- BY Colin Yeo

Free Movement review of the year 2020

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleIt hasn’t exactly been one of the all time greats, has it? Nevertheless, every year I attempt to stand back from the constant updates and news, reflect on what really happened in immigration law during the year and try to look ahead to the coming rotation around our sun. If you are minded to take a trip down Memory Lane, you can read my previous reviews for 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014 and 2013.

Last year I wrote that the EU Settlement Scheme had been the defining event of 2019, as the emergence of the Windrush scandal had been of 2018. Both continue to play themselves out. The EU Settlement Scheme continues apace, with well over 4 million applications having been made and decided. What is not known, and never will be, is how many people do not apply and therefore lose lawful status for themselves and their children. Windrush has led to only very superficial immediate, short term changes but I continue to hope that the greater awareness it has engendered of the hostile environment, our immigration history and our immigration laws generally might lead to major reform over time. Understanding how awful our system has become is a precondition to meaningful reform, although it certainly does not make reform inevitable.

Coronavirus

The defining event of 2020 was without doubt the coronavirus pandemic. This was completely unexpected and unpredicted. In immigration policy, one of the stand out effects has been the dramatic fall in immigration and an exodus of EU citizens. Net migration has gone negative: more people left the United Kingdom than arrived. All along we have warned that only a major economic crisis would meet the old net migration target, and so it has proven. Whether this has any impact on longer term policy will be interesting to see: if lower levels of immigration continue and the pool of available migrant workers remains small, will this influence public opinion? The links between actual immigration and public opinion are complex: the issue of immigration certainly rose up the agenda in the years when net migration rose and remained high but then fell after Brexit even though net migration remained high. And as we have seen with the small boats of refugees over the summer, even relatively tiny numbers of migrants can have a massively disproportionate impact on public opinion.

In immigration law, the government has responded to the pandemic with a series of shoddy, ill-thought-through, extra-legal, short-term measures. Officials have implemented the absolute bare minimum that the government could get away with, presumably having presented broad options to the politicians responsible.

There are likely to be adverse consequences for individual migrants in the coming years flowing from what I assume is a deliberate political decision not properly to address the effects of the pandemic. It is unclear that the so-called ‘extensions’ of leave were legally valid and effective, for example, and the Home Office will undoubtedly use that against Bad Migrants in the future. As with the not-so-genius idea of introducing a Comprehensive Sickness Insurance requirement in 2011 and the roll-out of the hostile environment in general, the consequences of such policies for countless others would probably be considered irrelevant, if considered at all. The Home Office and migrants will end up being fixed with these consequences by court decisions for years to come.

Brexit

Brexit did finally happen in 2020. The United Kingdom formally ceased being a member of the European Union on 31 January 2020, and on that date British citizens lost their status as Citizens of the Union. The transition period lasting until 31 December meant that most people will not really have noticed so far, though. That may well start to change in 2021 as the effect of the end of free movement both for British citizens travelling to the EU and EU citizens travelling to the UK start to take effect.

Last year’s annual review took the immigration policies announced at the 2019 election at face value: a schoolboy error, in hindsight. Since then, the government has abandoned plans for sector-based low skilled immigration routes, other than a relatively small one in agriculture. It is hard to see how the British economy can recalibrate itself to rely on domestic rather than migrant labour very rapidly without pain and shortages, particularly since the exodus of EU citizens appears to have diminished the pool of workers the UK government hoped would gain settled status and fill labour needs in the short term. If mass unemployment and heavily reduced tourism into the United Kingdom follows the tailing off of the pandemic domestically then perhaps there will be less demand for workers and more supply, but otherwise we may yet see some short term migration routes introduced.

The end of UK participation in the EU’s Dublin system of allocation of responsibility for deciding asylum claims will actually reduce the number of asylum seekers coming into the UK given that more refugees have entered the UK under Dublin rules than have been removed in recent years. However, in the absence of any replacement to Dublin, the impossibility of removing refugees who arrive by small boat to France or elsewhere is going to be politically problematic for the government. We can expect politicians to look for other ways to perform in public their hostility to small boat arrivals.

