- BY Ben Amunwa

EU children can be lawfully resident in the UK without exercising treaty rights

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The Upper Tribunal judgment in MS (British citizenship; EEA appeals) Belgium [2019] UKUT 356 (IAC) confirms that certain EU citizen children in the UK can be considered lawfully resident for the purposes of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, even if they (or their EU citizen parents or carers) have not exercised treaty rights and have no official Home Office documentation.

Background

MS appealed against the Secretary of State’s decision to refuse to revoke a deportation order made against him under the EEA Regulations 2016. He was successful at the First-tier Tribunal. The Secretary of State appealed to the Upper Tribunal where four separate hearings followed in which I represented MS, instructed by Duncan Lewis.

The Upper Tribunal allowed the Secretary of State’s error of law appeal in MS (appealable decisions; PTA requirements; anonymity) [2019] UKUT 216 (see my previous write-up here). It decided that MS had no in-country right of appeal against the refusal to revoke the deportation order against him on EU law grounds. Any such appeal had to be pursued from abroad.

However, because the Secretary of State’s decision letter dealt with Article 8 as well, the First-tier Tribunal had erred by failing to address MS’s human rights claim. The decision of the First-tier Tribunal was set aside with directions for it to be re-made by the Upper Tribunal.

This latest judgment concerned the remaking of MS’s human rights appeal on Article 8 grounds only. Unusually, despite MS being an EU citizen, he could not now rely on EU law grounds of appeal to resist his deportation — and the application of domestic deportation law to EU citizens is somewhat problematic.

The law

Part 5A of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 is Parliament’s attempt to codify the factors that judges should consider when deciding immigration appeals based on Article 8. It was not drafted with EU nationals specifically in mind.

Section 117B applies to all Article 8 cases and states that:

(4) Little weight should be given to—

(a) a private life, or

(b) a relationship formed with a qualifying partner,

that is established by a person at a time when the person is in the United Kingdom unlawfully.

In Akinyemi v SSHD [2017] EWCA Civ 236 (at paragraphs 41 to 42), the Court of Appeal gave a restrictive interpretation of the term “unlawfully” in section 117B. It concluded that where a person had a legitimate expectation that they belonged in the UK, it would be wrong to characterise their stay as unlawful.

