- BY Colin Yeo

How is the government using its increased powers to strip British people of their citizenship?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleYesterday’s judgment in Aziz & Ors v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] EWCA Civ 1884 saw the Court of Appeal uphold the Home Secretary’s decision to use her power to strip members of a notorious Rochdale grooming gang of their British citizenship. The use of a power once reserved for national security cases to impose additional punishment upon serious criminals is new. It is worth reflecting on the implications and reviewing how we got here.

Until quite recently, the power to deprive a person of their British citizenship on the grounds of behaviour was almost moribund, having been used against perhaps a handful of Russian spies. But in July 2016 the Bureau of Investigative Journalism reported that Theresa May had as Home Secretary used the public good deprivation powers against dozens of people since taking office in 2010.

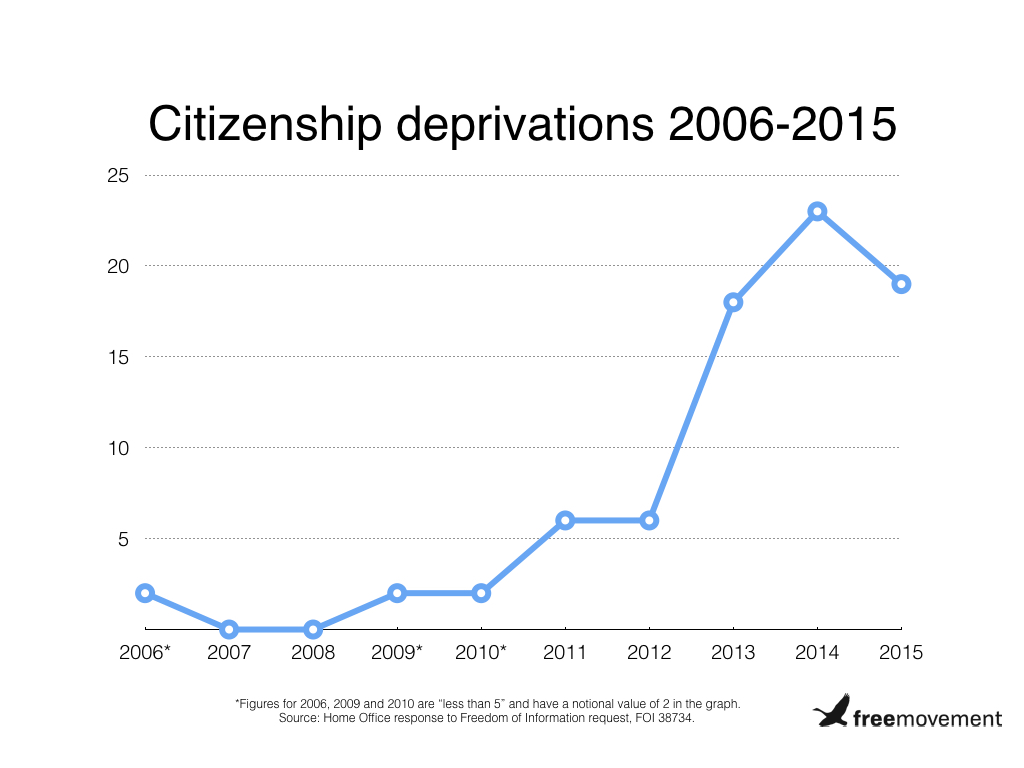

According to Freedom of Information requests by the author, 81 individuals were stripped of their citizenship using deprivation powers between 2006 and 2015. The chart below shows the trend. Of these, 36 were deprived of citizenship under the public good power specifically (the remaining 45 being for fraud, false representation or concealment of a material fact). It is the public good deprivation power that I want to look at in this article.

The legal constraints on this power have been significantly loosened over the years, and the Rochdale case shows that the Home Office is prepared to exercise it in circumstances other than those touching on national security, as has traditionally been the case. This would, if the start of a trend, be cause for concern — or at least some public debate.

