- BY Colin Yeo

How does the asylum ‘white list’ work and what does the government plan to change?

Table of Contents

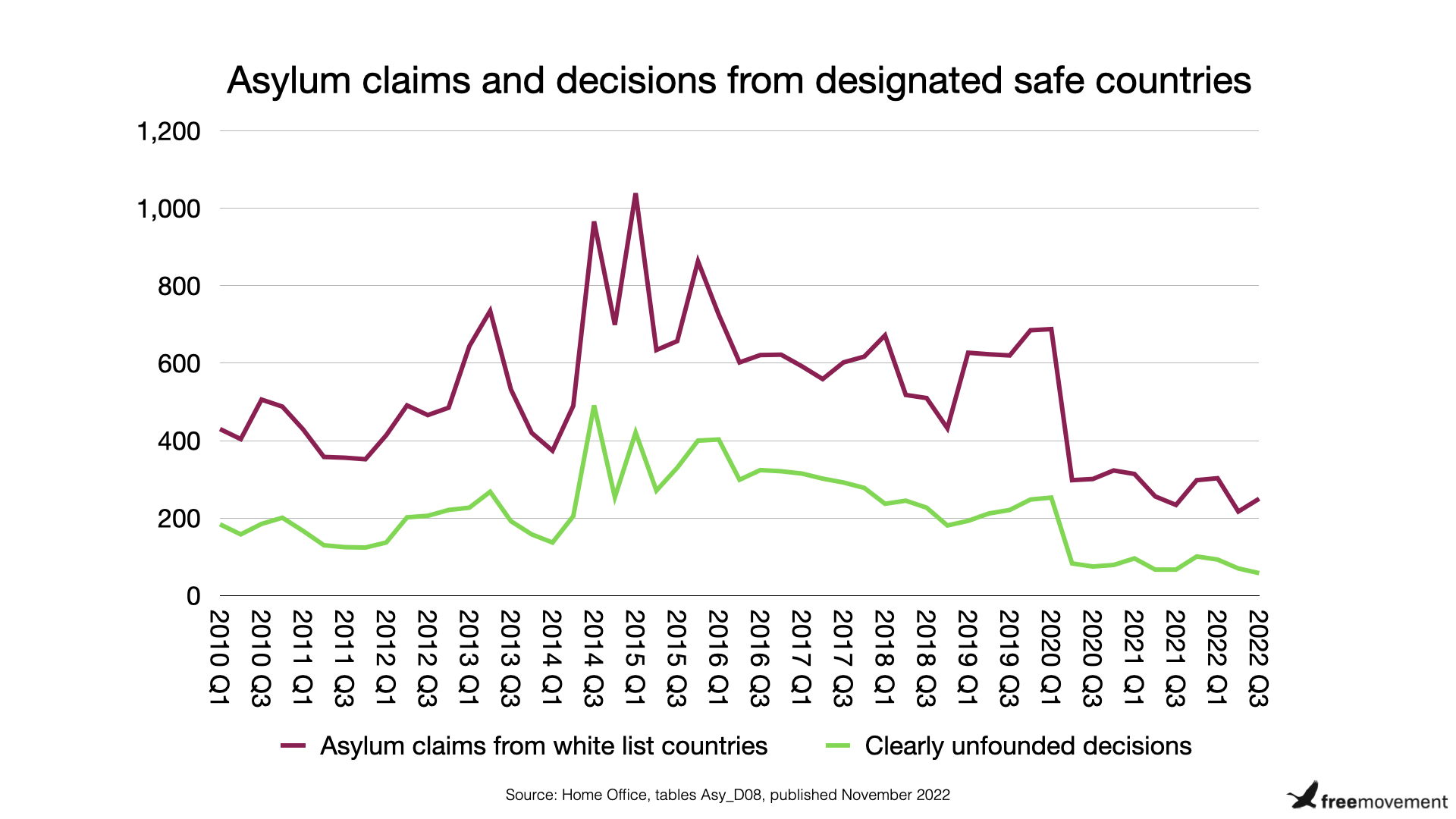

ToggleThe idea of a ‘white list’ of countries which are presumed to be safe and whose nationals will be swiftly returned is not a new one. In fact, it has been a feature of British law since section 2 of the Asylum and Immigration Act 1996 came into effect. The latest immigration statistics show that 1,068 asylum decisions were made in the last year relating to people from designated safe countries, and that around one third of those asylum claims were decided to be clearly unfounded on this basis. The Times today reports that the Home Secretary, currently Suella Braverman, is looking to ‘resurrect’ this list.

The reality is that the list is currently as operational as the rest of the asylum process. It still exists in theory but decision making has slowed down so much in recent years under Home Secretaries Patel, Braverman, Shapps and Braverman that there are very few white list decisions being made, just as very few other asylum decisions are being made. At the moment, if a person claims asylum from a white list country, they will be waiting years to receive a decision.

