- BY Colin Yeo

Does the Human Rights Act prevent us deporting serious criminals?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleIt is very widely believed that the Human Rights Act stops the UK from deporting foreign criminals whence they came. To a limited extent, there is some truth in this. Some appeals against deportation decisions do succeed on human rights grounds. Not many, though, and none succeed because of the Human Rights Act as distinct from the European Convention on Human Rights. Other appeals against deportation succeed under EU law or the Refugee Convention.

It is also strange but true that, contrary to popular belief, the era of the Human Rights Act has actually seen a massive downgrading of protection against deportation for foreign criminals. Read on to find out more.

Other legal grounds for resisting deportation

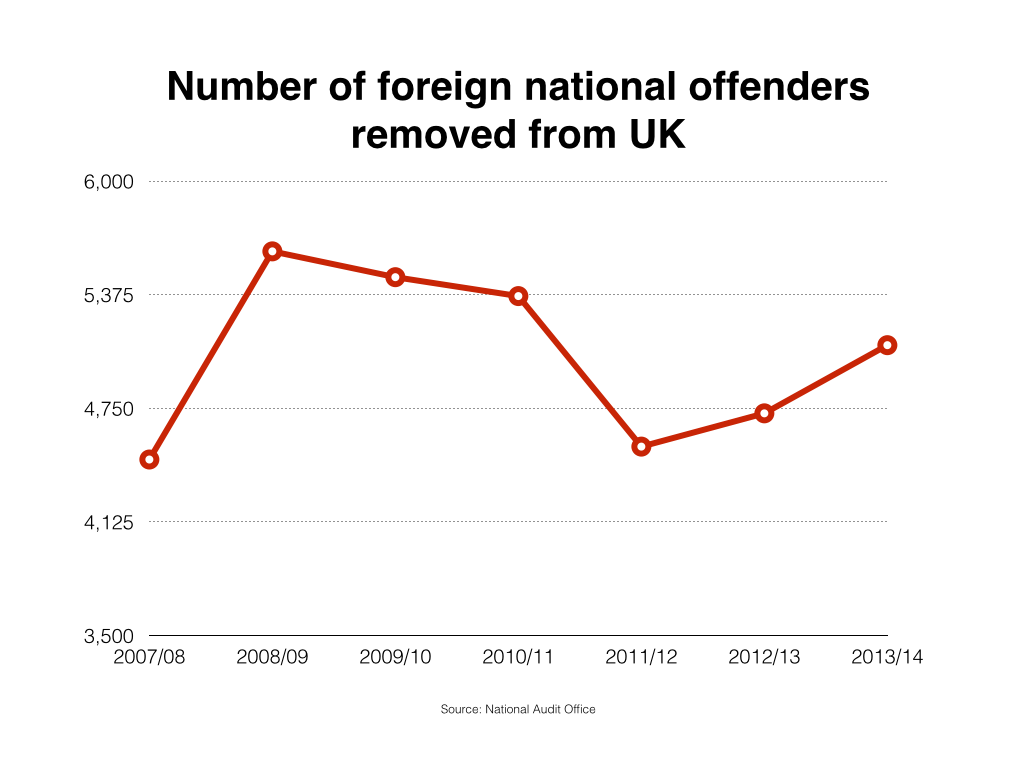

To begin with, according to the National Audit Office, half of foreign national offenders in prison in 2013-14 originated from European Union countries. If they seek to resist deportation they would rely on EU law rather than human rights law as it offers greater (but still far from absolute) protection against removal.

Some other foreign criminals occasionally resist deportation by relying on the UN Convention Relating to Refugee Status (Refugee Convention) or human rights grounds other than private and family life (primarily Article 3 ECHR, the absolute prohibition on torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment).

Such cases are often portrayed in the media as being allowed under human rights laws or the Human Rights Act when this is not true.

The Learco Chindamo case is one famous example. It succeeded on EU law grounds rather than under human rights law. One case in which I was involved succeeded under the Refugee Convention but was reported by the The Daily Mail and The Telegraph as a human rights case. The actual judgment is available here. Douglas Carswell, back then still a Conservative MP, was reported as saying in response to the case

Until we have freed ourselves from the European Convention on Human Rights, these sorts of basket-case decisions will carry on happening thick and fast.

In another case, reported on Free Movement, a judge was photographed outside his home and vilified by The Daily Mail for allowing an appeal on human rights grounds. “Senior immigration judge Jonathan Perkins said it would breach the 28-year-old’s human rights to deport Ali” the newspaper screamed. In fact the Home Office had conceded the case on Article 3 human rights grounds and the appeal went on to be allowed on refugee grounds.

