- BY Colin Yeo

Immigration up but not as much as expected

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe latest quarterly immigration statistics were published today. Most of the media focus is on net migration and the Office of National Statistics ONS report. Net migration turned out to be around 600,000 rather than the 700,000 or more that some had predicted.

Here, though, we’re going to focus on just one part of the picture: the Home Office statistics on grants of visas and citizenship. These figures form only one part of the net migration equation (immigration minus emigration equals net migration). Even then, the visa figures are not synonymous with the immigration part of that equation. This is because some visas are issued to migrants coming for less than a year, and these visas are not counted towards net migration at all. This would apply to students on Masters courses, for example, which typically last for nine months.

The statistics relate to the 12 month period March 2022 to March 2023.

Asylum

Asylum claims were up, the backlog is up, detention is down and asylum removals are fairly static.

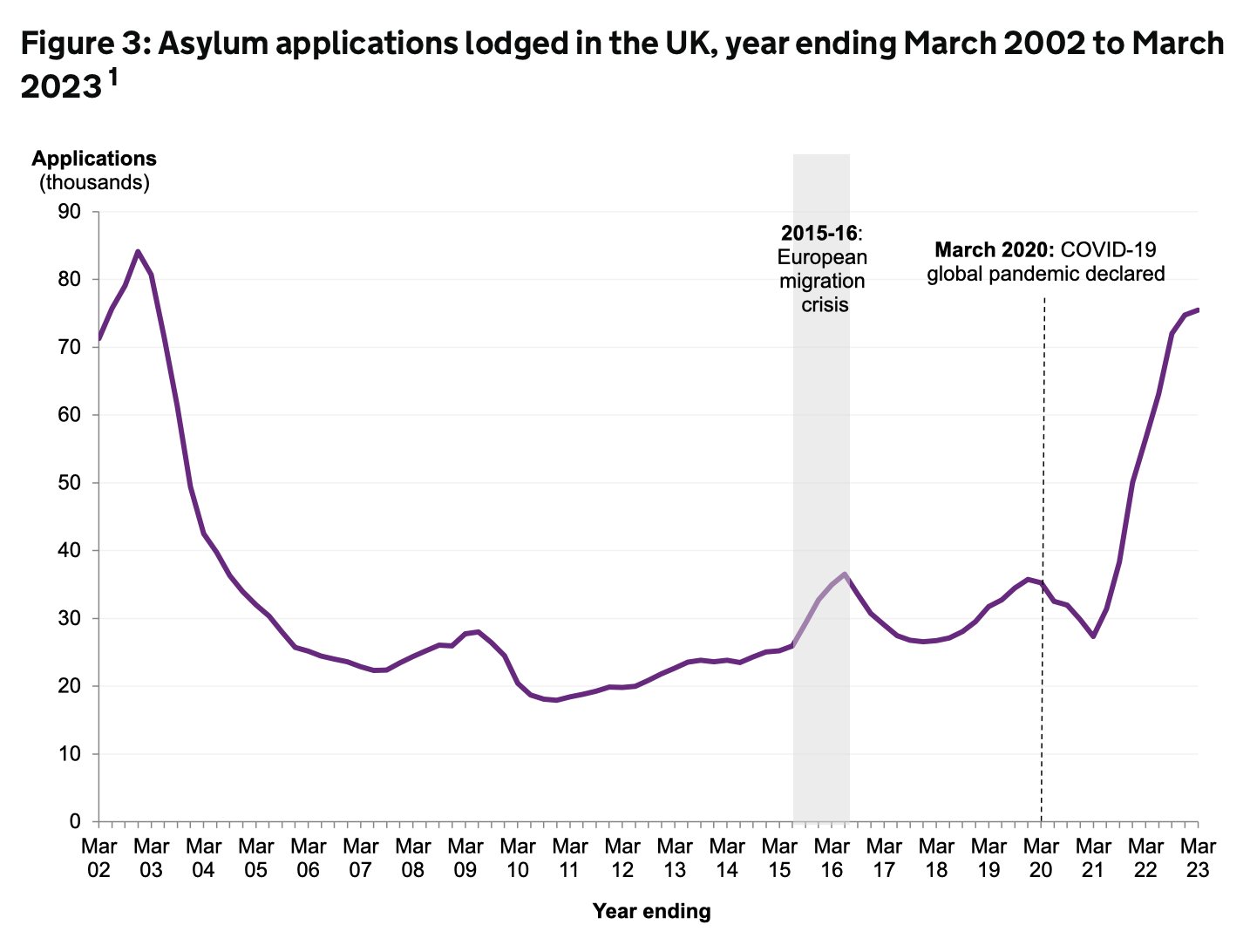

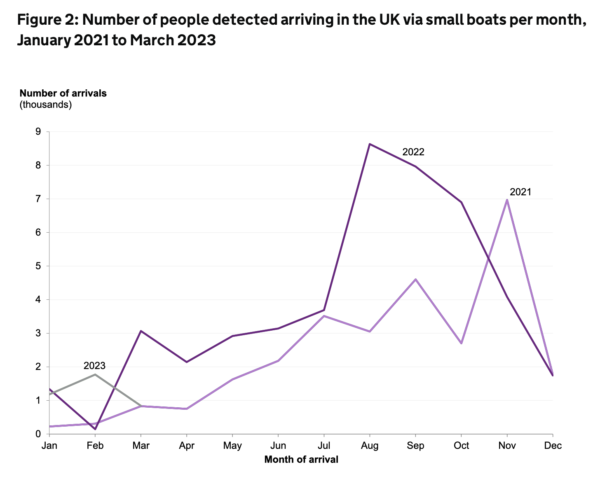

There were 75,492 asylum applications by 91,047 people. That is still below the peak in the early 2000s. The rate of increase for asylum claims seems to have tapered off a little, perhaps because of a relative fall in small boat arrivals compared to the same time last year. 3,793 people arrived in small boats in January to March 2023 compared to 4,548 in January to March 2022.

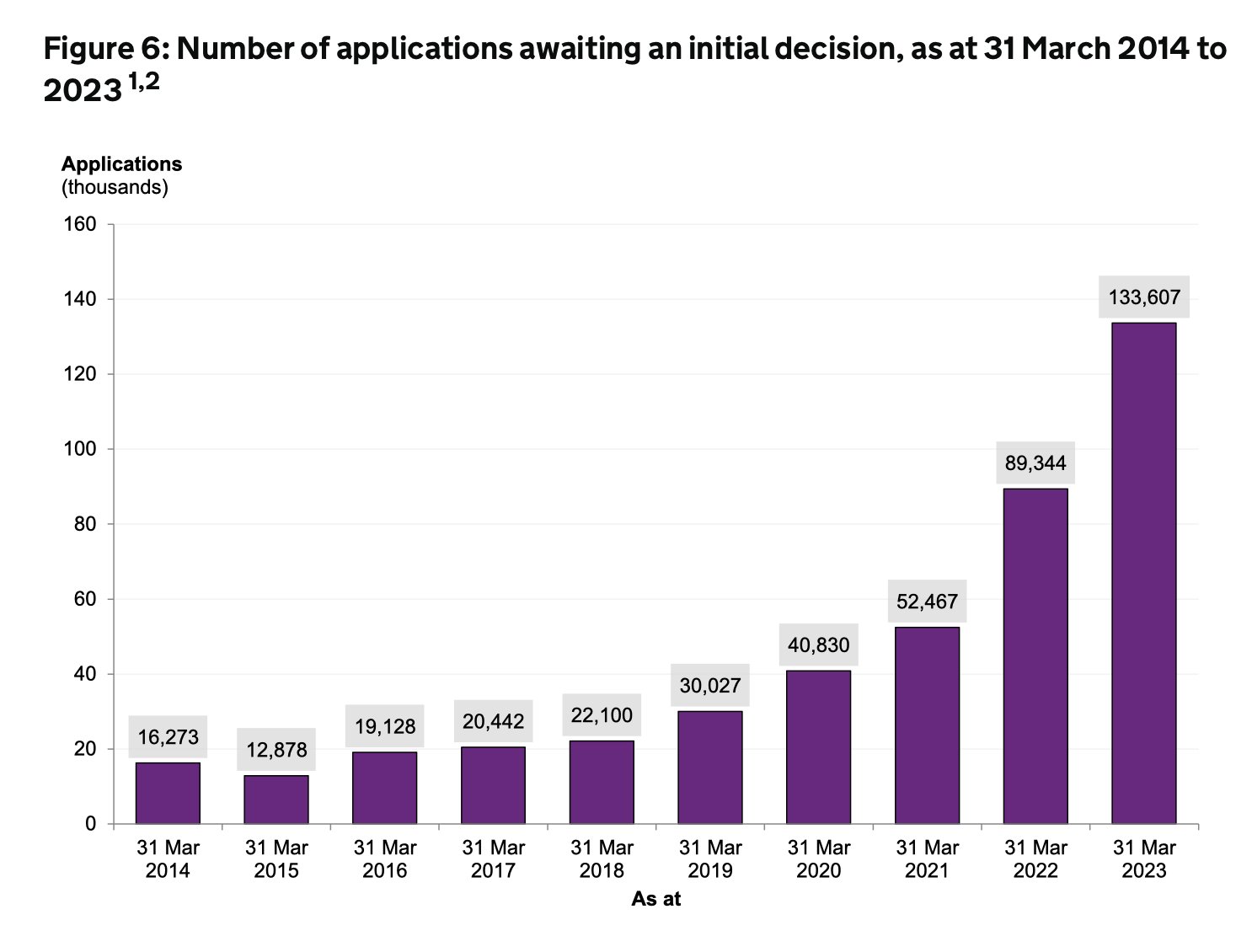

The number of asylum decisions remained woefully inadequate: just 19,706 decisions. That’s up on the previous year but nowhere near enough to keep up with arrivals, never mind start reducing the asylum backlog. There are now 1,281 asylum caseworkers, which is double the number a year or so ago. Rishi Sunak’s pledge to eliminate the backlog by the end of 2023 is looking unlikely to be met without some pretty radical action.

