- BY John Vassiliou

Can Hong Kong activists get political asylum in the UK?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleSimon Cheng, a former British consulate worker in Hong Kong, was allegedly abducted by the Chinese authorities during a trip to mainland China and tortured for fifteen days in August 2019. His account is terrifying. Cheng was a vocal supporter of the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement. He was recognised as a refugee by the UK in June 2020.

Cheng is a British National (Overseas) citizen and also, I assume, a citizen of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. Hong Kong citizens have their own passports, distinct from the rest of China, known as HKSAR passports. Both BNO and HKSAR passport holders are entitled to visit the UK for up to six months without having to get entry clearance in advance. They can get on a plane and just turn up at the border.

The prominent pro-democracy activist Nathan Law has done just that, arriving in London this week. Law told Free Movement that he has not made any plans to claim asylum here yet. But if he did, what would be his chances — or those of any activist fleeing Hong Kong for fear of reprisals from the Chinese government — of following in Cheng’s footsteps and becoming a refugee?

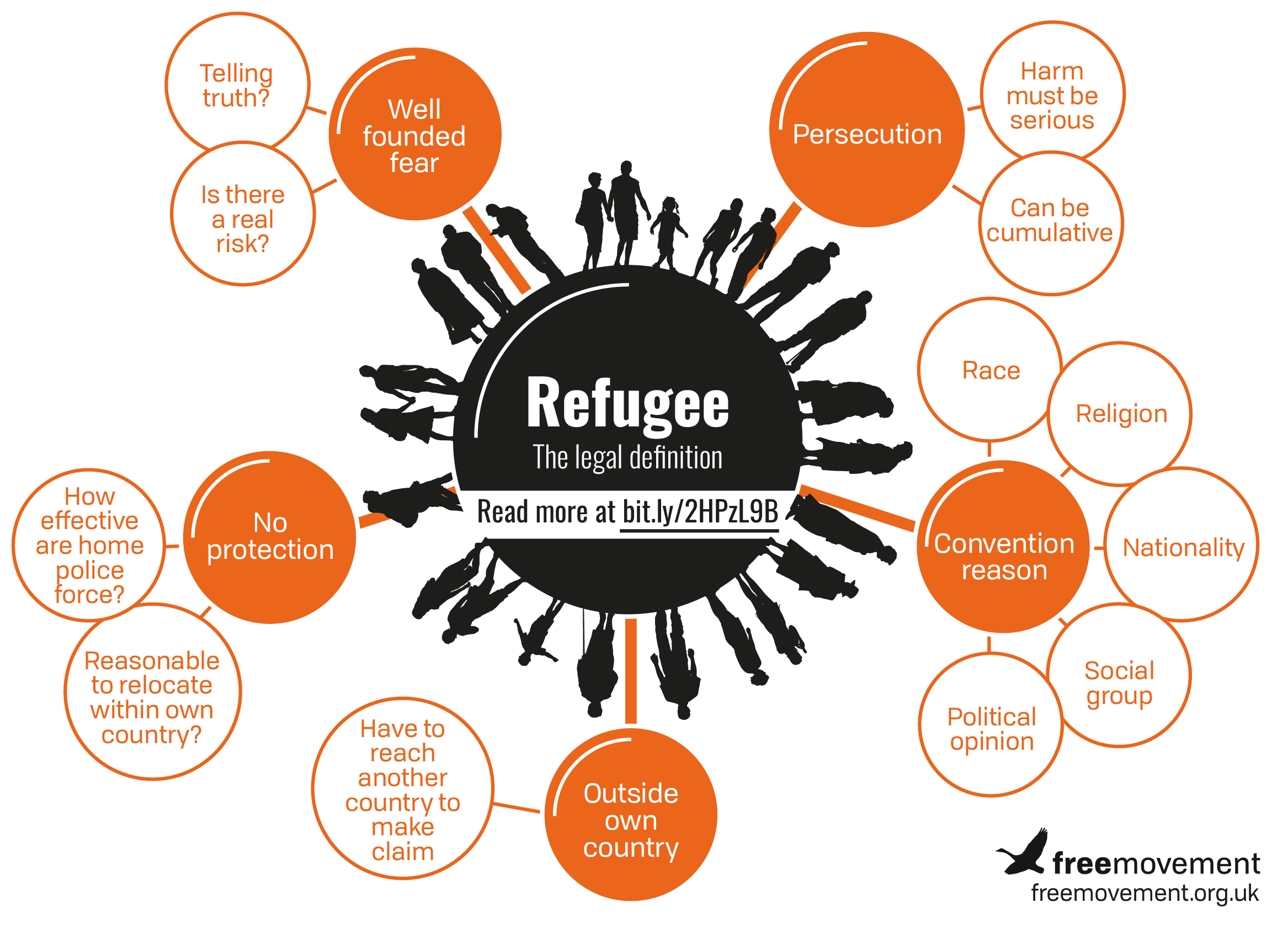

The legal definition of a refugee

To be granted asylum in the UK, a person must satisfy the Home Office that they meet the definition of a “refugee”. The legal definition of the term “refugee” is set out at Article 1A(2) of the UN Refugee Convention, which defines a refugee as a person who:

owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to return to it.

All of these conditions need to be met for the person to be considered a refugee.

Perhaps more crucially, they also need to be believed by the Home Office. In February 2020, the Home Office published a Country Policy and Information Note on China: Hong Kong protests which dashed hopes of a lenient stance on asylum claimants.

With the passing of the new Hong Kong security law, however, a lot has changed since February.

Well-founded fear of persecution

Successful asylum applicants must establish that they have a well-founded fear of persecution for one of the five reasons set out in the Refugee Convention. For Hong Kong political activists, any persecution will likely be based on their political opinion.

A well-founded fear is forward-looking. Participants in the pro-democracy movement need not have already been tortured or persecuted to have a well-founded fear of it in future. Experiences like Cheng’s do go a long way towards establishing a credible claim; evidence of past persecution can be a powerful indicator of likely future treatment.

Those who have not suffered like Cheng would have to explain to the Home Office why they fear they will be targeted and what they fear will happen to them. This is much harder to explain if it has not already occurred, but it is not impossible, especially if supported by credible reports of comparable incidents.

