- BY colinyeo

Do dual EU-UK citizens have rights under EU law?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe question of what rights are enjoyed by an EU citizen who naturalises as a British citizen and becomes a dual citizen has become a critically important one in the context of Brexit. There is huge uncertainty amongst EU citizens and their family members living in the UK about their future status and there is huge interest in the possibility of naturalising as British citizens.

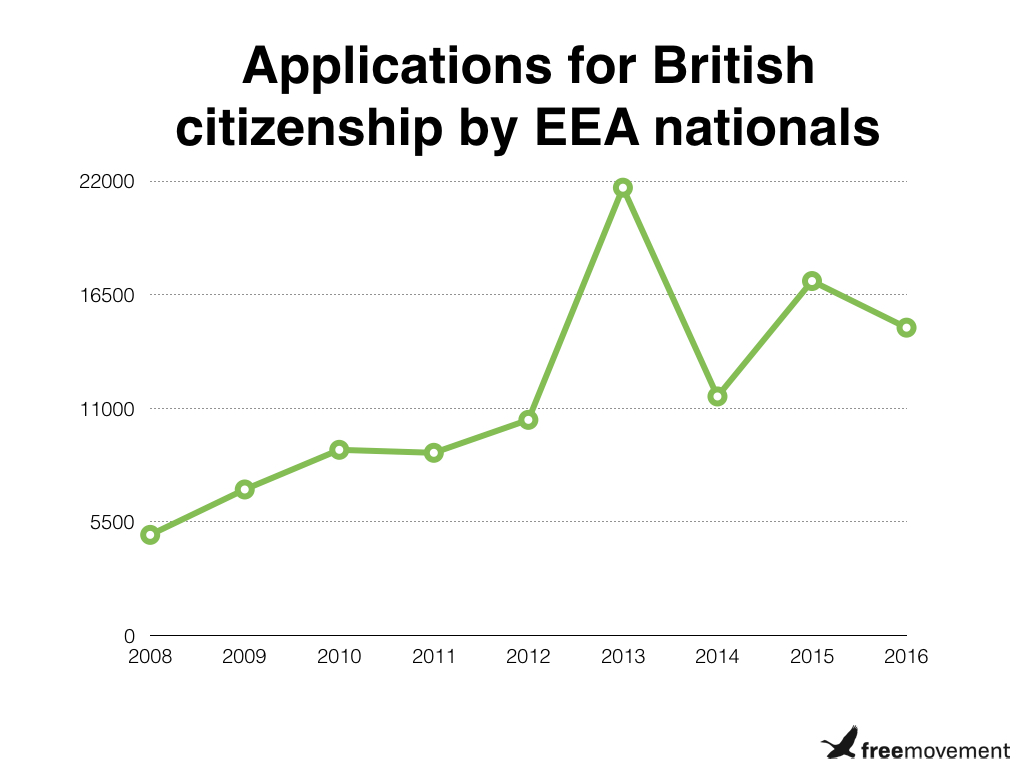

At the same time, though, it has to be said, the number of EU citizens successfully applying for naturalisation as British actually fell between 2015 and 2016, from 17,158 to 14,901. This was presumably because of additional hurdles the UK Government has erected in the way of EU citizens seeking British citizenship.

The question of whether to become formally and legally British is a very personal question and many EU citizens have mixed feelings; on the one hand they feel they wish to secure their position beyond doubt but on the other they feel betrayed by their treatment at the hands of the British Government. Nationality is a complex question of identity, not just a legal status.

Impact of loss of rights for dual citizens

There is a problem with becoming a dual national British citizen, though. The UK changed its approach to dual citizens in 2012 and now denies any dual citizen any rights under EU law.

For some this will not matter once they become British. For any EU citizen who has family members from outside the EU living with them or who might want family members to live with them in future (for example when parents develop care needs) this is a huge problem, though. The moment such a person becomes a British citizen, any family member living with them from outside the EU who was previously resident under EU law will become unlawfully resident.

Clara is a Spanish national living in the UK with her Colombian husband. Clara has lived and worked in the UK for over 10 years working for the NHS. She married her husband in 2014 and they have a child, who was born a British citizen because Clara held permanent residence by the time of his birth. Clara is worried about her job and position in the UK following the referendum and so she applies for and obtains a permanent residence certificate. She then applies for naturalisation.

The moment Clara becomes a British citizen, her husband will be living illegally in the UK, at least according to the Home Office. He will lose his right under EU law to live as the family member of an EU citizen. Any work he does is unlawful and his employer risks a civil penalty of £20,000 if continue to employ him. He has no right to rent accommodation and his landlord risks a fine unless he is removed from the tenancy agreement. He cannot open a bank account and from the autumn of 2017 any existing bank account will automatically be closed down. To regain legal status he would have to apply for leave to remain under the UK immigration rules. To do so he would probably need to apply from abroad and would need to meet the English language requirements and the Minimum Income Threshold of £18,600.