The result is that the asylum backlog is the biggest it has ever been. The chart below shows main applicants. The total number of actual people awaiting decisions, once dependants are included, is 172,758.

The rate of increase in the backlog has slowed and the Home Office breaks the total in two. 78,954 (59%) applications were ‘legacy’ cases made before 28 June 2022, and 54,653 (41%) had been made on or after 28 June 2022 (referred to as ‘flow cases’). The small print of Sunak’s pledge is that it is the legacy cases that will be eliminated. But he’s a long way from even that.

Anyone who has arrived after 7 March 2023 will, if or when the Illegal Migration Bill becomes law, never have their asylum claim decided.

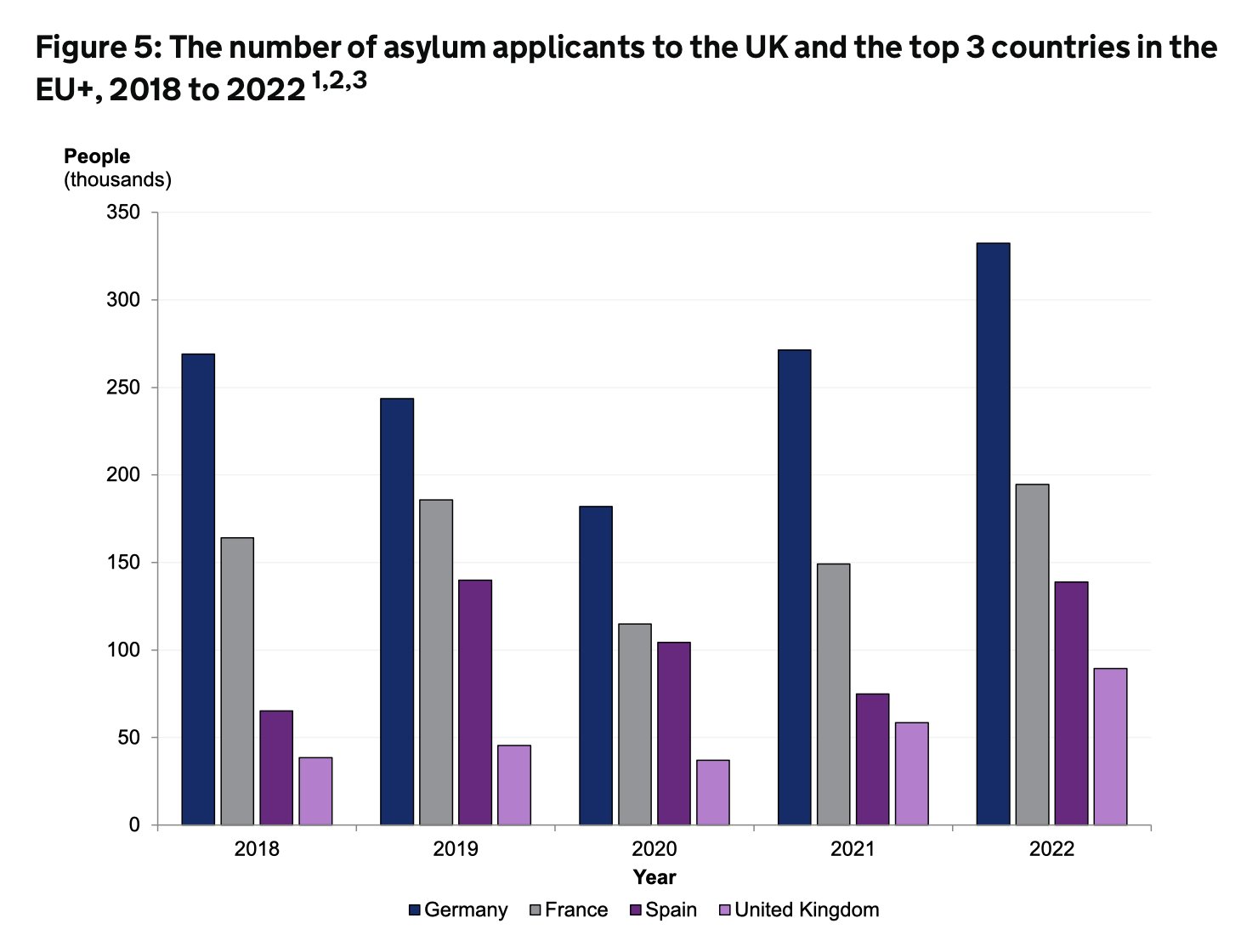

It is worth remembering that asylum claims are going up around the world and Europe. The UK still receives far, far fewer claims than other European countries, as this chart shows.

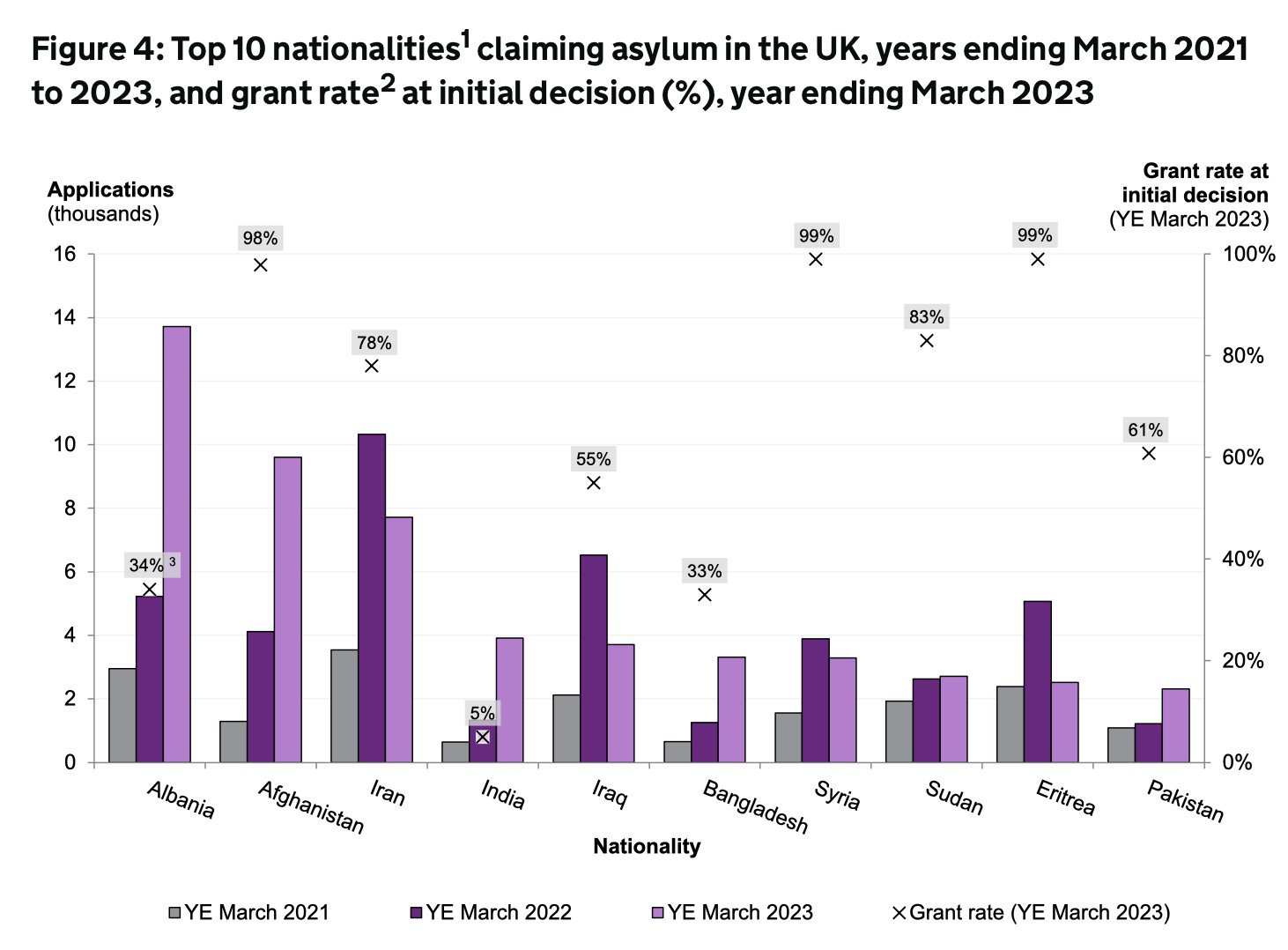

The asylum grant rate remains high, at 74%. That is before appeals, and 53% of asylum appeals were allowed. The grant rate varies considerably by country: Afghans 98%, Eritreans 99%, Syrians 99% and Sudanese 83%. Iranian success rate fell, oddly. Indian asylum claims trebled to 3,911, and they have a 5% success rate.