Evolution of the power to strip British citizenship

The power to deprive a British citizen of their citizenship status has been widened so that it can be used against far less serious conduct than in previous years.

1948-2003: a high bar to meet, power rarely used

British citizenship was first put on a statutory footing by the British Nationality Act 1948. Before that there were no such thing as citizens, only subjects. British nationality law is now governed by the British Nationality Act 1981, and that is where we find the power to deprive a British citizen of his or her citizenship status.

The original incarnation of the deprivation power in the British Nationality Act 1981 was very similar to the equivalent power under the British Nationality Act 1948, which was itself very similar to the equivalent power first introduced by the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914, and therefore can be said to have been in place for decades.

Originally the BNA 1981 set out what is now the public good deprivation power as follows, in section 40(3):

Subject to the provisions of this section, the Secretary of State may by order deprive any British citizen to whom this subsection applies of his British citizenship if the Secretary of State is satisfied that that citizen—

(a) has shown himself by act or speech to be disloyal or disaffected towards Her Majesty; or

(b) has, during any war in which Her Majesty was engaged, unlawfully traded or communicated with an enemy or been engaged in or associated with any business that was to his knowledge carried on in such a manner as to assist an enemy in that war; or

(c) has, within the period of five years from the relevant date, been sentenced in any country to imprisonment for a term of not less than twelve months.

The power only applied to those who acquired British citizenship by registration or naturalisation. British citizens by birth could not be deprived of their citizenship. In practice, deprivation powers were not used at all between 1973 and 2002.

Subsection 40(5) then stated that the power should not be used unless the Secretary of State was satisfied that it was not conducive to the public good that the person should continue to be a British citizen and that the person would not be rendered stateless. At that time, the public good was more akin to an additional protection and restraint on exercise of the power than a threshold for deprivation.

2003-present: fewer constraints on deprivation power, increased use

The Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 substituted an entirely new version of section 40. In this 2002 version, deprivation on the basis of behaviour was set out at section 40(2) and came into force on 1 April 2003:

The Secretary of State may by order deprive a person of a citizenship status if the Secretary of State is satisfied that the person has done anything seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of—

(a) the United Kingdom, or

(b) a British overseas territory.

This version of section 40 also removed the protection against deprivation for individuals born British. This removed the discrimination between citizens by naturalisation and birth, but by levelling down the protection available rather than levelling up.

Section 40(2) was amended again by the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006 to the current version. The public good deprivation power in the new section 40(2) now provides:

The Secretary of State may by order deprive a person of a citizenship status if the Secretary of State is satisfied that deprivation is conducive to the public good.

This test of “conducive to the public good” represents a noticeably more relaxed standard compared to previous versions. As we have seen, the easier legal test has coincided with a marked increase in the number of deprivations actually carried out.

Power to render people stateless

In addition, the Immigration Act 2014 added a new section 40(4A), which allows deprivation even where it might cause statelessness. That had never previously been the case.

As of 28 July 2014, it is possible to deprive a person of British citizenship and make him or her stateless if three conditions are met:

- he or she acquired citizenship by naturalisation

- the higher test of conduct “seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the United Kingdom, any of the Islands, or any British overseas territory”

- the Secretary of State has “reasonable grounds” for thinking that the person can acquire citizenship of another country

There is a requirement to serve written notice on a person, but regulations permit the Home Office to do this by serving notice on a last known address in the United Kingdom. This enables lawful deemed service on a person’s address while he or she is outside the UK and therefore unaware of service.

Examples of British citizens stripped of their citizenship

Reported citizenship deprivation cases typically involve alleged Islamic extremists alleged to be personally involved in terrorism-related activity. All but the final two of the reported cases involving use of the public good deprivation power involve activities which engage questions of national security. These are of the character of actual or potential crimes against the state. The most recent of the cases, Ahmed, Aziz and Pirzada, are of a different character, involving instead serious crimes in the UK.

Cases involving national security

M2 (Deprivation of Citizenship : Substantive) [2015] UKSIAC SC_124_2014 involved an Afghan national who acquired British citizenship by naturalisation in 2011. He was accused of being a risk to national security because of family and personal connections to prominent international terrorists.