There are no doubt some cases where serious foreign criminals succeed in resisting deportation in reliance on the right to private and family life. Without mandatory deportation that is inevitable: individual judges will consider all of the facts and evidence and may sometimes reach judgments with which some newspapers and politicians disagree. That is the function of an independent judiciary.

Is there a systemic “problem” that goes beyond such isolated and individual cases, though? The newspaper reports are often inaccurate anecdotes. What do the publicly available official statistics tell us?

How many foreign criminals win appeals under the Human Rights Act?

It is not possible to state definitively how many foreign criminals succeed in their appeals against deportation where the sole ground for their success was the hated Article 8 ECHR right to private and family life. As far as I am aware, the Government simply does not publish this information.

One has to wonder why this data is not available, particularly given the importance that politicians and civil servants say they attach to the issue. Without being able to measure a problem it is hard to devise an effective way of addressing it. It may be that there are insurmountable obstacles in the way of collecting the data, or it may be the a case that the data could be collected but is not. Or maybe the data is collected but is not published.

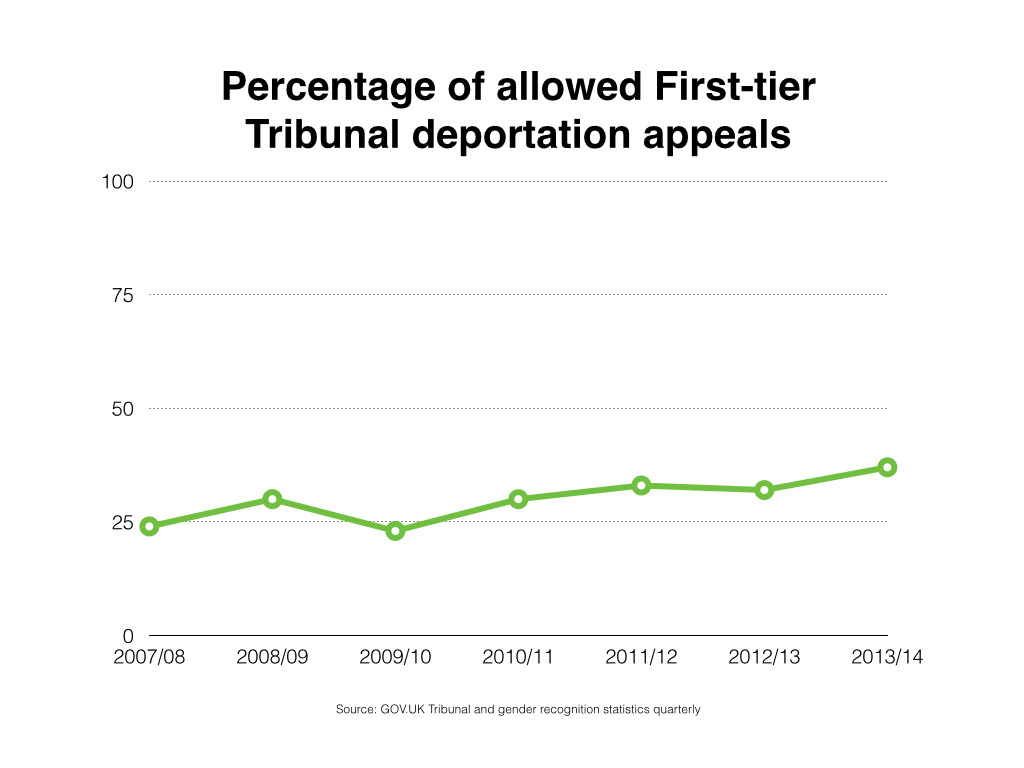

The LSE have estimated that between 2 and 8% of deportation appeals were allowed on Article 8 grounds in 2010. I’m not massively confident in the calculation because it involves mixing two sets of data, and in any event it is quite out of date.

Dominic Raab MP stated in a Parliamentary debate in January 2014 that the number of successful article 8 challenges to deportations by foreign criminals ranged from 200 to 400 a year and constitute 89% of all successful human rights challenges to deportation orders. The Freedom of Information request he relies on is not available as far as I am aware so it is not possible to check whether what he says is an accurate reflection of it. His numbers are certainly a lot higher than the LSE figures and much else he says on the Human Rights Act is demonstrably wrong.

