade deal struck with the EU”. Former mandarin Sir Ivan Rogers puts it more brutally: today’s plan “will simply disintegrate in the face of negotiating imperatives”. For all the fanfare, British immigration policy in the 2020s may not ultimately bear much resemblance to this white paper.