Detention and departure

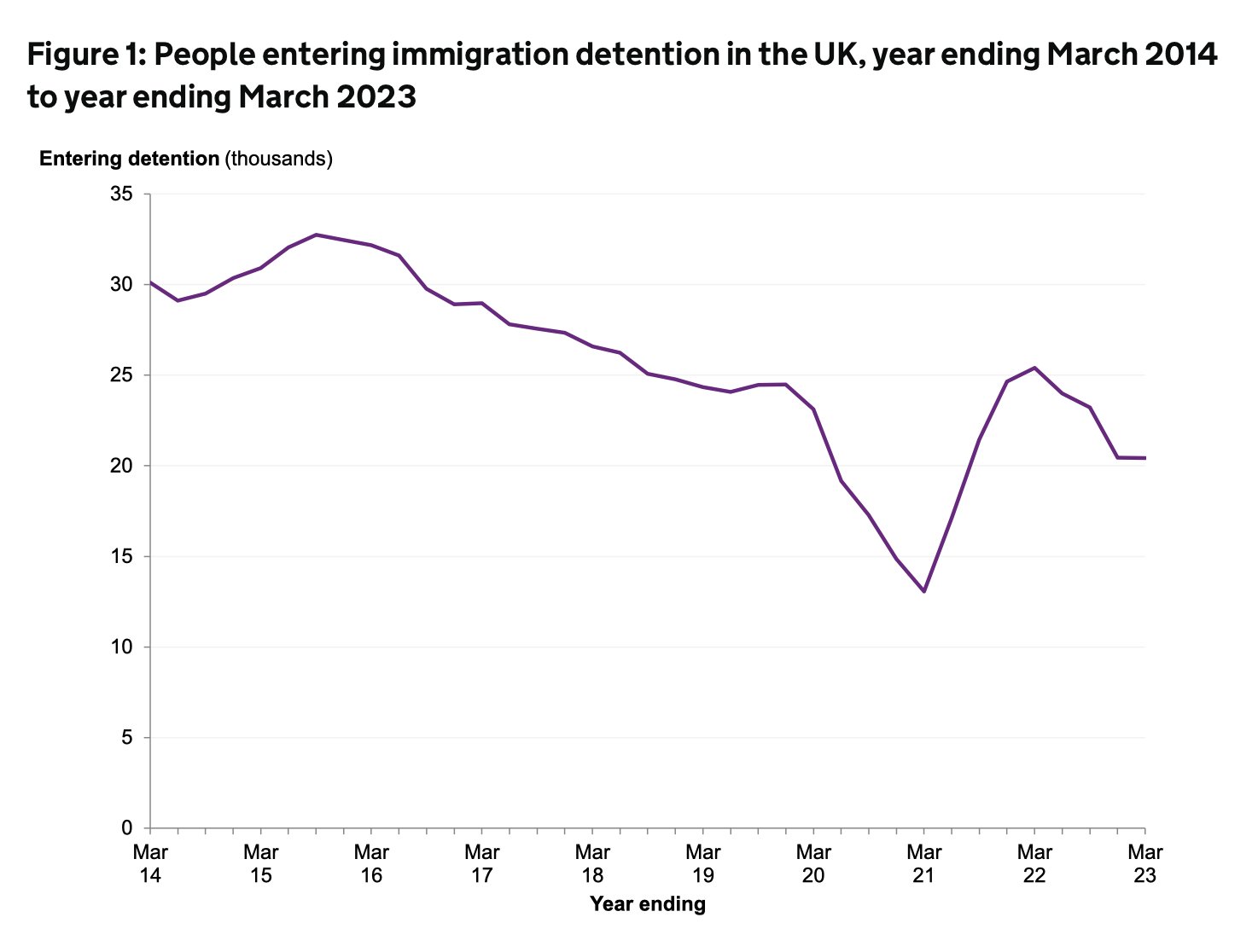

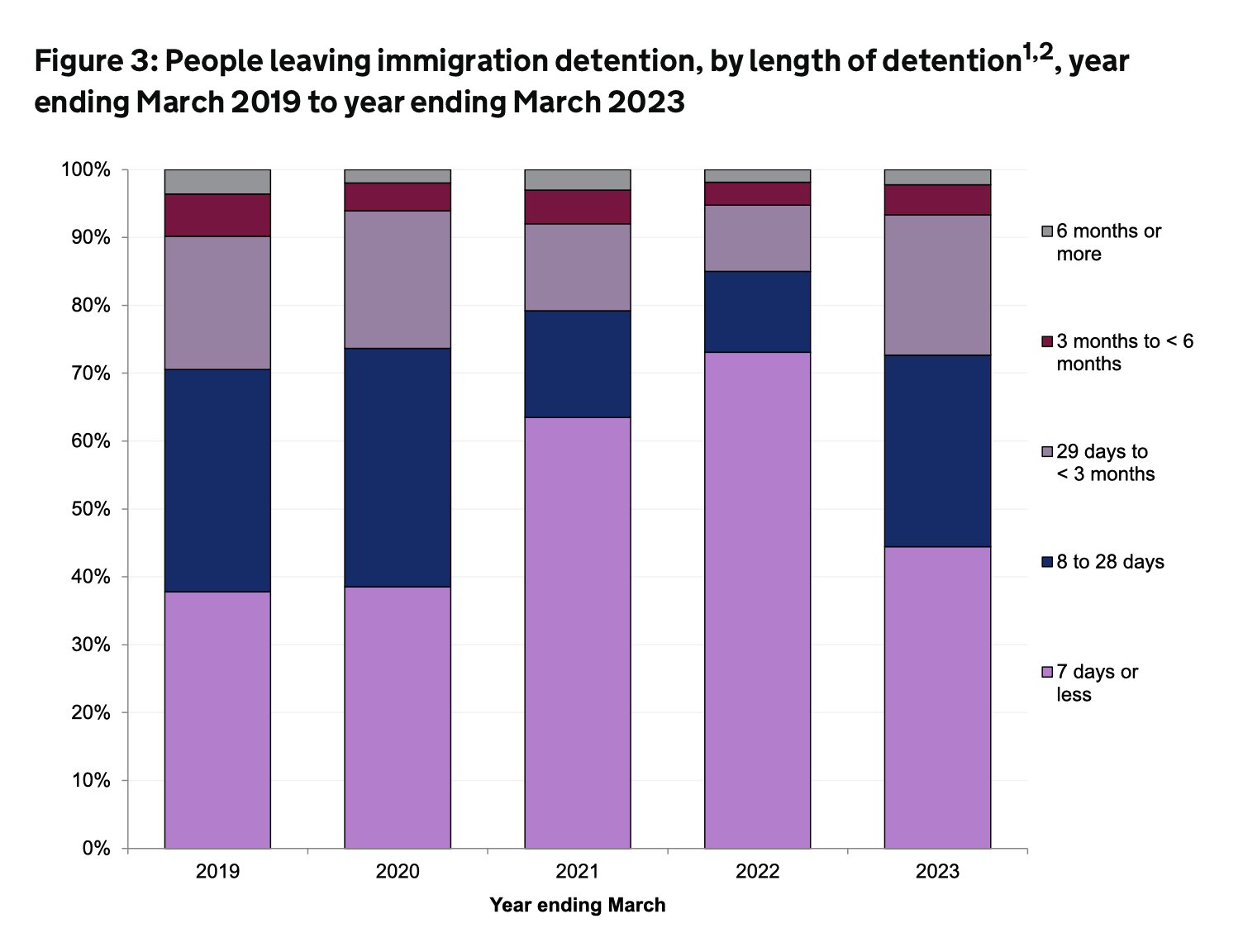

Immigration detention is down, with 20,416 people entered immigration detention in the year ending March 2023, 20% fewer than in the year ending March 2022. But the percentage of people facing longer periods of detention increased.