The hardest thing for pro-democracy protestors will likely be persuading the Home Office that they are known to the Chinese authorities and at risk. Many will have attended protests, and many may also have been arrested, but for the Home Office these facts alone are unlikely to be sufficient to establish a well-founded fear of persecution. The February guidance document says:

2.4.6 Where a person was (or was perceived to be) involved in the protests, they are unlikely to be able to establish a well-founded fear of persecution.

2.4.7 Over 4000 people have been arrested since protests began with the vast majority being arrested while taking part in demonstrations. Whilst the authorities have, at times, used some heavy-handed responses to violent protests, the ‘targets’ appear to be random. The objective country information does not suggest that the authorities have the will or the means to specifically identify people who may have taken part and single them out for mistreatment during protests (see Response to protestors).

2.4.8 There have been a small number of incidents of people being arrested while receiving treatment for protest-related injuries. However, aside from high profile activists, the objective country evidence does not suggest that the Hong Kong authorities are actively targeting those who may have been involved in the protests or subjecting them to treatment which is sufficiently serious by its nature and repetition to constitute persecution or serious harm (see Response to protestors).

Cheng, as a high profile activist, fit the bill and was able to establish that he had a well-founded fear of persecution for reason of his political opinions. Law, a former elected representative who recently testified to the US Congress about the new security law , would also have a strong case in this respect.

Lower-profile activists would have to explain why they believe they will now be persecuted as a consequence of the new law, particularly if they have been living safely in Hong Kong without persecution to date. Each person’s story and fear will be unique, and the Home Office would assess these case by case.

Persecution not prosecution

The Home Office guidance reminds readers that

2.4.10 A person fearing the legal consequences of being (or being perceived to be) involved in the protests would fear prosecution not persecution.

It is however possible for prosecution to amount to persecution. Whether prosecution under the new security law would reach the threshold of persecution in the eyes of the Home Office is hard to say at this stage, as we are still waiting to see exactly how the new law is going to be applied. But initial reports about the extent of the new law are worrying, and prosecution under its provisions may well point towards persecution.