The main series of quarterly immigration statistics do not tell us anything helpful on this issue. The best sources of information we have are the quarterly tribunal statistics and a recent report by the National Audit Office, Managing and removing foreign national offenders.

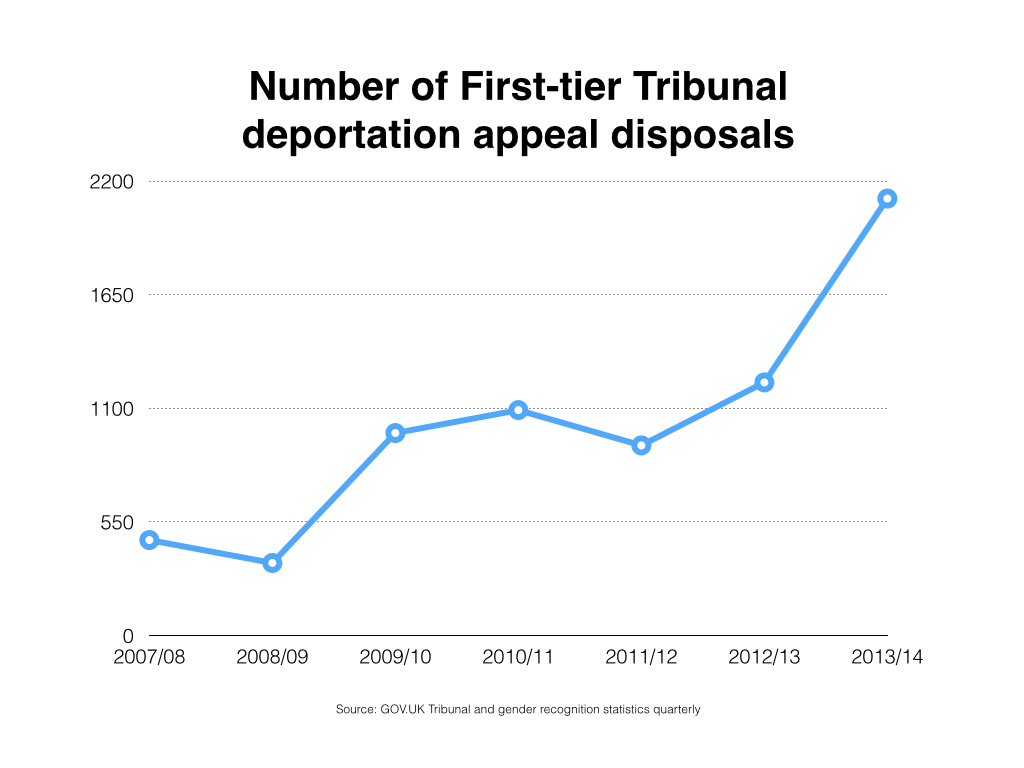

The tribunal statistics tell us how many deportation appeals there were and what percentage was allowed. They do not tell us on what basis the appeals were allowed, though. Also, the data in the tribunal statistics is for “deportation and other” cases, it varies between different series and it varies with that of the Home Office and the National Audit Office.

The NAO report suggests that only 1 in 7 foreign criminals succeeds in winning appeals in 2013. This is around 14%, which is a far lower number than that set out in the tribunal quarterly statistics. The NAO does not specify on what grounds the cases succeed. They do give us a breakdown of the top ten nationalities of foreign national offender in prison, though, which reveals that the top nationalities in 2013-14 were the Irish and Poles, neither of which group relies on human rights law if resisting deportation. It looks like around half of foreign national offenders in prison come from EU countries and would therefore rely on EU law rather than human rights law if they were batting against deportation.

It is the NAO report which tells us that there were fewer than 100 Home Office staff working on foreign national offenders in 2006. This had increased to 550 by 2010 and over 900 by 2014. During the same period the number of removals of foreign national offenders peaked at 5,613 in 2008-09 before falling back. The increase in resources thrown at the problem was not matched by commensurate improvement.

There is some suggestion in the NAO report that legal changes will enable the Home Office more easily to removal foreign national offenders. Some of this is true. The introduction of ‘deport first, appeal later’ provisions certainly reduces the scope for legal challenges in the UK, although as the next report we look at shows that is not always the real problem. The change from 17 to 4 grounds of appeal has no impact, though, given that the grounds still include human rights, refugee and EU law grounds.

Perhaps more revealingly, the NAO finds that a Foreign National Offender action plan was only introduced in 2013 and even now that it is seriously flawed: “the plan does not prioritise actions effectively and there are no clear links between actions, resulting change and impact on removal.” Further, “work is hindered by over-complicated arrangements in the Department” and “lack of joint working and administration errors have often led to missed opportunities for removal.”

