- BY John Vassiliou

Illegal working fines aren’t working

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat follows is a real case from my practice. Names have been changed.

My clients (let’s call them Mr and Mrs Restaurant) have run a restaurant since 2004. Their establishment is beloved in the local community, especially amongst families. It feels like a real community hub, and in amongst the churn of opening and closing beauty salons, nail bars and hairdressers, this restaurant has been a comforting constant in the neighbourhood.

Around 5pm one late spring afternoon, just as early diners were placing their orders and getting settled at their tables, the door swung open and a group of Immigration Enforcement officers stormed in, equipped with stab-proof vests. One can never be too careful around families eating their supper.

Immigration Enforcement were investigating a report about illegal workers. Mr and Mrs Restaurant were confident a mistake had been made and the officers appeared sympathetic to their situation. It turned out however that one staff member had given false details when they hired him, and another had recently let his visa expire.

The Restaurant family were under the mistaken but not entirely unreasonable impression that because the staff had all provided valid National Insurance numbers there was no issue with their right to work. Naturally only those with a right to work would have a National Insurance number and if there were any issues HM Revenue and Customs would surely have been on to them already. One can see the logic in their reasoning.

The officers reassured Mr and Mrs Restaurant that all would likely be OK, especially because they had been so compliant with the investigation, but, ultimately, it was not up to them what happened next; they would report to the main office in Manchester where things would be taken forward. And so a £40,000 civil penalty notice plopped through the letterbox a few weeks later.

The reason for the penalty? Employing two illegal workers who did not have the right to work in the UK and failing to provide a statutory excuse against such a civil penalty notice.

The law on illegal working penalties

Section 15 of the Immigration, Nationality and Asylum Act 2006 sets out the circumstances in which a civil penalty can be issued:

(1) It is contrary to this section to employ an adult subject to immigration control if—

(a) he has not been granted leave to enter or remain in the United Kingdom, or

(b) his leave to enter or remain in the United Kingdom—

(i) is invalid,

(ii) has ceased to have effect (whether by reason of curtailment, revocation, cancellation, passage of time or otherwise), or

(iii) is subject to a condition preventing him from accepting the employment.

(2) The Secretary of State may give an employer who acts contrary to this section a notice requiring him to pay a penalty of a specified amount not exceeding the prescribed maximum.

I’ve emphasised the word “may” to highlight the discretionary nature of these penalties, for reasons I will come back to later.

(3) An employer is excused from paying a penalty if he shows that he complied with any prescribed requirements in relation to the employment.

(4) But the excuse in subsection (3) shall not apply to an employer who knew, at any time during the period of the employment, that it was contrary to this section.

If an employer has conducted the appropriate right-to-work checks and retained the appropriate evidence, the employer will have an excuse not to pay any penalty issued. This becomes irrelevant if the employer knowingly employed someone who did not have the right to work.

The 2006 changes sowed the seeds of what we now call the hostile environment, shifting the onus for immigration control from the state to the individual. Mr and Mrs Restaurant missed this memo. The couple had researched their employment obligations in 2004 when setting up their business, and got on with it. They had never sought advice on immigration-related duties as employers and held the reasonable view that someone would notify them of any fresh legal obligations.

How is the penalty calculated?