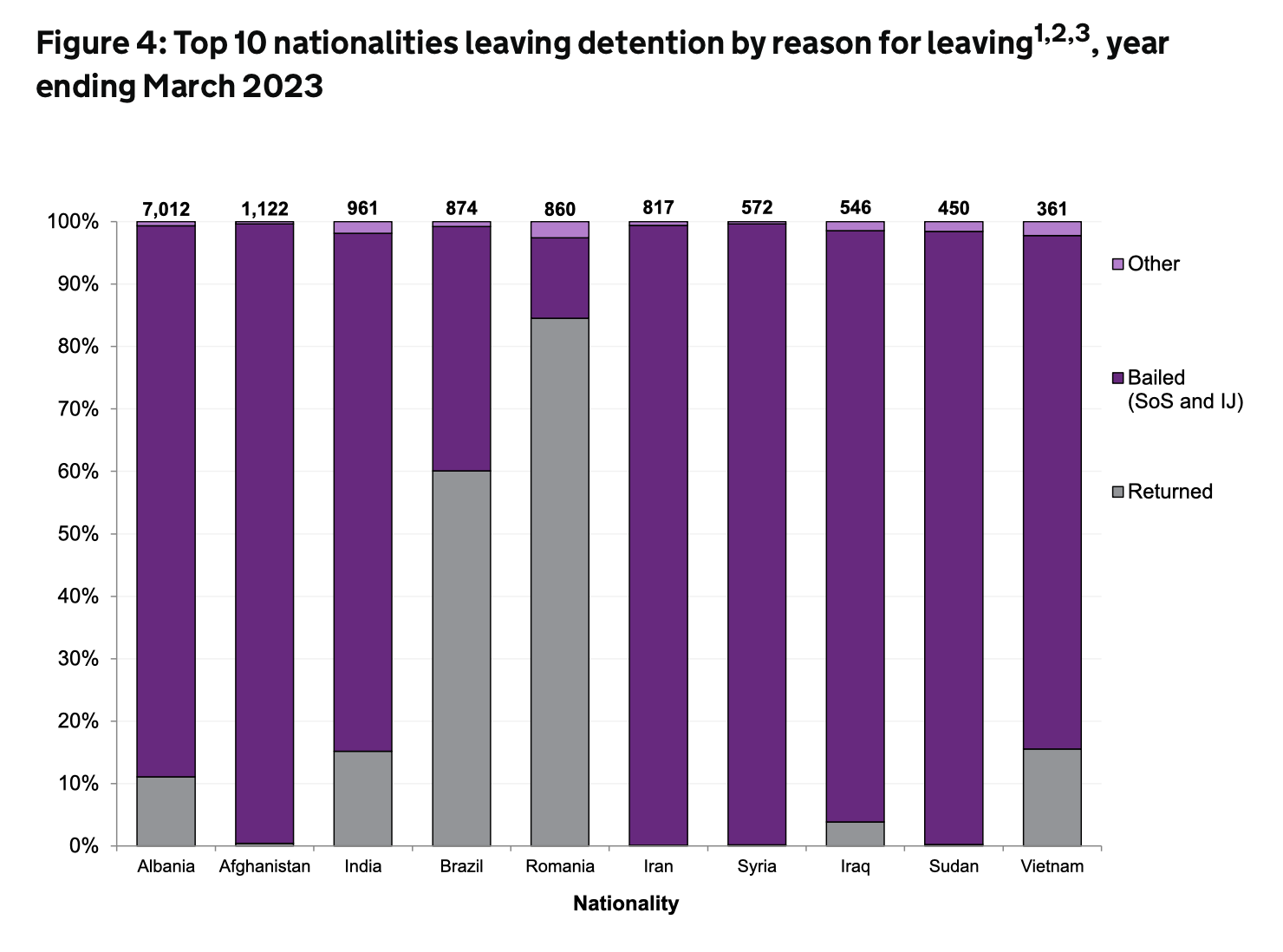

The nationalities of detainees is interesting. It shows the dual purpose of immigration detention: establishing identity in asylum claims and enforcing removal in other cases involving overstaying or criminality.

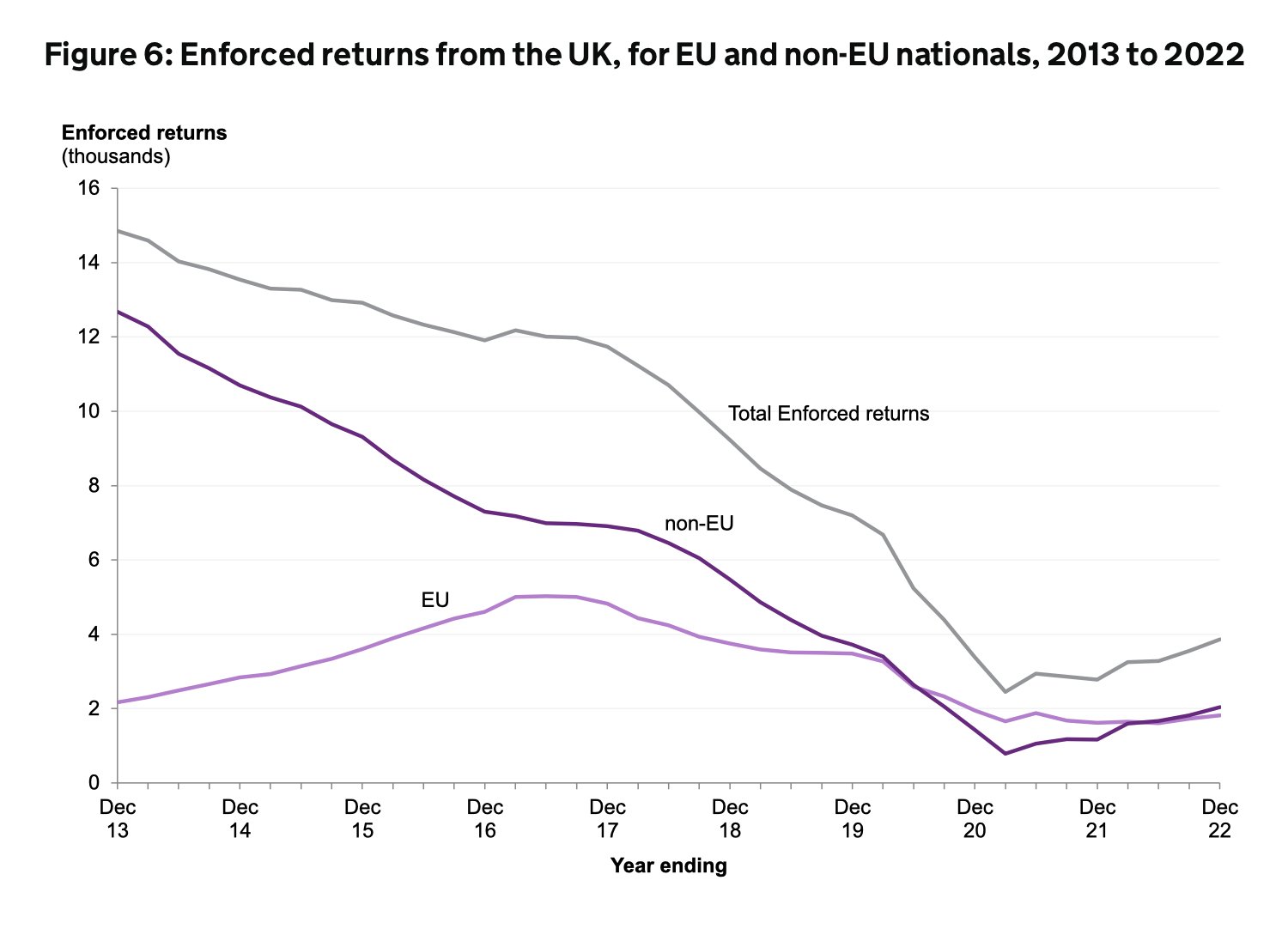

Meanwhile, enforced returns were down 46% compared to 2019 to 3,860. The vast majority of these are foreign national offenders not failed asylum seekers. Nationalities being returned mainly EU: Albania (25%), Romania (18%), Poland (8%), and Lithuania (7%). Brazil (10%).

Very few of the enforced returns are asylum-related. The method for calculating “asylum related returns” has changed, though, and the Home Office now claims 2,866 asylum related returns in last year. This is in part due to a 176% increase in Albanian voluntary returns. The stats separating out asylum enforced returns are only published annually not quarterly, and we already knew that in the whole of 2022 there were 580 enforced asylum returns (summary data set, table Ret_05).