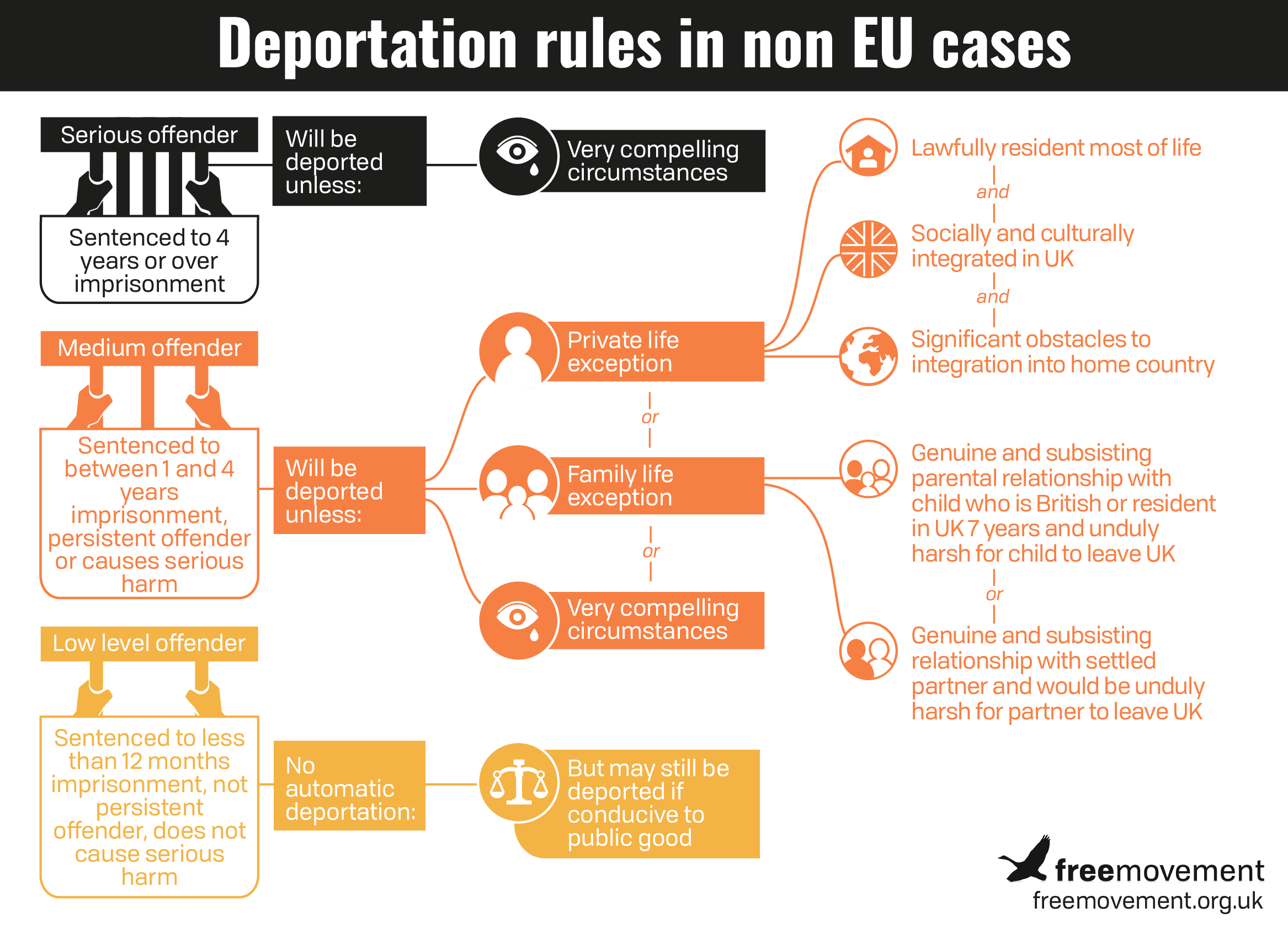

Section 117C applies to criminal deportation cases. One of the two exceptions to deportation, in section 117C(4), among other things requires that the deportee “has been lawfully resident in the United Kingdom for most of C’s life”.

In Secretary of State for the Home Department v SC (Jamaica) [2017] EWCA Civ 2112, the Court of Appeal found it “somewhat surprising” that the words “lawful residence” were not defined in the deportation provisions of the Immigration Rules which mirror section 117C.

Although the 2002 Act prompts judges to consider the lawfulness of a person’s presence and residence in the UK, it does not explain how these provisions apply to EU nationals, who are exempt from immigration control due to free movement rights.

The Upper Tribunal noted the practical difficulties this raises (at paragraph 124):

The problem is that, whilst it is relatively straightforward to ascertain whether a person, who is not an EEA national and therefore requires 1971 Act leave at all relevant times, has had or did not have such leave at any point in time, it may often be difficult to look back at the immigration history of an EEA national and ascertain at what points in time he or she was entitled to be in the United Kingdom by virtue of an enforceable right of the kind described in section 7(1) of the [Immigration Act] 1988…

On behalf of MS, we argued that “lawful residence” for the purposes of section 117C(4) should not be tied to the exercise of treaty rights. The Secretary of State’s position was that it should be (as spelled out in her unrelated policy on long residence applications, page 25).

The Upper Tribunal’s decision

The tribunal agreed with the Secretary of State’s position that an adult EU national who is not exercising treaty rights and who has no other lawful basis for being in the UK is not lawfully resident here (see paragraphs 133 to 135 and 138).

But compliance with Article 8 requires tribunals to make appropriate allowances, particularly where an EU citizen was a minor during their time in the UK. A flexible approach should be adopted where the facts suggest that an EU child’s time in the UK should not be categorised as unlawful.

At paragraph 139, the Upper Tribunal held:

…an EU national who came as a child to the United Kingdom may have profound difficulties in showing that his or her residence during their minority was in accordance with EU law, compared with an adult who makes the conscious decision to come here in order to exercise the right of free movement of a worker. A child will be unable directly to regularise their status, even if it were to become apparent that it might be necessary to do so. In such a case, for the purposes of looking at Article 8 through the lens of Part 5A, the Tribunal needs to appreciate this difficulty.