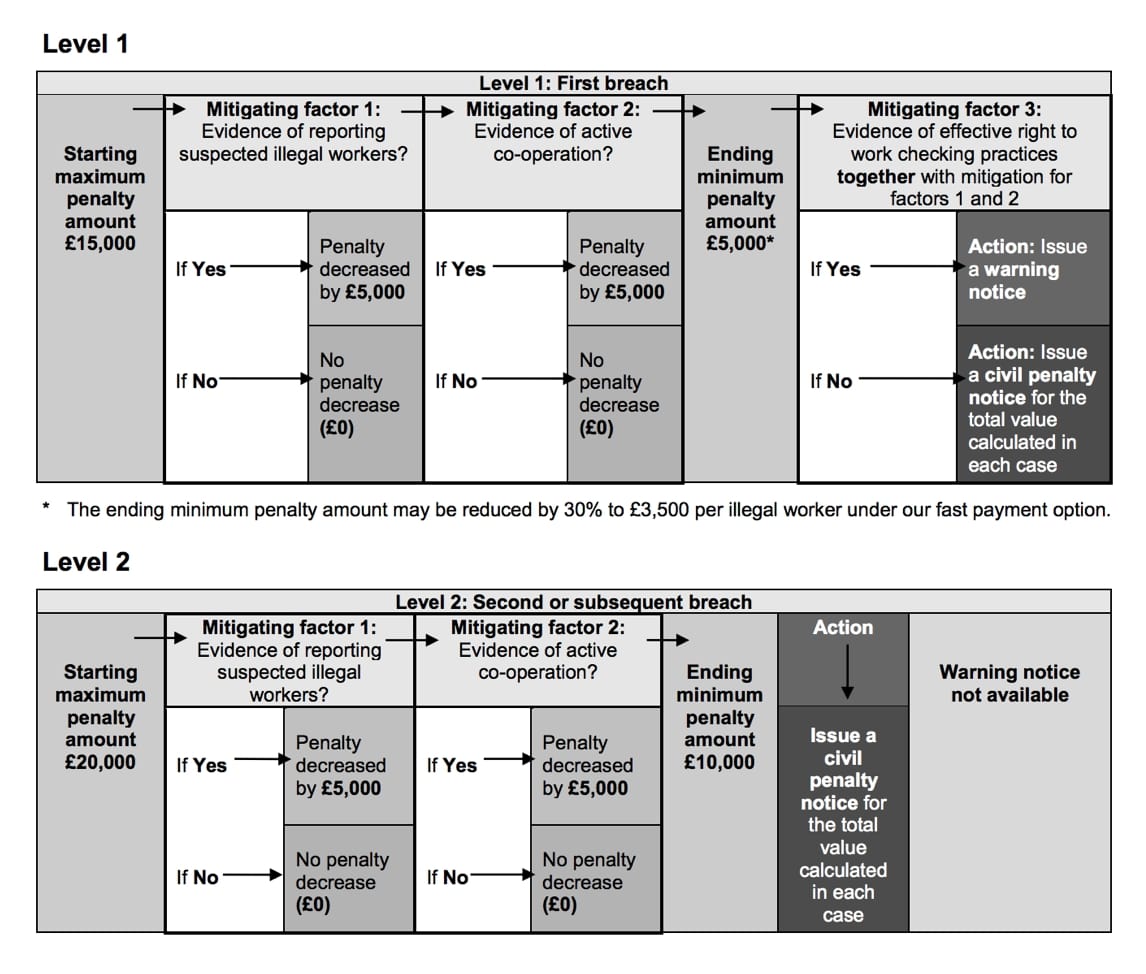

Assuming the employer has not been found to have been employing illegal workers in the past three years, the starting penalty is £15,000 per illegal worker. (If it is a second offence, the starting point is £20,000.)

This can be reduced if there are mitigating factors.

If the employer self-reported the illegal working, Home Office will knock off a measly £5,000 per illegal worker (if anyone else wants to join me in bashing their heads off their desks after reading this, misery loves company)

If the employer actively cooperated with the investigation, a further £5,000 can be lopped off.

If the employer ticked both of the above boxes, AND provided evidence of effective right-to-work checking practices, then they might get off with a warning and no penalty. If not, they will be issued with a penalty.

Fast payment of the penalty will result in a further 30% reduction. This means that the final penalty will fall somewhere between £3,500 – £15,000 per illegal worker, but this necessarily requires fast access to a large amount of cash. Payment in instalments over a number of years is permitted but opting for this takes the 30% discount off the table.

A handy flowchart is buried on page 9 of the Home Office’s codes of practice for those who prefer a visual representation.

Mr and Mrs Restaurant’s penalty

Mr and Mrs Restaurant were initially landed with a frankly terrifying £40,000 penalty. That is the raw, unreduced sum of £20,000 per head multiplied by the number of illegal workers (two). To nobody’s surprise, the Home Office abacus had been malfunctioning and the caseworker had forgotten to apply both the £5,000 per head reduction for this being the restaurant’s first breach of the law, and the further £5,000 per head reduction for active co-operation.