Work

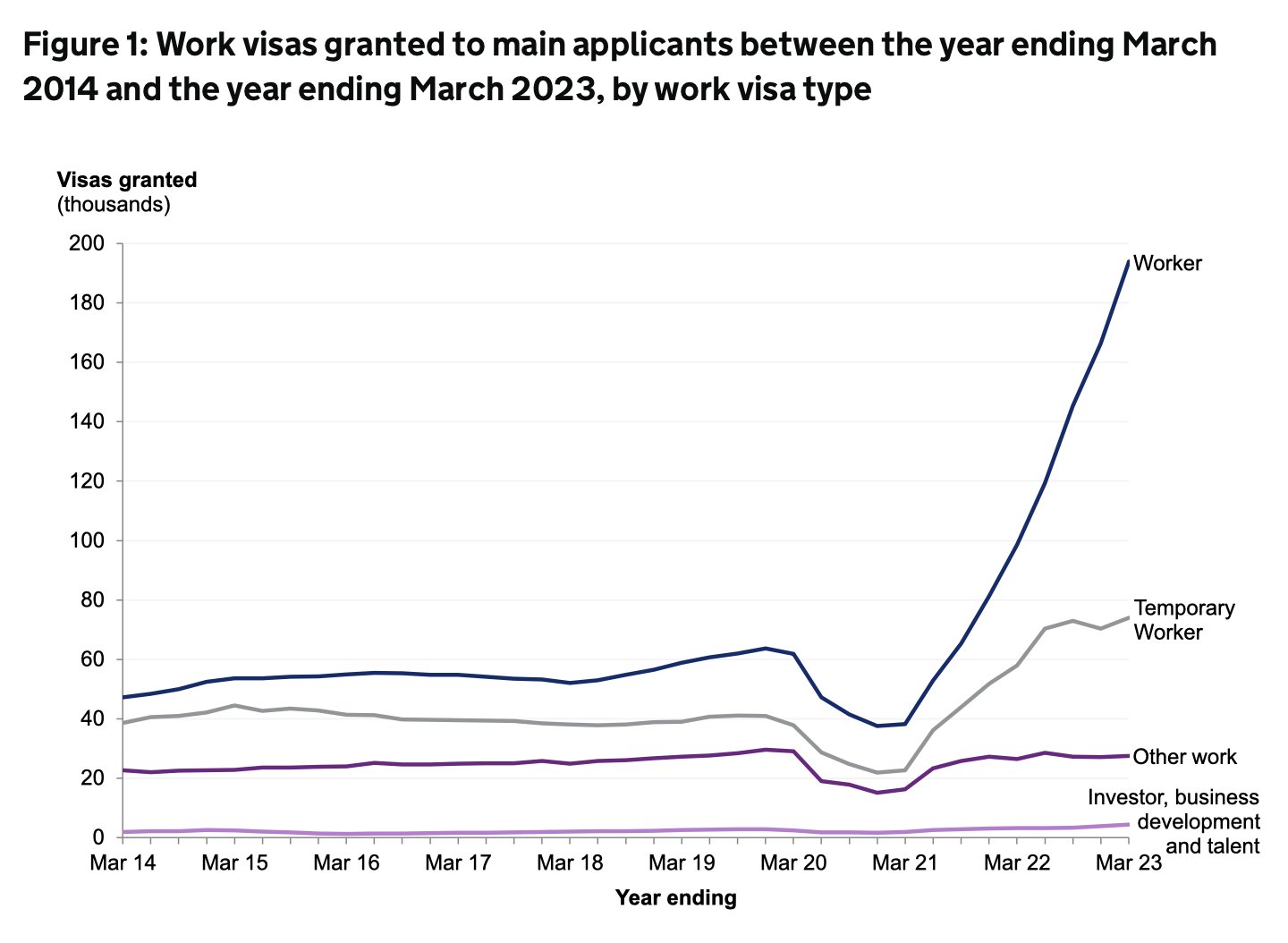

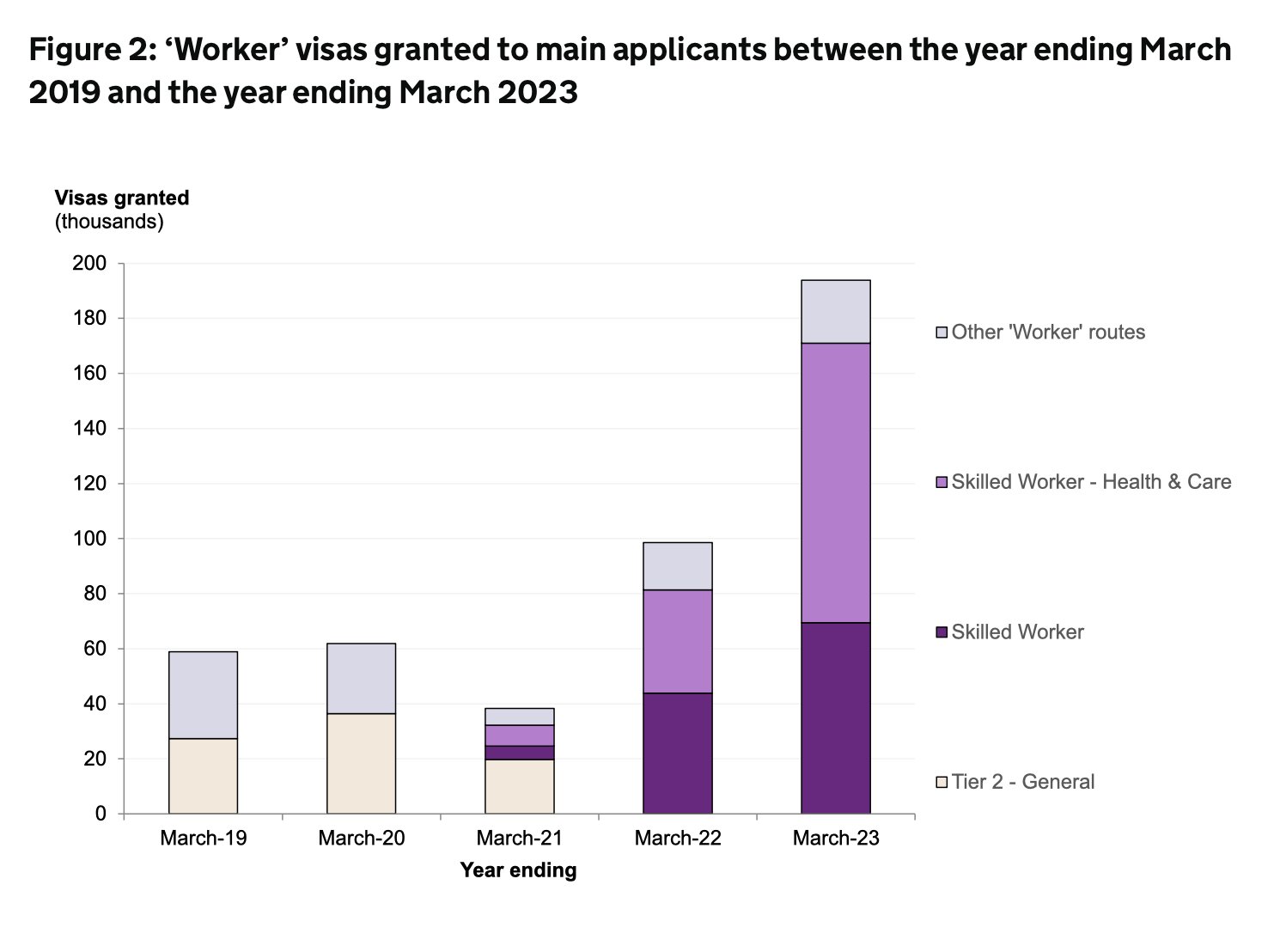

Work visas were up around 61% to 300,000, and that is before dependants are counted. The Home Office breaks these visas down into worker, temporary worker, other work and fancy visas. Not really: investor, business development and talent.