In Cheng’s case, he provided a compelling account of his detention and torture by the Chinese authorities which satisfied a Home Office caseworker of his credibility. This treatment was not prosecution, it was persecution. Applying the lower standard of proof for asylum claims, there was a “reasonable degree of likelihood” or “real risk” that he would face further persecution if returned to Hong Kong.

There is no set definition of persecution, but torture of the type described by Cheng is undoubtedly it.

Unable or unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country

Hong Kong may be a distinct region with its own passports, laws and currency, but it is still part of China. The newly imposed national security law grants Beijing direct powers to crack down on political protest in Hong Kong. If Cheng’s fear was found credible, then because the persecution would be perpetrated by the Chinese state, Cheng would have been both unable and unwilling to avail himself of the protection of the Hong Kong and Chinese authorities. Indeed he stated so in November 2019 in a public statement issued on Facebook.

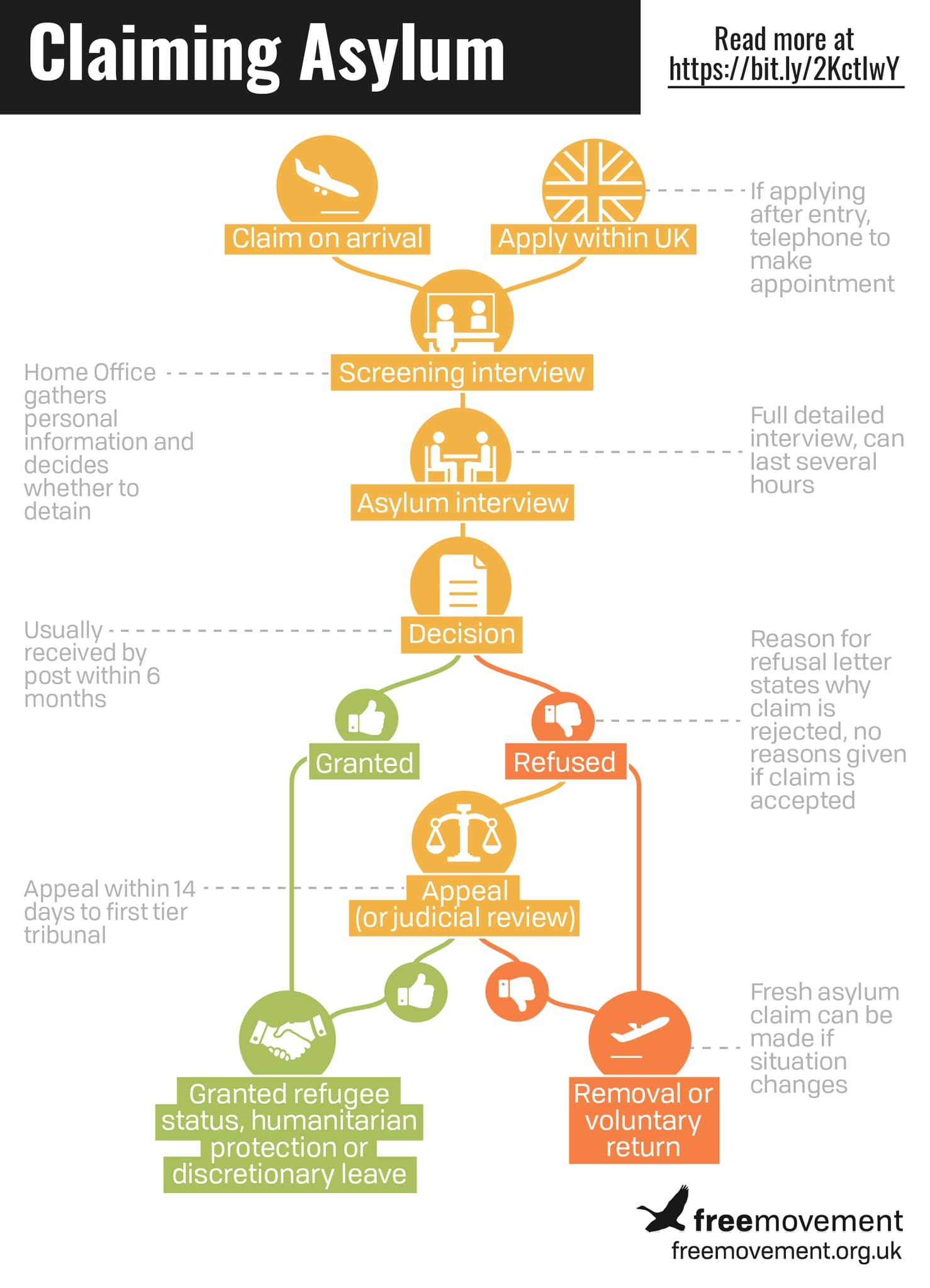

It is not possible for asylum claims to be lodged from outside of the UK. Cheng was in the UK when he claimed asylum.