Perhaps it is not the Human Rights Act that is at fault.

Other obstacles to removal of foreign criminals

In March 2014 Theresa May finally permitted publication of a report completed some months previously by the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, An Inspection of the Emergency Travel Document Process. The report is damning.

The report concerns forced removals generally rather than being specifically on foreign criminals, but the sample for the inspection included over 50 foreign national offender cases. The references in the report to “ETDs” are to Emergency Travel Documents; without these it is impossible to remove a person with no passport to another country because the person simply will not be admitted and instead will be bounced straight back to the UK. In his forward John Vine says

The Home Office was applying for too many ETDs that had little prospect of being used, rather than focusing resources on cases where re-documentation was likely to result in removal. This is a long- standing issue. I found that the Home Office had not used several thousand ETDs that had already been agreed by embassies. In some instances, these agreements dated back more than ten years.

My sample showed that many such cases were not being actively progressed, leaving individuals’ immigration status unresolved. This is unacceptable.

The management of the removals process is revealed to be a shambles. 78% of those in the inspection sample were not even being actively caseworked. Vine highlights the detention of foreign national offenders for long periods because they cannot be issued with ETDs either because of their own non-compliance or because the embassy of their country will not comply. On average, immigration detention was 523 days for the former and an astonishing 755 days for the latter. Neither issue is anything to do with the resisting removal on the basis of the Human Rights Act.

So none of these data sources — the tribunal statistics, NAO report or Chief Inspector report — points at the Human Rights Act being the significant obstacle to deportation of serious criminals that successive Governments have found it convenient to portray.

Legal protections now weaker than before the Human Rights Act

The law on deportation is now far stricter than in the era before the advent of the Human Rights Act.

Before 2006 the immigration rules conferred a general discretion to deport or not as long as certain relevant considerations were taken into account. The relevant paragraph of the rules, paragraph 364, read as follows:

… in considering whether deportation is the right course on the merits, the public interest will be balanced against any compassionate circumstances of the case. While each case will be considered in the light of the particular circumstances, the aim is an exercise of the power of deportation which is consistent and fair as between one person and another, although one case will rarely be identical with another in all material respects. … Before a decision to deport is reached the Secretary of State will take into account all relevant factors known to him including:

(i) age;

(ii) length of residence in the United Kingdom;

(iii) strength of connections with the United Kingdom;

(iv) personal history, including character, conduct and employment record;

(v) domestic circumstances;

(vi) previous criminal record and the nature of any offence of which the person has been convicted;

(vii) compassionate circumstances;

(viii) any representations received on the person’s behalf.

This was the system that had been in place since the 1970s and it continued uninterrupted when the Human Rights Act came into force in 2000. No foreign criminal resisting deportation really needed to rely on the Human Rights Act because the immigration rules offered better protection.

In 2006 this old fashioned and pragmatic British approach was replaced with a presumption in favour of deportation, followed in 2007 by supposedly “automatic” deportations under the UK Borders Act 2007. Contrary to popular misconception and contrary to the bizarre initial submissions by the Home Office, immigration judges sat up and took note of the change: see EO (Deportation appeals: scope and process) Turkey [2007] UKAIT 00062.

The UK Borders Act was mainly about process rather than outcomes; it introduced an unenforceable legal obligation on the Home Office to pursue deportation against any foreign national sentenced to more than 12 months in prison but it included exceptions for EU, human rights and refugee cases. This could just have easily been achieved with a policy instruction to civil servants or a change to the normal immigration rules. It did, though, signal to judges that greater weight was to be attached to the public interest in deportation, something that judges took on board and which is reflected in jurisprudence: see, for example, RU (Bangladesh) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2011] EWCA Civ 651.

The immigration rules were changed again in 2012 to introduce a sort of tariff system where residence of certain periods might save a person from deportation unless sentenced to more than 4 years in prison, in which case the only salvation was would be “exceptional circumstances”. The Immigration Act 2014 introduced further changes, introducing similar provisions into primary legislation and also introducing the “deport first, appeal later” system.

Judges apply these rules very carefully and in my experience it is very unusual indeed for a modern deportation appeal to be allowed on human rights grounds.

It is true that the European Convention on Human Rights prevents the UK from introducing mandatory deportation in all circumstances without regard to the impact on the individual concerned or their family. The Human Rights Act itself does not; such a law would have to be declared by judges to be incompatible with the ECHR under section 4 of the HRA but the law would still stand and be binding and judges would have to apply it.