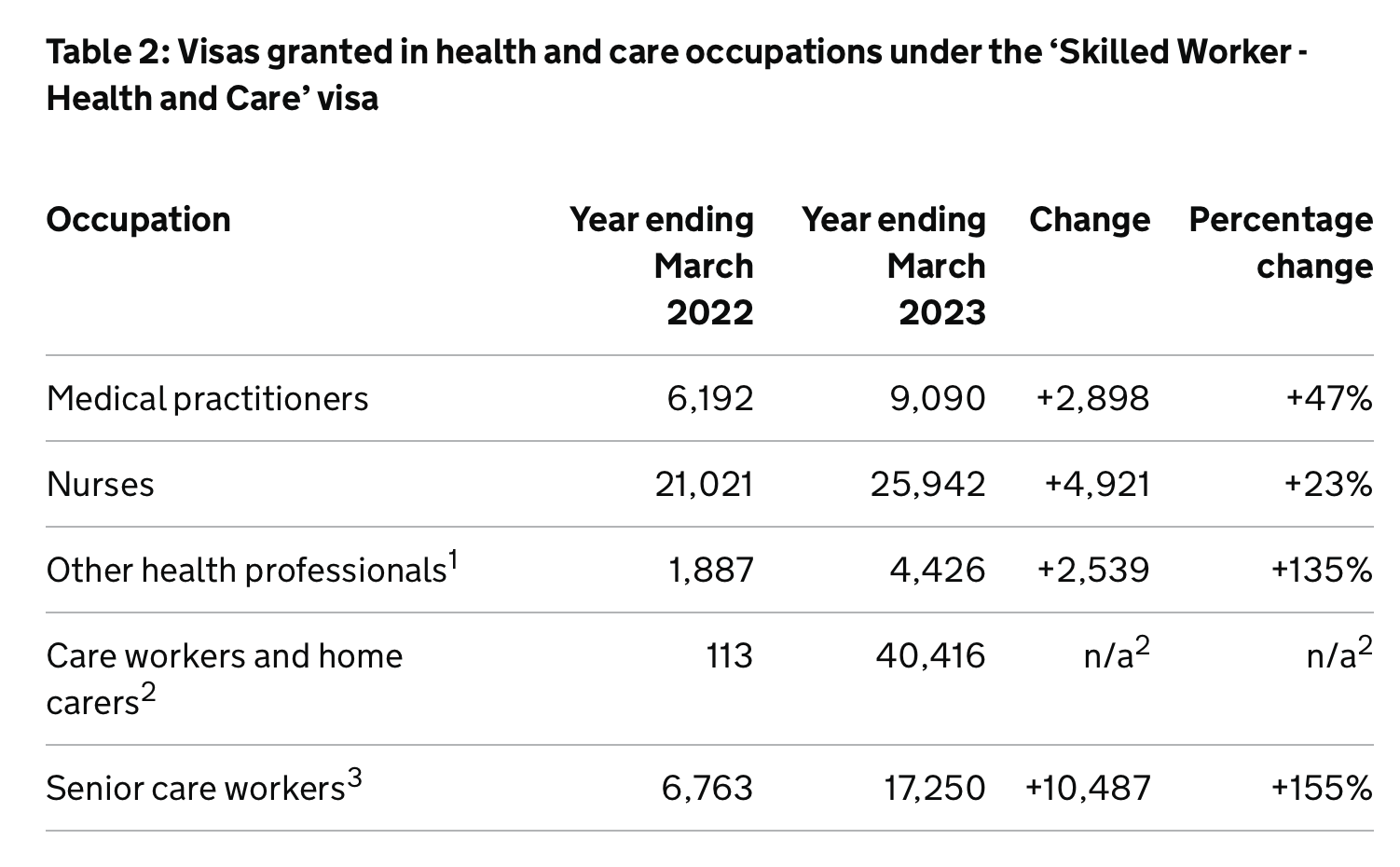

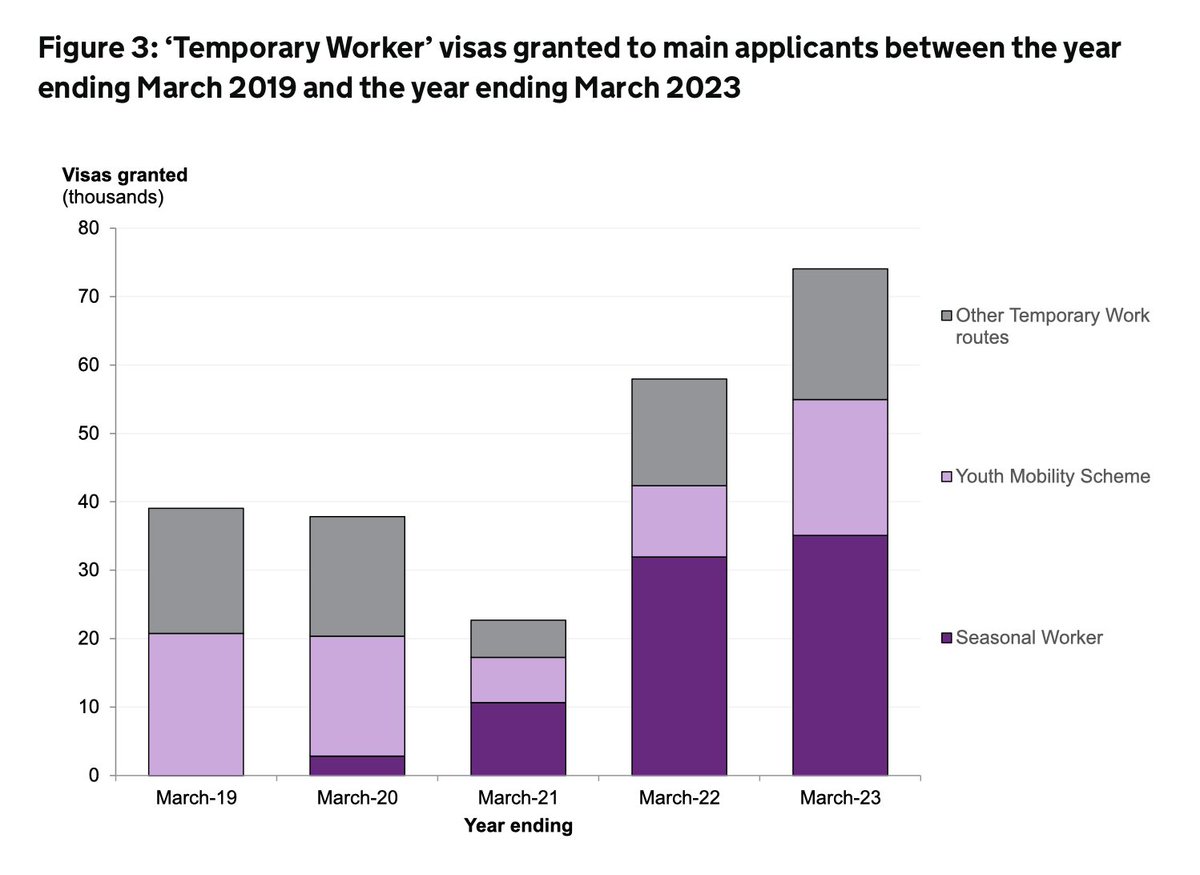

The overall increase is mainly due to a big increase in skilled worker visas. That in turn is due to a big increase in health and care visas. That in turn is due to a big increase in care workers. There were basically zero of these in 2022 and 40,000 in 2023. There was also an increase in the number of youth mobility visas issued, although nothing particularly dramatic.

There were very few of the ‘brightest and best’ type visas issued:

- 64% rise (+1,333) in ‘Global Talent’ visas to 3,404 grants

- 25% rise (+82) in ‘Innovator’ visas to 404 grants

- 14% fall (-68) for ‘Start-Up’ visas to 421 grants

Nearly 20,000 overseas domestic worker visas were issued. That’s down compared to pre-pandemic, apparently, but I confess I had not realised so many of these problematic visas were issued.

Where do these workers come from? It depends on the visa type.

- Skilled workers: India, US, Philippines.

- Health and care: India Nigeria, Zimbabwe.

- Agricultural workers: Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

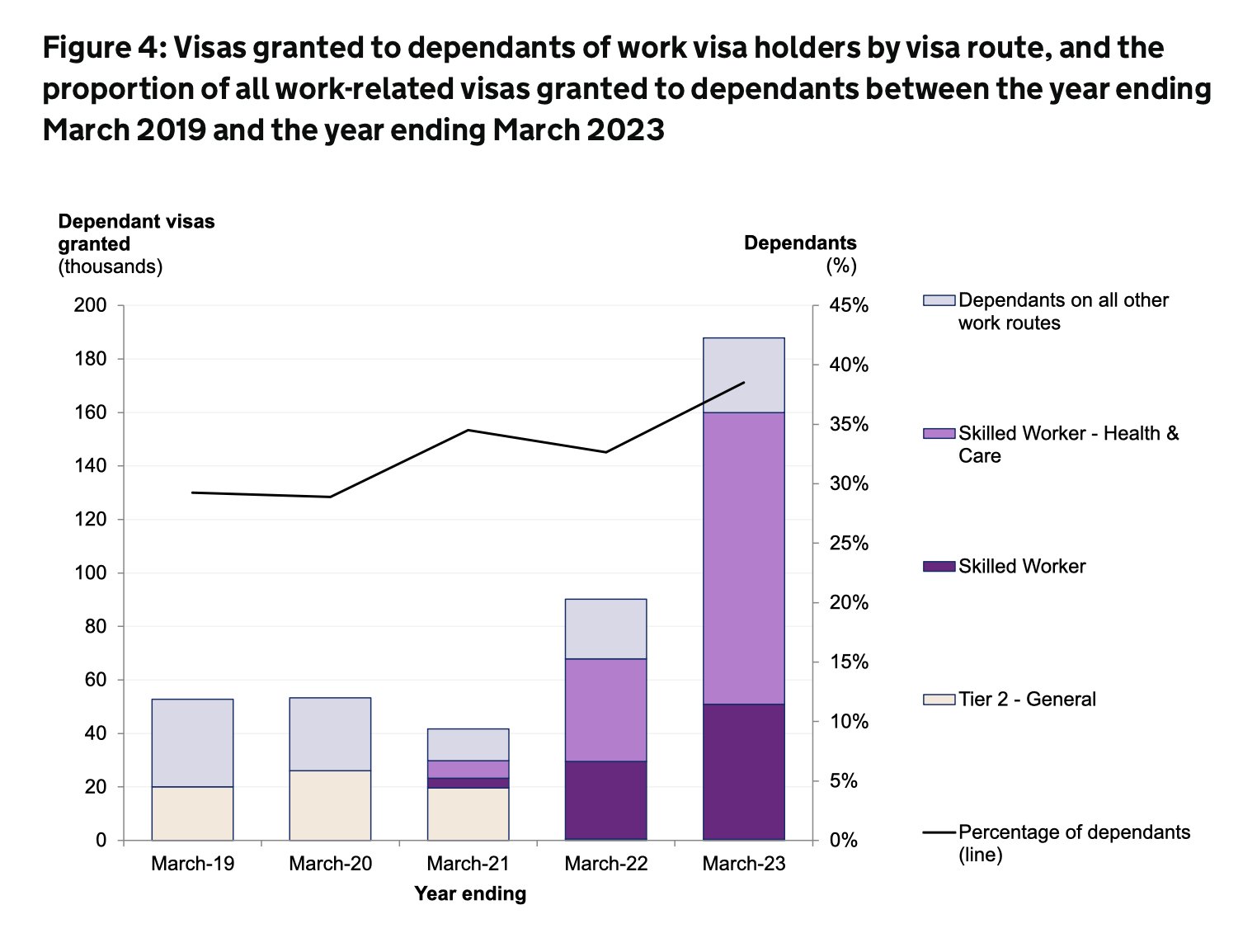

Skilled workers generally won’t come unless they are allowed to bring their families, so quite a lot of dependant visas were also issued. The absolute numbers increased a lot, and the percentage compared to main applicants also increased a bit too.