In K2 v the United Kingdom (application no. 42387/13) the claimant had arrived in UK as a child from Sudan and naturalised as British in 2000. It was alleged that he was involved, in Somalia, in terrorism-related activities linked to Al-Shabaab.

S1, T1, U1 & V1 v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2016] EWCA Civ 560 involved four members of a family were all deprived of their citizenship on the basis they were active members of a proscribed terrorist organisation, Lashkar-e-Tayibba, and were supporters of Al Qaeda.

The case of Pham v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2015] UKSC 19 concerned a Vietnamese national who entered the UK as a child with his family and naturalised as British in 1995. At 21 he converted to Islam. Between December 2010 and July 2011 he was in Yemen, where, according to the security services but denied by him, he was said to have received terrorist training from Al Qaida. The security services assessed that at liberty he would pose an active threat to the safety and security of the UK.

More recent cases involving serious crime

The first reported case to involve issues not engaging national security was Ahmed and Others (deprivation of citizenship) (Pakistan) [2017] UKUT 118 (IAC). The appellants had acquired British nationality by naturalisation and retained their Pakistani nationality; they were dual nationals. Often referred to as the Rochdale gang, they had been convicted of the trafficking of children for sexual exploitation, rape, conspiracy to engage in sexual activity with children and sexual coercion. Their sentences ranged from six to 19 years’ imprisonment. The sentencing judge highlighted the scale and gravity of the offending, the protracted period involved (2008 – 2010), the ages of the victims — they were young teenagers — and the factors of callous, vicious and violent rape, humiliation and financial gain.

Ahmed reached the Court of Appeal as Aziz [2018] EWCA Civ 1884, Mr Ahmed himself having dropped out of the litigation. One of the remaining grounds of appeal was that the Secretary of State was bound to apply her deprivation powers in line with her own policy on the matter, which says that “conduciveness to the public good means depriving in the public interest on grounds of involvement in terrorism, espionage, serious organised crime, war crimes or unacceptable behaviours”. It almost succeeded, Lord Justice Sales holding that two of the Upper Tribunal’s three reasons for finding that the decision was consistent with the published policy were flawed. But the final reason stuck: “the crimes were plainly very serious and there was a sufficient element of organisation in the way they were committed to justify characterising the offending as participation in serious organised crime”.

A further example of issues not engaging national security but nevertheless prompting the Home Office to pursue deprivation action came in Pirzada (Deprivation of citizenship: general principles) [2017] UKUT 196 (IAC). The appellant was an Afghan national who had entered the UK in 2001 and claimed asylum. His claim was refused on the grounds of deception but he was granted limited leave. Before his leave expired he successfully applied for indefinite leave to remain. He then successfully applied for naturalisation at a British citizen in 2008. The appellant was convicted of various offences connected to posing as a qualified medical practitioner and sentenced to 17 months’ imprisonment. The rather confused decision to deprive him of British citizenship was taken on grounds of deception but principally related to matters occurring after the grant of naturalisation. In truth the decision was probably in substance one based on public good but where a Home Office official had failed to apply sufficient rigour to the case.

In all the other cases up to Ahmed/Aziz, the subject of the order was alleged to be a danger to national security and could therefore be classed as being involved in crimes against the state, the historical justification for banishment. The previous 1981 and 2003 thresholds for deprivation of citizenship would arguably have been engaged. Ahmed was the first case where the new, amended 2006 power has really been decisive in permitting deprivation to occur. It has taken a decade for the practice to catch up with the power. Whether it is the first in a new line of cases or genuinely an exception remains to be seen.

Nobody will shed a tear for the appellants in the Ahmed case and there are plenty of people who will support whatever additional punishment the authorities can lawfully impose in such circumstances. All the same, we hardly want to sleepwalk into a situation where powers designed to protect national security are routinely used against criminals without a debate on the desirability of such a system.

SHARE