What has happened over the last decade is that the old pre HRA approach to deportation which was flexible, unprescriptive and compassionate in nature has been replaced by a low level floor below which rights cannot be further reduced. The floor is provided by the European Convention on Human Rights.

What sort of cases might succeed on human rights grounds?

Dominic Raab MP, now the Minister responsible for replacing the Human Rights Act, has said that Strasbourg jurisprudence does not establish a right to resist deportation for foreign criminals and that it is our own British judges who are to blame because of the Human Rights Act. He should read Moustaquim v. Belgium, Boultif v Switzerland, Uner v Netherlands and Maslov v Austria as primers in basic human rights law on deportation. These cases are the European Court of Human Rights Grand Chamber decisions that establish the guidance that British judges take into account when considering deportation appeals. He should also read UK judgments such as R (On the Application Of Akpinar) v Upper Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) [2014] EWCA Civ 937, which show that UK judges have not applied these judgments slavishly.

Based on the Strasbourg cases, there are basically two situations in which a foreign criminal might potentially succeed in resisting deportation on human rights grounds:

- If the foreign criminal has been resident in the UK since childhood and is facing deportation to an essentially foreign country about which he or she knows nothing and the offence is not a super-serious one, such a person has a fighting chance of resisting deportation.

- If the foreign criminal has children and a partner in the UK the question becomes whether the family can be expected to relocate abroad, whether it is reasonable and proportionate for the family to be permanently split by deportation of the foreign criminal or whether the foreign criminal should be allowed to remain with his or her family in the UK.

My direct experience is that judges are highly sceptical when a foreign criminal asserts that he or she has a close relationship with his or her family in the UK. Strong evidence is needed to prove this and it only cases where the foreign criminal can establish a genuine and subsisting family life and genuine harm to the family that might potentially succeed.

If the foreign criminal is particularly vulnerable in some way then deportation might also potentially be a breach of a person’s human rights, but such situations are very rare indeed and the evidence would need to be very strong.

Some may legitimately object to these potential exceptions to deportation. But the point of human rights law has always been to provide the individual with rights that must be properly and individually weighed about the rights of others as a safeguard against tyranny. Laws of absolutes that brook no exception are anathema to human rights law.

One argument in favour of an unfettered and absolute power to deport foreign criminals that I personally do not consider a legitimate one is that foreign criminals are not entitled to a family life. The Conservative Party manifesto for the 2015 election refers to the “so-called right to family life” for example. Setting aside the issue of whether a foreign criminal sacrifices their right to a family life by committing a crime, this approach ignores the impact on the family members. Deportation of a parent is akin to bereavement, but it is potentially harder for the child to understand and come to terms with because the parent continues to exist but has been exiled by law rather than choice.

Such children are punished and their life chances irrevocably harmed because of their lack of foresight in having a foreign rather than British parent.

How did the current narrative on human rights and foreign criminals develop?

There was a sea change in media discourse on migration issues between 2004 and 2006. Prior to that, the obsession was with “bogus asylum seekers”, who were equated with economic migrants and with terrorists. The response to historically extraordinary numbers of asylum claims in the first part of the decade were fictional stories on asylum seekers eating swans and donkeys. By the middle of the decade, though, asylum claims were falling and there were two major developments, neither of which can had anything to do with the Human Rights Act.

Firstly, a number of new countries acceded to the European Union in 2004 and the UK elected not to impose restrictions on work by citizens of those countries. Famously, the numbers of Poles and others who came to the UK were higher than expected.

Secondly, it was revealed in 2006 that the Home Office had been simply ignoring the release of serious foreign criminals at the end of their sentences and the narrative changed. These criminals had been released into the community with no consideration at all of whether they should be deported. It wasn’t that the criminals were winning appeals in reliance on human rights laws; the Home Office, through sheer incompetence, simply forgot to try and deport them.

The Government response was twofold: grand reorganisation of the Home Office by creating an arms length agency responsible for immigration control and changes to the immigration rules then primary legislation to create a presumption of deportation. Neither response actually addressed the real issue, which was a simple one of mismanagement, but the changes were effective managing the media narrative. The media moved on from asylum to immigration and Europe generally, whether it be the European Union or the European Convention on Human Rights.

The smoke and mirrors continue to this day, as anyone will see who reads the National Audit Office and Chief Inspector reports on management of foreign criminals. It is not the Human Rights Act or the European Convention on Human Rights we should be blaming but incompetent management of the Home Office.

SHARE