Students

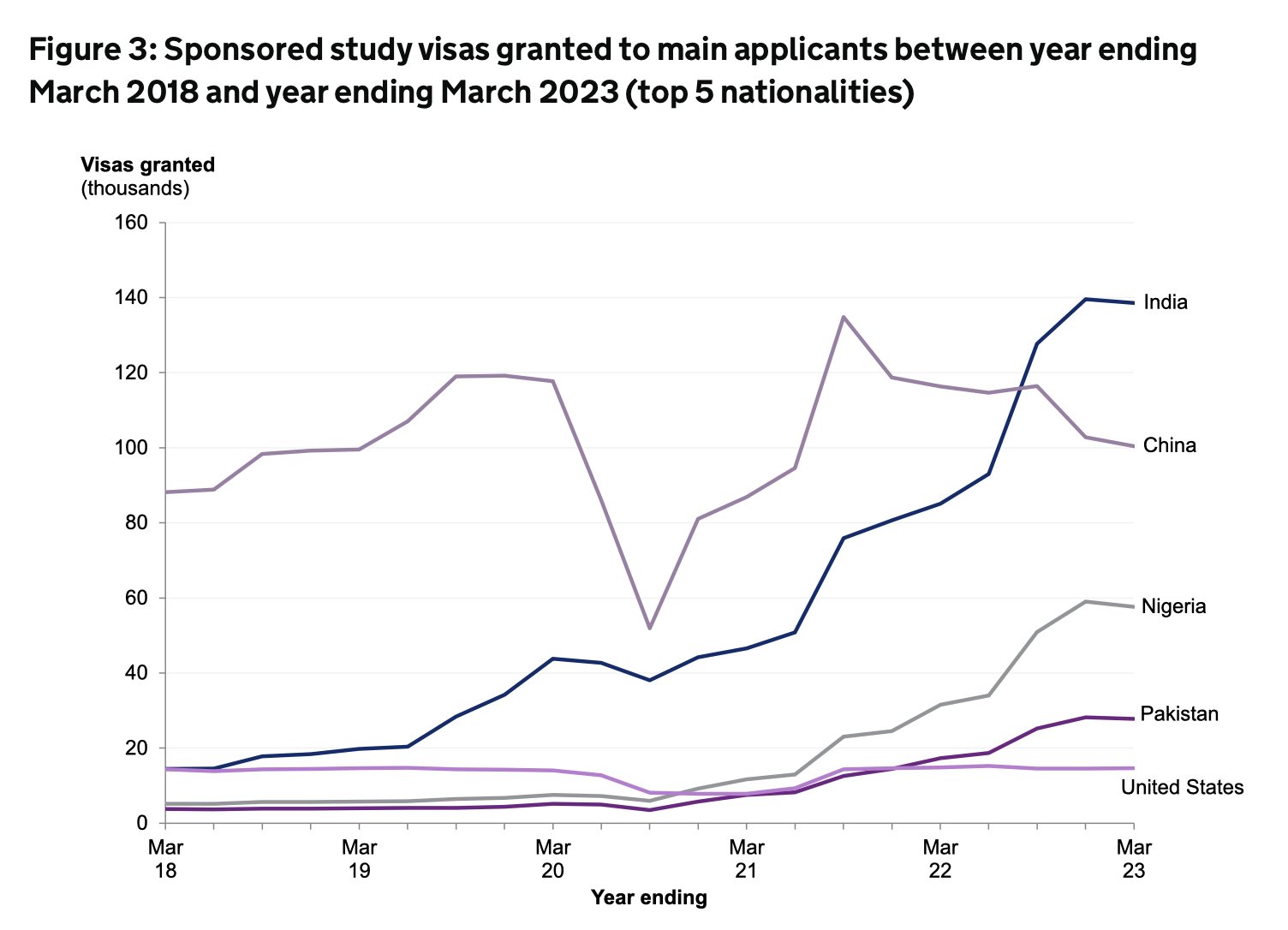

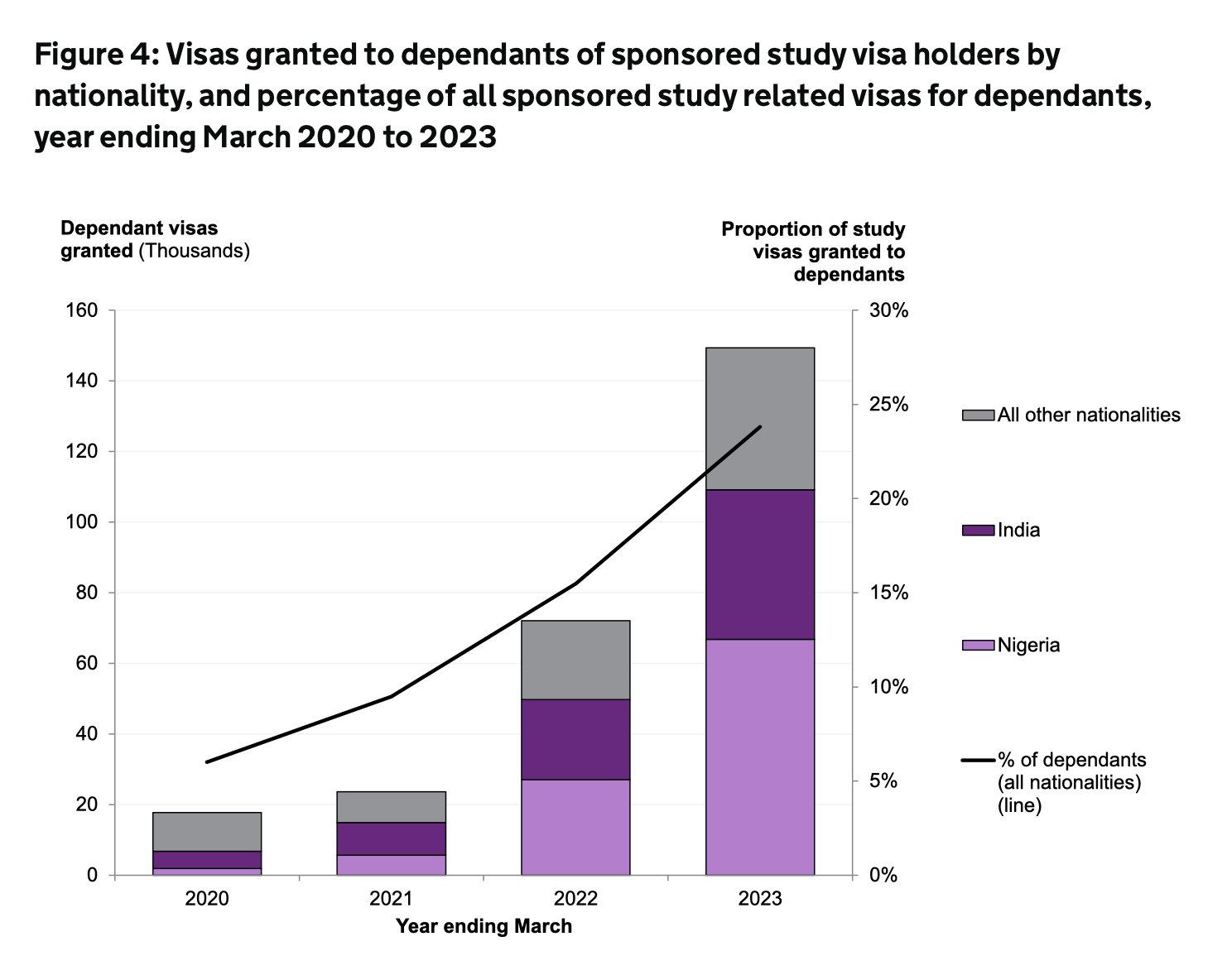

Student visas were up 22% to 480,000. The main countries of origin were India, China, Nigeria, Pakistan and the US. Another 150,000 visas were issued to student dependants. 73% of these dependant visas were to Nigerians and Indians.

Family, settlement and citizenship

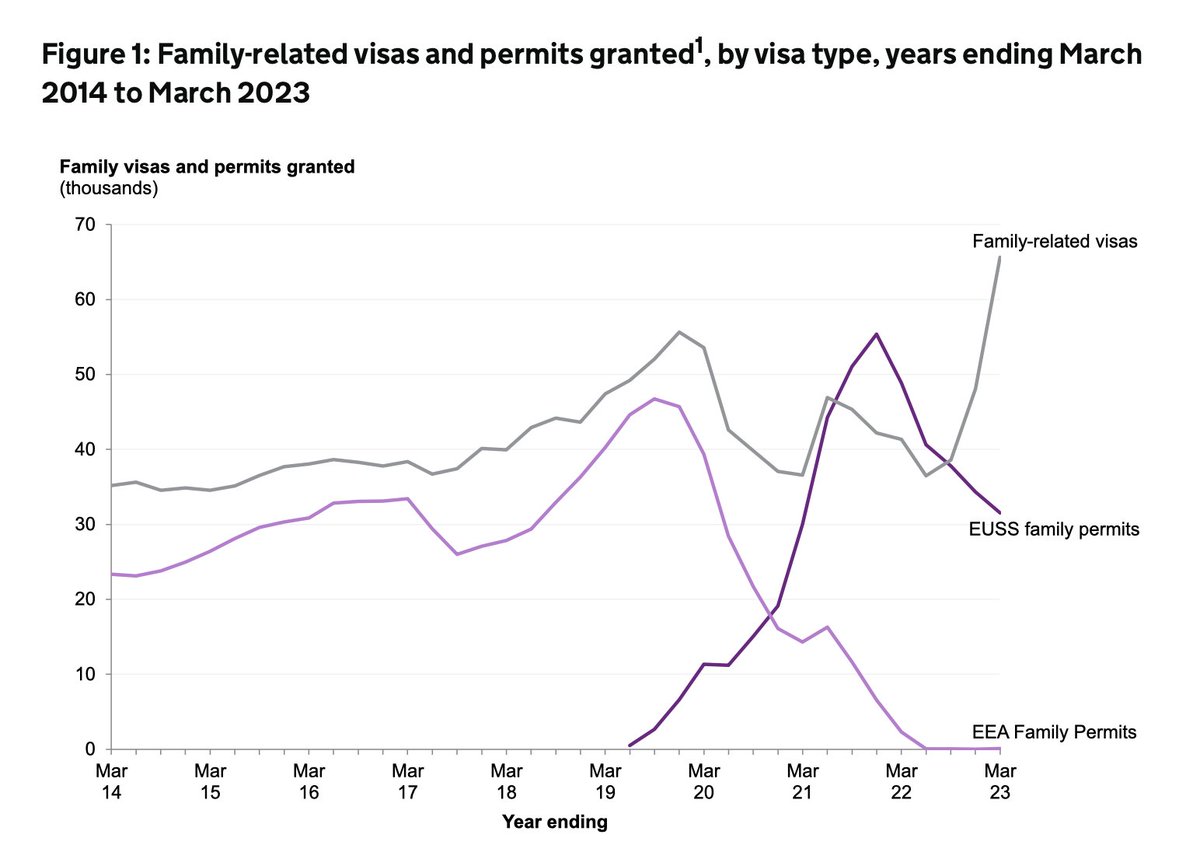

Spouse and partner visas increased quite a lot, but that might be because EU citizens now have to use this visa category. EEA family permits no longer exist and EUSS family permits are down a lot.

