- BY Sonia Lenegan

Briefing: is the modern slavery identification system in the UK being misused?

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Home Secretary has claimed (as have many of the last several of them) that the modern slavery identification process is “being misused” and has used this as a reason to carry out an “urgent review” of modern slavery laws. Assertions of misuse are incorrect. In reality, the opposite is true as the system is causing great harm to those it is supposed to protect. Ever since the Modern Slavery Act 2015 came into force, there has been a downward trajectory in the rights of survivors, particularly those within the immigration and asylum system.

The claims by the Home Secretary have been made in the context of legal challenges being made to those who are facing removal under the UK-France treaty. Two points need to be understood at the outset when considering modern slavery cases with UK-France removals.

The first is that a large proportion of people who have to make their way overland and across the Channel to the UK are trafficked along the way. Libya in particular is well known as a danger zone for this.

The second is that, for people who have just crossed the Channel to the UK and are detained, the Home Office is most likely to be the body responsible for identifying at the initial asylum screening interview whether there are trafficking indicators in a case that mean a person should be referred into the modern slavery identification process.

The Home Office’s own guidance acknowledges that survivors “may not recognise themselves as a victim of modern slavery or be reluctant to be identified as such” and “may initially be unwilling to disclose details of their experience or identify themselves as a victim for a variety of reasons”. The situation in which people are expected to disclose their experiences of trafficking and slavery are when they have just made the terrifying journey across the Channel, followed by immediate detention without legal advice. This is not even remotely conducive to disclosure and discussion of these topics.

It is also easy to believe that Home Office may be disinclined to make these referrals, given their priority is not to identify and protect victims but to get as many people on planes to France as possible. This view is supported by situations where we see the Home Office rejecting accounts of forced labour as well as imprisonment and exploitation in Libya, all of which strongly indicate that there has been trafficking, so that they can try to rush people onto a plane.

Luckily for the Home Office, the people they are targeting are in detention and it is incredibly difficult to access quality legal advice before a negative trafficking decision and a decision to remove are made. This is a particular problem where specialised knowledge of trafficking issues is required, which may be lacking from some of the legal providers on the detained duty advice scheme. Anyone looking at these issues should also read my explainer on how the system has been designed by the Home Office to try to prevent people raising effective claims which is why cases are sometimes heard close to removal.

This briefing only looks at the position and statistics relating to adults.

How does the modern slavery identification process work?

The first stage is that certain factors that indicate a person may have been trafficked need to be identified. This will usually come from the person’s account, but they of course need to be asked the right questions in the right (supportive and safe) environment.

On recognition by someone of these trafficking indicators, a potential modern slavery survivor then has to be referred, either by the Home Office, or by certain designated professionals into the protection system. These are called ‘first responders’ and a list of the organisations is published. Immigration lawyers cannot do make the referral themselves, nor can many NGOs who work to support survivors. The protection system is called the ‘national referral mechanism’ (NRM) and adults must consent to a referral.

Next, one of the two competent authorities, both part of the Home Office, must decide whether there are ‘reasonable grounds’ to think the referred person is a victim of modern slavery. The two bodies are the misnamed ‘single competent authority’ (SCA) and the ‘immigration enforcement competent authority’ (IECA). The latter was only created in 2021. As is indicated by the name, it has more of a focus on people without secure immigration status, including people who are detained or in the asylum inadmissibility process.

If the person receives a positive ‘reasonable grounds’ decision then consideration of their claim will move to the next stage. This is whether there are ‘conclusive grounds’ for thinking they are a victim of modern slavery and this is the final stage of the identification process.

The person will also be given a period of 30 days following the positive reasonable grounds decision for “recovery and reflection”. During this period they cannot be removed from the UK unless a disqualification decision is made. This is set out at 8.20 of the guidance and reflects article 10(2) of ECAT.

Negative decisions at either stage cannot be appealed but it may be possible to ask for a reconsideration of the decision or else seek judicial review where appropriate. Access to the reconsideration process is important because it allows for new evidence to be provided, in circumstances where it is often not possible to provide full evidence before the initial reasonable grounds decision is made. This is because the Home Office has set a high evidential threshold, which is extremely difficult to meet within the given timescales particularly where access to quality legal advice is not guaranteed.

Recognition as a victim of modern slavery does not mean that a person will automatically be granted leave. It may be relevant for an asylum claim.

2021: introduction of the immigration enforcement competent authority

In March 2021, former Home Secretary Priti Patel made evidence free assertions of – you’ve guessed it – “an alarming rise in people abusing our modern slavery system” and promised a review of the government’s modern slavery strategy. In November 2021 a second competent authority was introduced through changes to the modern slavery statutory guidance.

The new body was called the immigration enforcement competent authority and it was set up to deal with NRM referrals from the following groups:

- All adult Foreign National Offenders (FNOs) detained in an Immigration Removal Centre.