It took months of correspondence between the restaurant and the Home Office to bring this down to the correct penalty of £10,000 per worker. From there, if Mr and Mrs Restaurant elected to pay in full within 21 days, they would benefit from the 30% faster payment reduction, meaning a final fine of £14,000.

That is still an eye-watering amount for a small family-run business. The news of this civil penalty crushed them. Not many people have a spare £14,000 – £20,000 to throw around, and Mr and Mrs Restaurant were no exception. They lodged an objection, taking time to carefully explain that they had no way of knowing about these new obligations and had no idea they had been breaking the law. They explained that this type of penalty would cripple their business and force them to make tough choices in order to continue being able to pay their staff.

Sadly they acted without the benefit of legal advice. The Home Office did not uphold their objection. Their local MP asked the immigration minister to intervene but there was no such luck. All he managed to elicit was a letter from the team in Manchester upholding the penalty and stating:

We accept that [the employer] did not intentionally employ the two illegal workers but the civil penalty scheme is designed to encourage employers to comply with their legal obligations.

By the time they did seek advice, they were too weary to fight in the courts or in the press. In the end Mr and Mrs Restaurant had to remortgage their home to pay the Home Office.

Punishment, not prevention

Take a moment to read that line from the Home Office’s response again. Fellow lawyers will be familiar with the old adage that ignorance of the law is no defence. But the whole point of these eye-wateringly high fines is apparently to discourage people from breaking the law, or, as the Home Office puts it, “to encourage employers to comply with their legal obligations”.

Is the Home Office achieving its goal of compliance with legal obligations if small businesses such as this are unaware of them? During Theresa May’s tenure as Home Secretary, the government gleefully doubled the civil penalty from £10,000 to £20,000. But there was no accompanying publicity drive to ensure that businesses are aware of this regime and their duties.

What use is doubling down on punishment when people aren’t aware of the crime? It is no wonder that the immigration inspector recently concluded that, when it comes to preventing illegal working, “the Home Office’s efforts are not really working”.

The civil penalty scheme in Mr and Mrs Restaurant’s case failed to prevent illegal working. What it did do is cause a huge amount of emotional and financial distress for a hard-working couple. Sure, they won’t make the mistake of not thoroughly checking an employee’s documents next time, but the cost of the fine was so high that they are now considering shutting up shop completely, having been drained of cash and the will to go on. Their staff and their community will sorely miss them.

Contrast this experience with the archetypal nail bar. In my area, it is well known that certain nail bars regularly employ workers who do not have permission to work. And the Home Office knows this too.