What seems to be new, from the report in The Times, is that the Home Office is contemplating fast-tracking claims from white list countries. This is how the list used to operate back in the 2000s. Except that back then the government provided free legal advice to those who were detained for fast track processing. I should know, I was one of the lawyers giving the free legal advice. My first legal job was giving advice at the Oakington detention centre, a converted former barracks near Cambridge, to fast tracked asylum seekers from white list countries. The ‘Oakington process’ as it was known was challenged at the European Court of Human Rights. The government won in the case of Saadi v United Kingdom (App no 13229/03), in part because free legal advice was provided. Trying to resurrect that process but without any lawyers is very likely to lead to a successful legal challenge.

Summary: TL;DR

There is a list of countries that are presumed to be safe. If a person from one of those countries claims asylum, their claim will normally be ‘certified’ by a Home Office official as being ‘clearly unfounded’. The person has a chance to argue that their country is not safe for them even if it is safe for others. If the person’s claim is certified, the person has no right of appeal. There used to be a right of appeal from outside the country after removal, but the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 scrapped even this safeguard. If a person’s claim is certified and they therefore have no right of appeal, they can attempt to judicially review the decision to certify their claim and that judicial review will be heard from within the UK.

How does the current ‘white list’ work?

Different versions of a ‘white list’ approach whereby certain countries are presumed to be safe have been in force continuously since 1996. The current applicable legislation is primarily section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002, which has been amended several times. You can see the full list of designated safe countries by clicking the link above. Since 2004, the list can specify a safe region of a country or a safe type of person, such as men or women. But for present purposes, yes, Albania is on the list. And has been since 1 April 2004.

If a person claims asylum and they come from a country on the list, their asylum claim will be presumed to be ‘clearly unfounded’ and their claim will be ‘certified’ as such (no actual certificates are handed out). The legislation states that where a person comes from a country on the list, an official from the Home Office shall (i.e. must) certify a claim ‘unless satisfied that it is not clearly unfounded.’ This is what lawyers call a rebuttable presumption: the person concerned can argue that the presumption should not be applied in their case. So, what does ‘clearly unfounded’ mean and how can the presumption be rebutted?

The leading case is ZL and VL v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2003] EWCA Civ 25. Sending a refugee back to be persecuted in their home country is obviously a very bad thing to do, and there are therefore safeguards.

What does ‘clearly unfounded’ mean in asylum claims?

An asylum claim has to have essentially no chance of succeeding in order for it to be considered clearly unfounded. In ZL and VL the Court of Appeal ruled that if an asylum claim “cannot on any legitimate view succeed, then the claim is clearly unfounded” (para 57). Or, to put it another way, “[i]f on at least one legitimate view of the facts or the law the claim may succeed, the claim will not be clearly unfounded” (para 58).

Home Office officials are supposed to take the claim at its highest, in the sense that they should give the person the benefit of the doubt. If the account given by the person of what happened to them in the past seems outlandish or unlikely, that will not normally mean the claim is clearly unfounded; “[o]nly where the interviewing officer is satisfied that nobody could believe the applicant’s story will it be appropriate to certify the claim as clearly unfounded on the ground of lack of credibility alone” (para 60).

It therefore does not take much for a person seeking asylum to show that their claim is not clearly unfounded.

When might the clearly unfounded presumption be rebutted?

Just because the person comes from a country that is generally safe for most people does not mean it will be safe for them. The presumption is a rebuttable one, meaning that the person concerned can argue that the country is not safe for them personally even if it is generally safe for others.

In ZL and VL, the Court of Appeal said that the process for consideration in individual cases should be that the caseworker will:

i) consider the factual substance and detail of the claim

ii) consider how it stands with the known background data

iii) consider whether in the round it is capable of belief

iv) if not, consider whether some part of it is capable of belief

v) consider whether, if eventually believed in whole or in part, it is capable of coming within the Convention.

Essentially, the asylum claim has to be properly considered. Only then, if on any legitimate view it cannot succeed, can the claim be said to be clearly unfounded.

What happens to a clearly unfounded asylum claim?

If after the asylum claim is considered it is found be clearly unfounded, the person concerned is not permitted to appeal to the immigration tribunal. In previous years, a person could appeal but only after they were removed. However, this very limited safeguard was removed by section 28 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 with effect from 28 June 2022.

As an aside, I cannot begin to tell you how hard I would laugh if the government were to lose a legal challenge because of the scrapping of that right of appeal.

So, once an asylum claim is made, it is supposed to be properly and carefully considered by the Home Office. If the asylum claim is rejected, it may also be certified as clearly unfounded, in which case the person concerned has no right of appeal and that is the end of the normal asylum process for them. They may then be removed from the country, absent any other legal challenge.

Can a decision that an asylum claim is clearly unfounded be challenged?

Even if the person has no right of appeal to the immigration tribunal against the refusal or the clearly unfounded certification decision, there is another possibility of a legal challenge. The decision to certify the asylum claim as clearly unfounded can be challenged by way of an application for judicial review.

This is right and proper. Without this safeguard in place, officials at the Home Office could potentially apply a very lax approach and not look at claims conscientiously. The chance that a genuine refugee might be returned to a country and persecuted would increase. In the current climate it seems far from inconceivable that caseworkers might be subject to political pressure, for example, or very poorly trained caseworkers might be deployed to the task.