These consequences are obviously dire. Why the Home Office wishes to penalise in this way EU nationals who become British citizens and their families is mysterious.

Looking forward, the dual citizen will also lose any right to bring family members to the UK under EU law in future, if EU law continues to exist following Brexit. This will apply to EU and non EU family members. This may not seem a problem now but it may well become a significant issue in future.

Danielle is a French citizen. She is married to a British citizen and has permanent residence and because of Brexit she decides to naturalise as a British citizen. She has no family members from outside the UK who currently live with her.

Following Brexit, let us imagine that EU citizens already resident in the UK retain their existing EU law rights. Non resident EU citizens are subject to a new immigration regime of some sort, though, which allows them visa free access to visit the UK but does not allow them a proper right to reside unless they meet conditions such as working in a role that could not be filled by a British citizen following an attempt at recruitment.

Danielle’s widowed mother develops care needs and Danielle wishes to bring her to the UK to look after her. Danielle’s mother has no right to reside in the UK, only to visit. Danielle would have been able to bring her mother to the UK under EU law as long as her mother was dependent, which she is. However, according the Home Office Danielle lost her EU rights when she became British and must instead rely on the UK Immigration Rules. These make it virtually impossible to bring parents to the UK. Danielle will either need to leave the UK to care for her mother or will need to abandon her.

Why has the UK done this?

So, why has the UK changed its approach? It happened after a Court of Justice of the European Union case called McCarthy C-434/09. In that case a British woman applied for and obtained an Irish passport on the basis of her Irish ancestry. Without ever leaving the UK to exercise Treaty rights in another Member State, she then tried to argue that as a dual citizen her Jamaican spouse should be allowed to live in the UK under EU law. The Court rejected this argument and held that neither Directive 2004/38 nor Article 21 TFEU apply to:

a Union citizen who has never exercised his right of free movement, who has always resided in a Member State of which he is a national and who is also a national of another Member State

Until then, the UK had followed a relaxed approach to dual citizenship and where an EU citizen became British the EU citizen would retain his or her EU rights. Following the McCarthy judgment, the UK changed its approach and now takes the view that EU rights are instantly lost the moment a person becomes British.

The Immigration (European Economic Area) Regulations 2016 impart rights to EEA nationals, but EEA national is defined as follows at regulation 2 on interpretation of terms:

“EEA national” means a national of an EEA State who is not also a British citizen

The effect is to remove EEA nationals and their family members from the scope of the UK’s implementation of EU law immediately on the EEA national becoming a British citizen.

Very limited transitional arrangements are set out in Schedule 6 of the Immigration (EEA) Regulations 2016 but these only protected a narrow group of EEA nationals and family members already resident in 2012 who had permanent residence or had applied for residence documents.

Upcoming legal challenge

Many lawyers believe the new UK approach is wrong. And shortly the Court of Justice will be ruling again on the issue, in the case of Lounes C-165/16. In this case a Spanish national came to the UK, exercised her Treaty rights, acquired permanent residence and eventually naturalised as British. She married an Algerian citizen, who applied for a residence card under EU law on the basis of being a family member of an EU citizen. The application was refused by the Home Office.

When the case reached court, the court referred the following question to the Court of Justice:

Where a Spanish national and Union citizen:

i. moves to the United Kingdom, in the exercise of her right to free movement under Directive 2004/38/EC (1); and

ii. resides in the United Kingdom in the exercise of her right under Article 7 or Article 16 of Directive 2004/38/EC; and

iii. subsequently acquires British citizenship, which she holds in addition to her Spanish nationality, as a dual national; and

iv. several years after acquiring British citizenship, marries a third country national with whom she resides in the United Kingdom;

are she and her spouse both beneficiaries of Directive 2004/38/EC, within the meaning of Article 3(1), whilst she is residing in the United Kingdom, and holding both Spanish nationality and British citizenship?

The reference was made in March 2016 and the hearing is apparently due to take place in May 2017, according to Counsel instructed in the cases Mr Parminder Saini:

1/2: R, Lounes v SSHD: Lead JR re #EU #freemovement rights of Union Citizens with dual UK nationality to be heard by the Grand Chamber of…

— Parm Saini (@PPSSaini) March 21, 2017

2/2: …Grand Chamber of the CJEU in May 2017. I shall appear for the Applicant, with the Kingdom of Spain intervening #ECJ #CJEU #Brexit

— Parm Saini (@PPSSaini) March 21, 2017

The Spanish Government is intervening, presumably to seek to protect the EU law rights of its citizen. Watch this space. Any further details will appear on the case page for the Court of Justice. The hearing will take place, then there will be a formal Opinion by the allocated Advocate-General and then the Court will give judgment. The Court usually reaches the same conclusion as the Advocate-General but not always.

A lot turns on the outcome of this case.