Refugees

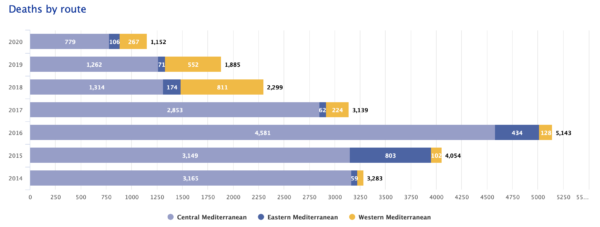

This year over 1,150 refugees drowned in the Mediterranean and a further 14 died in northern France, presumably attempting to reach the United Kingdom. These deaths are the price that our societies here in Europe are willing for others — and to a lesser extent ourselves, given the moral cost — to pay to keep people out.

It has been an abysmal year for refugee law and policy in the United Kingdom. The rise in small boat crossings this year represented a change in means of entry to the United Kingdom; the actual number of asylum claims being made fell. Nevertheless, all sorts of Heath Robinson madcap ideas were floated (sorry…) to prevent refugees reaching our shores, from wave machines to buoyant barricades to nets. We have reached the miserable point where inhumanity is the whole purpose of asylum policy, rendering any objection on this basis pointless in terms of persuasion or prevention. The fact that refugees would inevitably either die at sea as a consequence or would enter British custody anyway seemed to me better arguments against if the object was to prevent the policies being implemented.

The new immigration rules on refugees entering the United Kingdom via a safe third country come into effect tomorrow, the very same day that the United Kingdom loses the capacity to remove refugees who entered via a safe third country. These rules seem to me genuinely disastrous, not so much because they will lead to actual removals to safe third countries — although I may prove to be wrong about that — but because almost every single asylum claim made in the UK can be placed on hold for a ‘reasonable’ period. Massive delays are already a problem in asylum cases and this is going to make the situation much, much worse. This sets up a vicious circle: even harsher measures are then called for to deal with the problems created by previous counter-productive cruelty.

These sorts of policies are not based on logic or reason and as long as small boat refugees remain in the public eye, ever-harsher performance of cruelty against them will be called for. I fear for our continued ratification of the Refugee Convention itself. At some point, with undecided asylum claims mounting and media pressure continuing, the politicians will start to run out of eye-catching new policies they can announce. Withdrawing from the Convention would sound like a good idea to those who dislike irregular arrivals but would in reality achieve nothing given that (a) removals to safe third countries are not clearly barred by the terms of the Convention anyway and (b) I assume, perhaps naively, that we are not prepared to send refugees back to their countries of origin to die. Whether it actually works is not what matters, though: it is whether a certain segment of public opinion think it might work.

Migration as threat

If there is a theme to all of these developments, it is that migrants are constantly perceived and treated by politicians and civil servants at the Home Office as a threat. The best piece I’ve ever read on the Home Office mentality was Home Office Rules by William Davies back in 2016 in the LRB. Essentially, the Home Office as an institution sees everything as a narrow, short-term security issue and its job as protecting the immediate safety of existing citizens. This mindset may explain a lot of otherwise rationally hard to understand Home Office policy. Civil servants do not want migrants to have secure status, still less citizenship, because it makes them harder to remove if they become undesirable. This is to an extent understandable, if your world is entirely dominated by the perceived need to deport foreign criminals and thereby protect both the public and politicians. But it ignores the wider social, economic and cultural effects and may well cause far more harm to the public over time than it prevents.

If Roma, low skilled, non-English-speaking, homeless and other ‘undesirable’ or ‘low-value’ EU citizens become unlawfully resident and therefore readily removable after the end of the EU Settlement Scheme, that is fine. If young, black men never acquire citizenship, that is convenient, as it means those convicted of offences can readily be deported. If self-sufficient and student EU citizens are excluded from citizenship, that is acceptable. It is not that officials or politicians want to remove all members of these groups, rather that it is convenient later to be able to remove some of them. This is the price that almost all migrants and often their children too have to pay, so that a handful can be targeted for removal later. This approach contrast markedly with the fast track to citizenship available for wealthy investor migrants.

