- BY Naga Kandiah

Are Home Office consent orders worth it?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

A recent case shows that practitioners should beware the Home Office’s use of consent orders in judicial review claims, write Kim Renfrew and Naga Kandiah of MTC & Co. Solicitors.

Our client SP is an asylum seeker of Sri Lankan origin. SP submitted further evidence to the Home Office, to support his claim to have a well-founded fear of persecution. This was rejected as being insufficient to equate to a fresh asylum claim.

SP proceeded to challenge this refusal by way of judicial review. Permission to apply for judicial review of the decision was granted on all grounds by the Upper Tribunal.

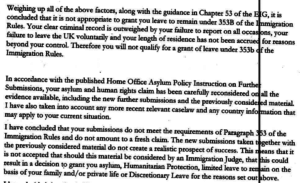

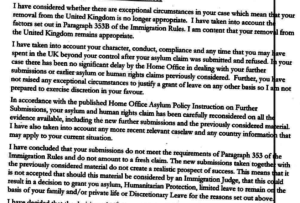

The Home Office responded to this grant of permission, by offering to consent to reconsider the decision by way of consent order. But the reconsidered decision was in substance identical to that initially challenged.

Here, for instance, are the concluding paragraphs of each one:

It is a well-established principle that permission to apply for judicial review will not be granted unless the substance of the decision would be affected by compliance with correct procedure.

Clearly, the original decision was deemed to be defective by the court. In her reconsideration, the Secretary of State has issued a decision which is in substance the same, albeit with a slightly more detailed analysis of the claim. Yet the refusal retains the same rejection of a prospect of success under paragraph 353.

This means that the Secretary of State’s offer to reconsider has had no material effect and runs contrary to the reasoning of the judge in granting permission to apply for judicial review. In order to proceed with his appeal against the Home Office’s decision, SP has no choice but to make a further application for permission to apply for judicial review.

The approach of the Home Office runs contrary to the principles of justice and fairness. The Home Office hands out consent orders in an attempt to force applicants to withdraw their claims. It would appear that a decision by the Upper Tribunal that the Home Office’s decision making was Wednesbury unreasonable has greater weight in influencing a more favourable fresh decision than the Home Office agreeing to reconsideration by consent.

In light of the experience in the case of SP, and other cases covered on this blog, reconsideration does little more than buy additional time and the outcome may be a decision which is not materially different.

The impetus for the Home Office to issue such consent orders may find its origins in the backlog of immigration judicial review cases. The reconsideration of such decisions via consent order appears more like an attempt to slow the build-up of judicial review cases, rather than to deliver a just outcome to applicants. Ultimately, this undermines the rationale for judicial review as providing a system of protection for those adversely affected by poor decision making of public bodies.

The Home Office will often agree to pay the claimant’s legal costs, which translates as a drain on public expenditure. If new decisions do not address the issues challenged by way of applications for judicial review, this is a waste of taxpayers’ money. Further, it is a waste of time for genuine applicants and their representatives, who are left in limbo regarding their claims.

One Response

Unless I am missing something, I am not sure that this blog makes sense. It seems to be premised on the basis that if a JR is dealt with by way of a Consent Order, then the reconsidered decision should always be favourable to the client. This cannot be correct. The reconsidered decision should be lawful (& often they are not), but a Consent Order and agreement to reconsider case does not mean the client is now going to win. Also, the phrase “Clearly, the original decision was deemed to be defective by the court.” is not correct – when permission is granted, the original decision is deemed to be ARGUABLY unlawful. And I am not sure about this either: “The Home Office hands out consent orders in an attempt to force applicants to withdraw their claims.” On a successful JR the most you can achieve is the quashing of the original decision such that the SSHD will have to go away and reconsider the matter on a lawful basis – so surely a Consent Order is almost invariably in the client’s best interests as the client achieves the required outcome much sooner and without any risk. Even if the SSHD loses a full JR hearing and then has to make a new decision, this does not mean client will necessarily be successful. Perhaps I am missing something about this blog, but I am just unsure if I either get it or agree with it.

Although I do agree that the SSHD often makes really poor decisions & then repeats this again & again (I have many cases where there have been repeat successful JRs because the SSHD cannot seem to make a lawful decision) – just not sure if Consent Orders are the problems – SSHD decision-making seems to be the problem.