An application for judicial review is very different to an appeal. An appeal is all about the merits of the underlying case. In this context, the question on an appeal is whether a person is really a refugee or not. The judge can and indeed must make their own decision about that after hearing both sides of the argument. In an application for judicial review, the judge is considering whether the Home Office decision was lawful or not. There are only very limited grounds on which a judge might decide that a decision was unlawful. The grounds for challenge include matters such as whether something important was overlooked, whether something irrelevant was taken into account, or whether the decision was so unreasonable that no reasonable decision maker could have reached the same decision.

Non lawyers might well think this is a distinction without a difference. The reality is that it is hard to succeed in an application for judicial review. And there is also a screening process where a judge’s permission is needed to bring a case. In contrast, any person who is refused asylum is entitled to bring an appeal and over half of asylum appeals succeed.

Can clearly unfounded cases be fast tracked?

The short answer is yes.

Firstly, it is not necessarily incompatible with the Refugee Convention. The UN agency responsible for refugees, UNHCR, has long maintained that an accelerated process for clearly unfounded claims is not incompatible with the Refugee Convention as long as certain procedural safeguards are observed.

Secondly, there used to be a fast track for clearly unfounded cases in the United Kingdom but it was eventually scrapped by the new Conservative government in November 2010. The process was based at the Oakington detention centre near Cambridge, a barracks that was converted for the purpose in 2000. Then immigration minister Damien Green said that “It was a temporary solution and we never intended to use this facility long term”. Closure had been planned since at least 2006 but the final date was only set in August 2010, and no replacement facility was considered necessary.

The “Oakington process” as it was known involved detaining asylum seekers on arrival and sending them to the centre. There they would be allocated a government-funded lawyer, interviewed by the Home Office and would receive an initial asylum decision, all within seven to ten days. They would then be released into asylum accommodation if they were allowed to pursue an appeal or, potentially, would be transferred to a more secure detention centre if they faced removal.

This process was subject to a legal challenge, but the government won. The claimants argued that detaining a person purely for administrative convenience irrespective of whether there was a risk of them absconding was unlawful in domestic and human rights law. They lost in the case of Saadi v United Kingdom (App no 13229/03), decided by the European Court of Human Rights in 2008. But they lost because the court decided that adequate safeguards were in place (see below).

What does it take for a fast track asylum process to be lawful?

The right to liberty is enshrined in Article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. It states that “No one shall be deprived of his liberty…”. But it goes on, “…save in the following cases and in accordance with a procedure prescribed by law…”. And then goes on to list several permitted purposes, including “…the lawful arrest or detention of a person to prevent his effecting an unauthorised entry into the country or of a person against whom action is being taken with a view to deportation or extradition”.

The court in Saadi went on to consider whether the detention of asylum seekers at Oakington was nevertheless unlawful on the basis that it was arbitrary. To avoid being arbitrary, the detention

must be carried out in good faith; it must be closely connected to the purpose of preventing unauthorised entry of the person to the country; the place and conditions of detention should be appropriate, bearing in mind that “the measure is applicable not to those who have committed criminal offences but to aliens who, often fearing for their lives, have fled from their own country” (see Amuur, § 43); and the length of the detention should not exceed that reasonably required for the purpose pursued.

Assessed against these criteria, the court concluded that the Oakington fast track was not arbitrary. The purpose of detention was to achieve speedy resolution of around 13,000 asylum claims per year at a time when around 84,000 asylum claims were being made per year. Fast resolution benefited asylum claimants in general because, as Lord Flynn had put it in the House of Lords previously, “getting a speedy decision is in the interests not only of the applicants but of those increasingly in the queue”.

As regards the conditions of detention, the court concluded that Oakington “was specifically adapted to hold asylum seekers and that various facilities, for recreation, religious observance, medical care and, importantly, legal assistance, were provided.” Detention was for seven days only, a period which “cannot be said to have exceeded that reasonably required for the purpose pursued.”

On this basis, the Oakington process was found to be lawful.

What is the government now proposing?

The white list of countries designated as presumed safe is not new and has been operating since 1996. Albania has been on that list since 2004. What looks to be new about the slightly vague proposals being floated by the Home Office is that claims from white list countries would be subject to a fast track system.

This would potentially resurrect a system that was operational between 2000 and 2010 and which was held to be lawful by the European Court of Human Rights in its previous incarnation. As we have seen, though, there need to be safeguards, including detaining for only a short time and providing legal advice.

The government certainly has to do something about the ballooning asylum backlog. That is very likely to involve some sort of fast tracking of some applications. Personally, I’d like to see fast tracking of applications that are very likely to succeed. 98% of claims from Afghanistan, Eritrea and Syria succeeded in the year ended September 2022. 87% of Sudanese claims succeeded. 82% of Iranian claims succeeded – and that was before the recent protests and crack down in that country. There is no reason whatsoever to keep these refugees waiting for years on end in temporary and sometimes squalid accommodation on destitution level asylum support.

SHARE