Existing and perhaps former civil servants may not recognise this as a conscious thought process or policy objective. The fact that this insecurity of status is a predictable outcome of multiple Home Office laws and policies over a prolonged period should cause them to have a long, hard think about what they are really trying to achieve. That positive value is attached to wealthy investor migrants also tells us that no positive value is attached to others.

It is this mindset that needs to change. In my book, Welcome to Britain, I advocate seeing migrants as future citizens. Once admitted on work, family and refugee routes, the fact is that the vast majority are going to stay, whether legally or not. It would be better to help them settle, integrate and live their best lives rather than pointlessly punishing them with our current set of immigration laws and policies.

Here on Free Movement

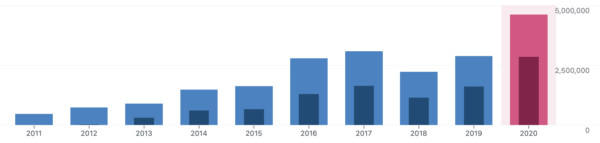

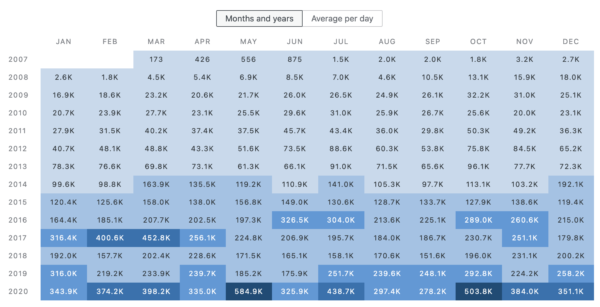

Finally, this is the bit where I go full Trump. We had an unexpectedly huge year on Free Movement, receiving nearly five million page views from nearly three million visitors this year alone. We topped half a million page views in each of the months of May and October. Total page views since the beginning of the blog in March 2007 stand at 21.5m and our average is well over 10k per day now. I continue to be astonished by how many people visit this website. The increase over last year is not due to increased output: we put out 479 blog posts consisting of 470,655 words, which is basically the same as 2019.

The email list stands at 23k subscribers, up around 3k on last year. We now have over 3k active paying members, up from around 2,800 this time last year. My own Twitter account @colinyeo1 has 26k followers and @freemovementlaw now has 8k, the latter a considerable annual increase.

Looking ahead, we are planning some changes to the website early in the year. It is now four years since our last redesign, which is considered an Age on the interwebs. Rather than substantially changing the look and feel of the site, though, we’re mainly looking at ways to streamline and simplify things behind the scenes. I am also, paradoxically, wondering about adding a jobs board so that advertising jobs with us is easier and cheaper than at present. If you have any significant requests for changes to the way the website works then drop us a line.

I will also be considering whether to increase membership fees during the year, once the pandemic is behind us. Individual membership fees have not gone up since they were first set at £200 per year in 2014. Membership has grown considerably since then, but so too have costs.

On a personal note, I am hugely grateful to CJ, Faye and the regular Free Movement contributors for their hard work. The swift turn arounds when a new Statement of Changes drops or similar are particularly impressive, and Nath deserves special mention. I am also very thankful to all the readers and members who make Free Movement possible. All of this support has enabled me to spend time researching and writing Welcome to Britain, which I hope stands as a record of what our immigration system had become by 2020. In the year ahead I will be working on a new OISC Level 2 online training course, looking at introducing an element of tutoring or guided learning to some courses and working on a new textbook on refugee law for Bristol University Press. On the barristering front, I will continue to take on legal aid asylum appeals and pro bono work for Bail for Immigration Detainees.

SHARE