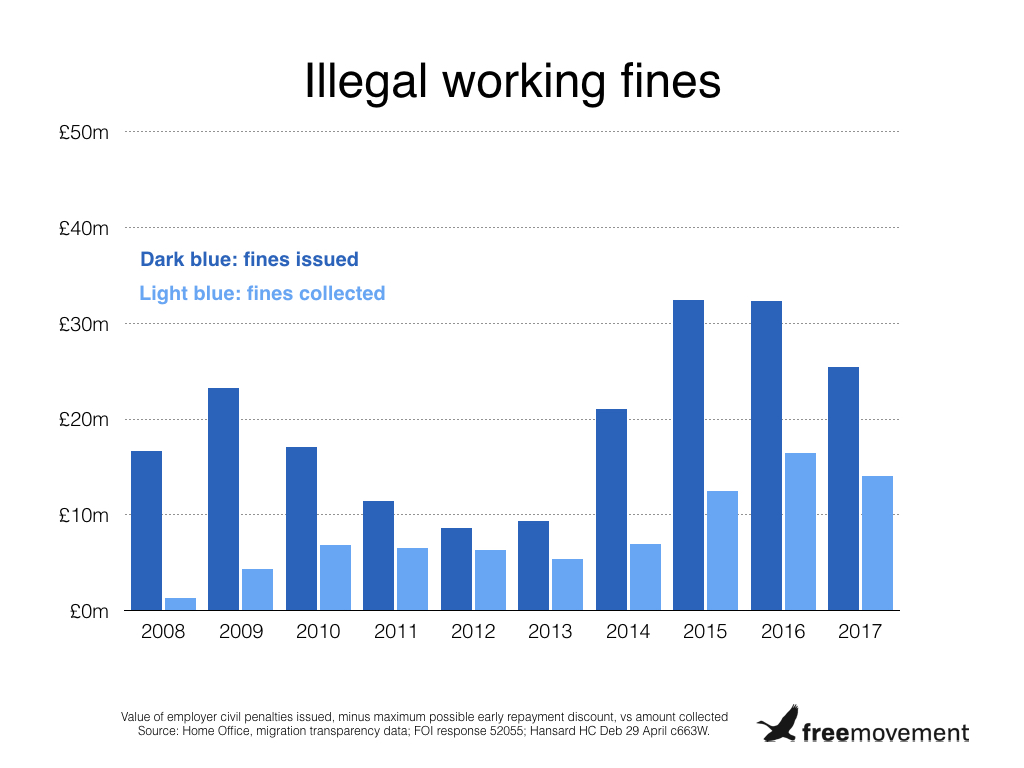

Immigration Enforcement regularly busts these places and issues penalty notices. But the owners immediately shut up shop and disappear, or declare themselves bankrupt, and six months later a new, similarly-named venue opens up just down the road. This phoenix operation has a new owner (on paper at least) and the cycle of employing undocumented or trafficked workers continues. Such evasion, combined with successful reviews and appeals, means that the Home Office collects only about half of all illegal working fines issued.

How can the system be improved?

A nationwide information campaign

If the objective is prevention of illegal working, the first step must be a comprehensive information campaign. The Home Office can and should collaborate with HM Revenue and Customs to send information to employers setting out their duties in relation to right-to-work checks. Prevention is the best medicine, and if Mr and Mrs Restaurant had been armed with the knowledge that they needed to check their staff members’ visas regularly, they would have done so.

Don’t treat discretionary penalties as mandatory

Remember that word “may” that I emphasised earlier on? The Secretary of State may give an employer a penalty. It’s discretionary, not mandatory, to issue a penalty. In Mr and Mrs Restaurant’s case there was no acknowledgment of that discretion, and no willingness to treat this as anything but a mandatory penalty.

There is definitely room for improvement here. Someone sufficiently senior could have reviewed this particular case, interviewed the employers, and considered whether it was in fact in the public interest to issue a £20,000 penalty against them.

Others may take a different view, but I don’t think it was appropriate in this case. Both offending workers had been apprehended and there was no risk of continuing harm. A stern warning to the employer would have been enough to ensure future compliance with right-to-work checks, perhaps with an unannounced follow-up inspection some months later.

Incentivise self-reporting

Earlier I commented on the absurdity of the £5,000 reduction for those who self-report. This is not an incentive to report a breach. It’s the exact opposite: an incentive to cover up that breach and avoid the rest of the penalty.

Those who self-report for the first time and who have had no past breaches ought to be considered for a discretionary warning in lieu of a penalty for having the honesty to come forward.

Make the penalties affordable

A quick glance through the Home Office’s latest stats on civil penalties will reveal what is already common knowledge amongst immigration professionals: the vast majority are levied against small businesses that operate on tight margins in cash-heavy sectors such as the food and beverage industry, nail bars, and car washes. Similarly, the immigration inspector’s report last year found that almost half of Immigration Enforcement raids were to restaurants and takeaways.

Rarely can such a business sustain a massive civil penalty. More likely than not, they simply declare themselves bankrupt. This means nothing is recovered by the Home Office.

Perhaps if the penalties were less aggressive, there would be more chance of businesses actually paying them, and of working with the Home Office to remain in business and reform their practices for the future.

A version of this article has been submitted by the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association to the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration in response to a recent call for evidence.

SHARE