In this case, the factors which led the Upper Tribunal to conclude his residence was lawful included that “he was under the control of his adoptive father and his mother; that he was able to attend school and college without any questions being asked about his status; and that no action was taken or even contemplated by the respondent in respect of him or his mother”.

The British citizenship point

A further issue was the relevance in Article 8 appeals of a previous but unexercised entitlement to register as, or apply to be registered as, a British citizen while a minor.

During some of his childhood, MS would have met the requirements for discretionary registration as a British citizen under section 3(1) of the British Nationality Act 1981. But no application was made and difficulties in the appellant’s upbringing resulted in him going into care.

The Upper Tribunal concluded that a previous entitlement to apply for registration was not relevant, notwithstanding the approach of the Court of Appeal in Akinyemi v SSHD [2017] EWCA Civ 236. It held:

The key factor is not whether someone had a good chance of becoming a British citizen, on application, at some previous time or times. Rather, it is the nature and extent of the individual’s life in the United Kingdom. Thus, in the present case, the factors weighing in the appellant’s favour will include the length of time he has been in the United Kingdom, whether any part of that time involved what might be described as “formative years”; and the nature and extent of his private and family life in this country.

Despite MS spending most of his life and childhood in the UK, the Upper Tribunal dismissed his human rights appeal. His repeat offending and re-entry into the UK in breach of his deportation order meant that the public interest in deportation outweighed his private life claim.

Conclusion

This is a significant step forward for the protection of EU nationals who have spent their childhood in the UK but have no official Home Office documentation. Under current government plans, such persons will be treated as unlawful migrants from January 2021 in the event of a “no deal” Brexit.

There are parallels between MS and the types of cases that may become more common in a post-Brexit environment. EU children in care and EU care leavers (such as the appellant) are particularly vulnerable to the risk of becoming undocumented migrants. That vulnerability is expected to have more serious consequences if and when free movement is abolished from January 2021.

For now, MS clarifies that respecting the Article 8 right to private life for EU citizens who have grown up in the UK may require the statutory human rights framework in Part 5A of the 2002 Act to be applied flexibly, taking into account the particular barriers they may have faced in obtaining Home Office documentation through no fault of their own.

(1) If, on appeal, an issue arises as to whether the removal of a person (P) from the United Kingdom would be unlawful because P is a British citizen, the tribunal deciding the appeal must make a finding on P’s citizenship; just as the tribunal must do so where the consideration of the public interest question in Part 5A of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 involves finding whether another person falls within the definition of a “qualifying child” or “qualifying partner” by reason of being a British citizen.

(2) The fact that P might, in the past, have had a good case to be registered as a British citizen has no material bearing on the striking of the proportionality balance under Article 8(2) of the ECHR. The key factor is not whether P had a good chance of becoming a British citizen, on application, at some previous time but is, rather, the nature and extent of P’s life in the United Kingdom.

(3) If P is prevented by regulation 37 of the Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2016 from initiating an appeal under those Regulations whilst P is in the United Kingdom, it would defeat the legislative purpose in enacting regulation 37 if P were able, through the medium of a human rights appeal brought within the United Kingdom, to advance the very challenge to the decision taken under the Regulations, which Parliament has ordained can be initiated only from abroad.

(4) In considering the public interest question in Part 5A of the 2002 Act, if P is an EEA national (or family member of an EEA national) who has no basis under the 2016 Regulations or EU law for being in the United Kingdom, P requires leave to enter or remain under the Immigration Act 1971. If P does not have such leave, P will be in the United Kingdom unlawfully for the purpose of section 117B(4) of the 2002 Act during the period in question and, likewise, will not be lawfully resident during that period for the purpose of section 117C(4)(a).

(5) The modest degree of flexibility contained in section 117A(2) of the 2002 Act, recognised by the Supreme Court in Rhuppiah v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] UKSC 58, means that, depending on the facts, P may nevertheless fall to be treated as lawfully in the United Kingdom for the purpose of those provisions, during the time that P was an EU child in the United Kingdom; as in the present case, where P was under the control of his parents; was able to attend school and college without questions being asked as to P’s status; and where no action was taken or even contemplated by the respondent in respect of P or his EU mother.