The main nationalities of family visa recipients were Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, US and Nepal.

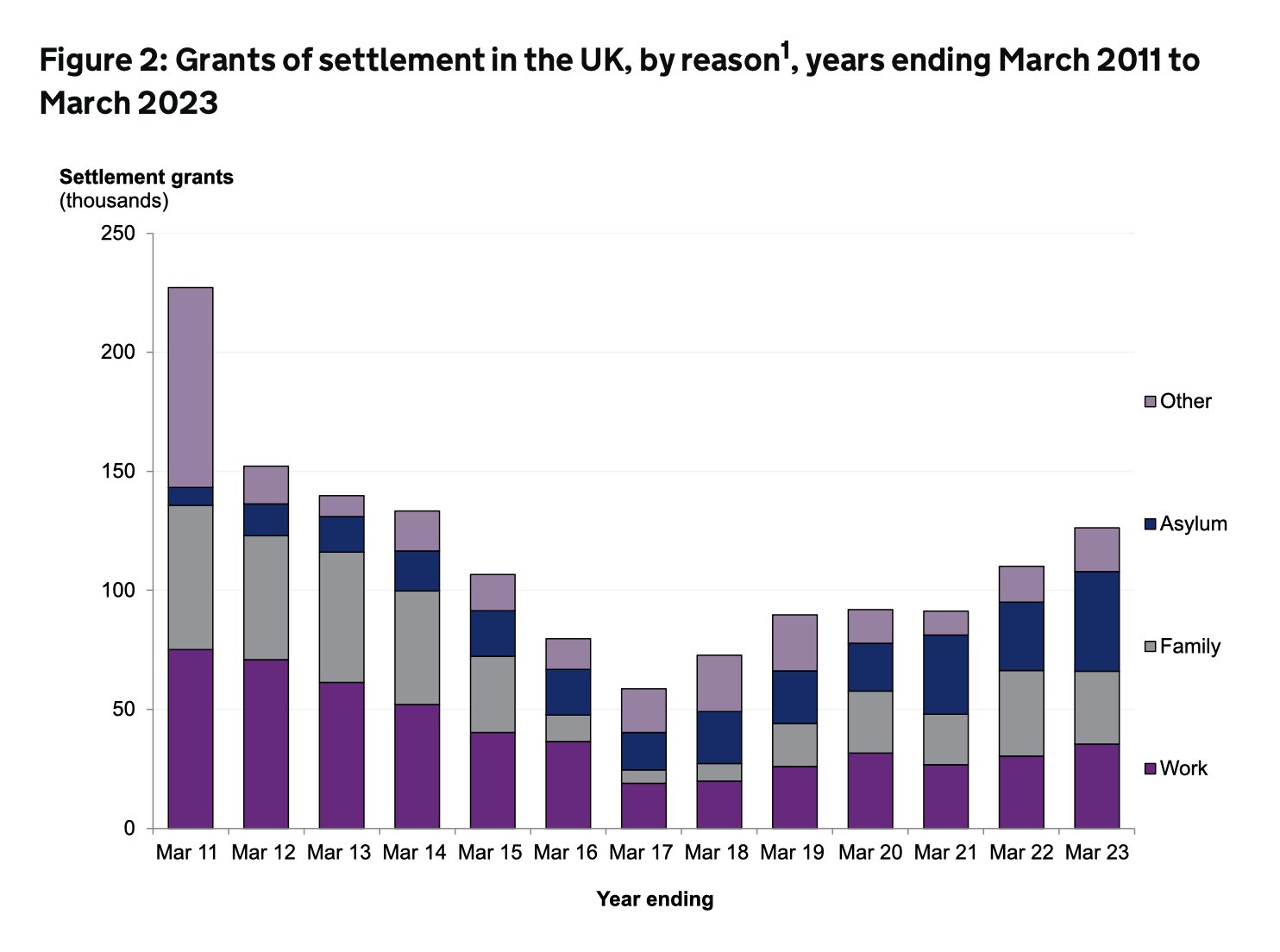

Grants of settlement were up. I’m a bit surprised such a high percentage of these are to refugees. It begs the question of what has happened to the workers and family members who entered five years previously and were now eligible for settlement. I haven’t compared the stats from that period but it could be an interesting exercise.

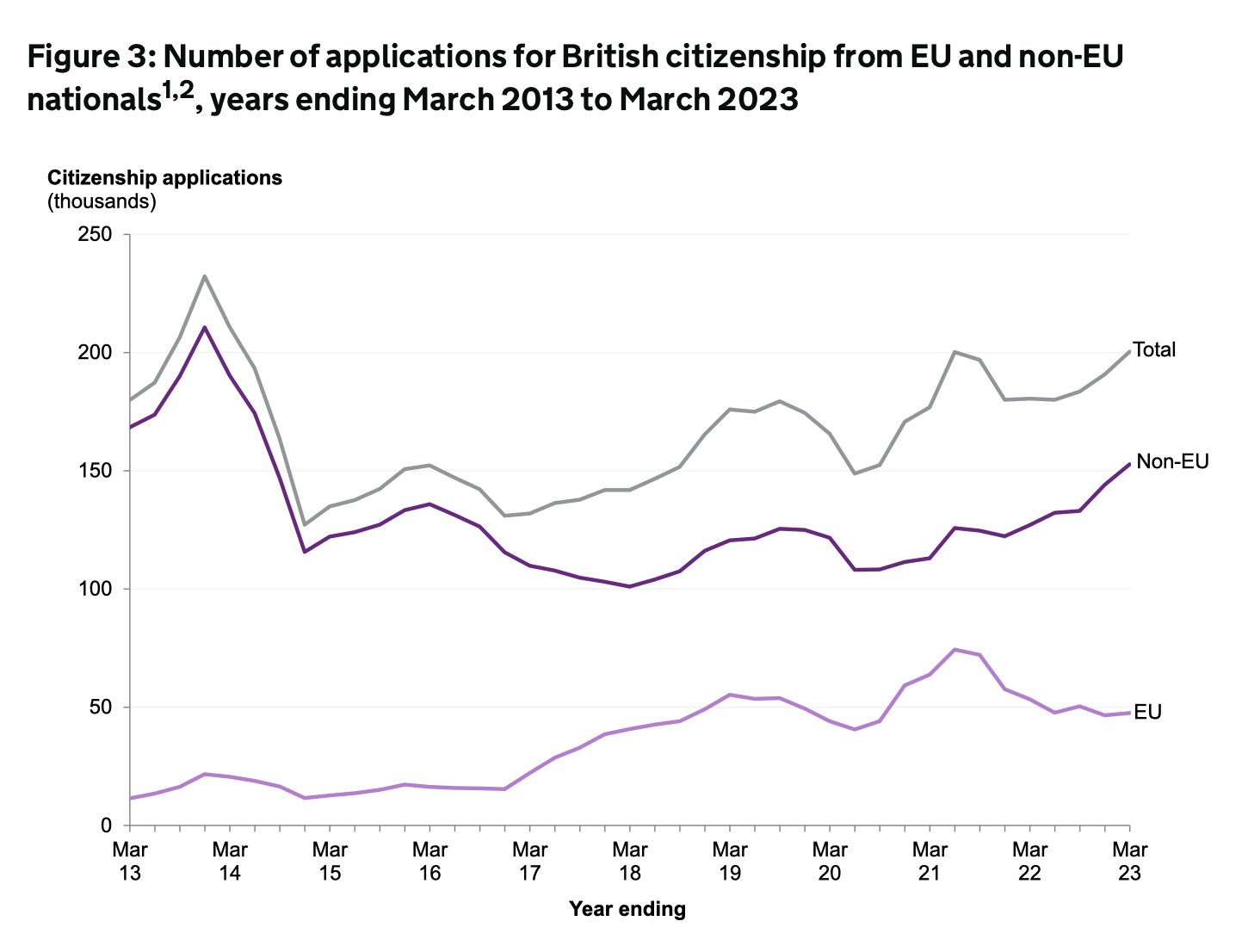

Citizenship applications were also up, by 11%. But applicants by EU citizens actually fell compared to a peal in 2021.

There were 180,000 grants of citizenship. 130,000 were naturalisation of adults. 50,000 were registration, which is mainly children.

Overall, visas issued were up quite dramatically. Most of the students will eventually return, so will eventually show up on the emigration side of the net migration figures in future years. Most workers will presumably qualify for settlement then citizenship. The vast majority of refugees who arrived before 7 March 2023 will also eventually qualify for settlement, as far as we can see, although they will be on a very prolonged ten year path.

But the modest increases in settlement and citizenship we can see in the latest stats pose the question of what happens to migrants once they come to the UK. In a functioning system, migrants come for a short time and return or would be helped to integrate in the long term. The United Kingdom’s immigration laws make that harder rather than easier. That will be one of the recurrent issues I look at over on We Wanted Workers…

SHARE

One Response