This is where a BNO or an HKSAR passport would prove invaluable: such a passport allows the holder to embark on a journey to the UK and to either enter as a visitor or seek asylum at the border if that is the person’s intention. Many people around the world are not so lucky; they need to obtain some type of visa in advance of their departure for the UK.

Law, who does not have a BNO passport, arrived on what must have been a HKSAR passport and can stay for up to six months as a visitor. He would be entitled to claim asylum at any point during that period, simply by calling the Home Office. Any claim should, however, be made at the earliest possible opportunity. Failure to apply promptly can be held against an asylum applicant, as a point undermining their credibility, under section 8 of the Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants, etc.) Act 2004 and paragraph 339L of the Immigration Rules. More on credibility below.

Refugee status

Having satisfied the Home Office that he met the definition of a refugee, Cheng was granted refugee status. He will receive five years of limited leave to remain in the UK after which he will be eligible to apply for indefinite leave to remain. He will be able to settle in the UK during this time with the right to work, study, and claim public funds if he needs them. If he travels back to Hong Kong or China during this time, or even renews his HKSAR passport (if he has one), he may jeopardise his status.

The asylum process

Hongkongers seeking refuge in the UK should think carefully before committing to an asylum claim. The process can be long, stressful, and isolating. The Home Office generally disbelieve you at every step. You can go through this yourself but you would likely need a lawyer by your side. Many asylum claims are rejected initially, with people often having to go through numerous court appeals before being recognised as refugees.

This can be a tough period of limbo. Asylum claimants are not permitted to work. Instead they are housed by the Home Office and provided a very meagre weekly allowance, unless they have their own savings to fall back on.

The asylum process can be a long and tiresome journey, often ending in disappointment, but if it is one you need to make, Cheng’s case has certainly shown that the Home Office is willing to grant refugee status to Hong Kong residents.

Few may have as compelling a case as Cheng, and fewer still will have been fortunate enough to have been employed by the British consulate in Hong Kong — a factor which will undoubtedly have added significant credibility to Cheng’s claim. My (perhaps cynical) view just now is that the Home Office is still only likely to consider granting asylum to particularly high-profile activists.

Credibility and evidence

I’ve mentioned credibility a few times as this is something that goes to the core of any asylum claim. If the Home Office thinks a claim lacks credibility (in other words, if officials think you are lying, making up, or embellishing a story) your claim will be refused, and it can be hard to recover from such findings. The Home Office has a 42-page policy document on assessment of credibility.

Credibility can be enhanced with good supporting evidence, if you have it. Anyone making the tough decision to leave their home and seek asylum should do their best to bring as much evidence as they can to back up their claims. In many cases, there will be no evidence, but if you have been arrested or detained by the police for political crimes and have evidence of this — for example in the form of police or court papers — bring it with you. If you received medical treatment afterwards, bring medical evidence. If there are relevant photographs or news stories identifying you online or in the media, keep them.

Everyone’s case and experience is different, so there is no one-size-fits-all set of evidence. Many people will have none, and that’s OK so long as your story is true and is believed. But generally speaking, if any relevant aspect of your claim can be backed up by a piece of evidence, bring it with you if you can.

Asylum or BNO visa?

BNO passport holders may well want to hold off on claiming asylum and wait to see exactly how the newly announced BNO visa shapes up. Such a visa may prove unaffordable or inaccessible to many but it will undoubtedly be a smoother path to UK settlement than the asylum process.

Of course, many of the protestors are young, and born after the 1 July 1997 cut-off for BNO eligibility. For them, the BNO visa will be out of reach, leaving an asylum claim as perhaps their only option for securing the right to live in the UK.

SHARE