- BY cjmckinney

Immigration appeal waiting times rise 13%, now take a year on average

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

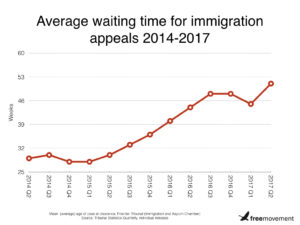

The average immigration appeal takes almost 12 months to be resolved, up 13% on the same period last year.

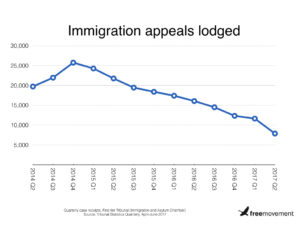

This is despite the fact that less than half as many people now have the chance to challenge Home Office decisions. The number of appeals handled by the immigration tribunal has fallen from around 20,000 to 8,000 – a startling 60% fall – since the Immigration Act 2014 was passed.

Appeal waiting times continue to rise

Immigration and asylum appeals at the First-tier Tribunal took 51 weeks to be resolved in April-June 2017 – the latest period for which data is available – according to the Ministry of Justice. That represents an increase of seven weeks on the same period last year.

Looking across the whole financial year, first-tier appeals took three months longer in 2016/17 than they did in 2015/16.

There is a silver lining in the figures for asylum appeals specifically. Cases took 29 weeks to be cleared in April-June 2017, compared to 38 weeks in April-June 2016.

We can no longer usefully compare some other categories of appeal. For example, on the face of the statistics “family visit visa” appeals appear to take 194 weeks! But this category, along with “managed migration” and “entry clearance”, is being phased out. There were only four family visa appeals decided in the last quarter, and zero new receipts, so the average is at this point meaningless.

All appeals are now being consolidated under “human rights”, “EEA free movement” or “other”, along with the existing “asylum” heading. These are the only relevant headings to consult in the data.

This change means that only the overall average and the consistent “asylum” category of appeals can be compared over time. Practitioners and clients will find plenty to be concerned about even without a point of reference. EEA free movement appeals take 45 weeks, for example.

| All | 52 weeks |

| Asylum/protection | 29 weeks |

| Human rights | 60 weeks |

| EEA free movement | 45 weeks |

| Other (including deportation and deprivation of citizenship) | 36 weeks |

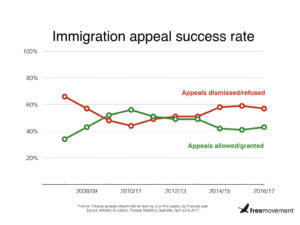

This would be one thing if appeals were a frivolous shot in the dark. But they in are, in fact, an integral part of the immigration system’s decision making. Almost half (47%) of appeals decided by a First-tier Tribunal judge were allowed in the most recent quarter.

It remains to be seen whether this roughly 50/50 split will be sustained through the rest of the year. If so, it would represent a return to the situation that prevailed a few years ago.

Appeal rights eroded

The First-tier Tribunal received 7,800 cases between April and June 2017. In the same quarter three years ago, it was 19,700. That represents a decline of 60%.

To put that in context: the fall is in the same ballpark as the drop-off in employment tribunal cases following the introduction of fees there. Employment tribunal fees, which severely restricted access to justice in that field before the Supreme Court struck them down last summer, reduced caseload by 68%.

Receipts have now fallen for the last ten quarters in succession.

Upper Tribunal receipts have also fallen over the period, although the trend is not steady.

What has changed since 2014/15? The Immigration Act 2014, and its 2016 successor, have been brought into force. These have reduced appeal rights and heralded a policy of “deport first, appeal later” (although this summer’s Supreme Court judgment in Kiarie and Byndloss places severe restrictions on the lawful use of that approach, at least in the short term).

As the number of appeals plummets, there has been a consequent fall in the number of cases outstanding (now a mere 43,400). While restricting avenues of appeal is one way to give the appearance of a more efficient judicial system, resourcing that system adequately could achieve much the same thing, with the added bonus of respect for the rule of law.