- All adult FNOs in prison where a decision to deport has been made.

- All adult FNOs in prison where a decision has yet to be made on deportation.

- Non-detained adult FNOs where action to pursue cases towards deportation is taken in the community .

- All individuals detained in an Immigration Removal Centre (IRC) managed by the National Returns Command (NRC), including those in the Detained Asylum Casework (DAC) process.

- All individuals in the Third Country Unit (TCU)/inadmissible process irrespective of whether detained or non-detained.

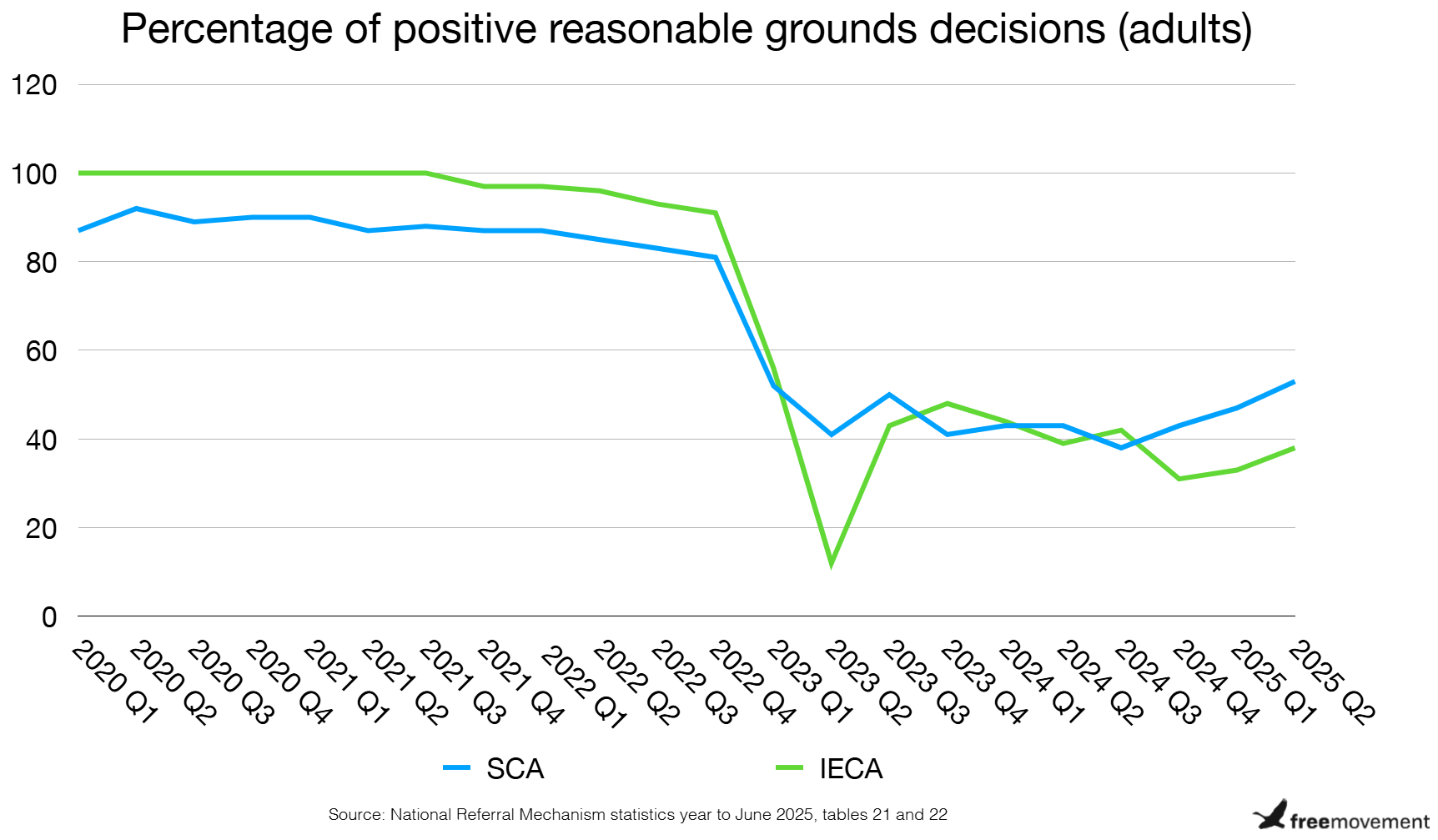

Concerns were raised from the outset at the prospect of immigration enforcement deciding modern slavery cases. In November 2022 I said that I had expected the IECA to be a “refusal factory”. In fact, we can see from the below that there was not much of an immediate impact at the reasonable grounds stage of the process. The big drop at the beginning of 2023 comes from the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, which I will get to next.

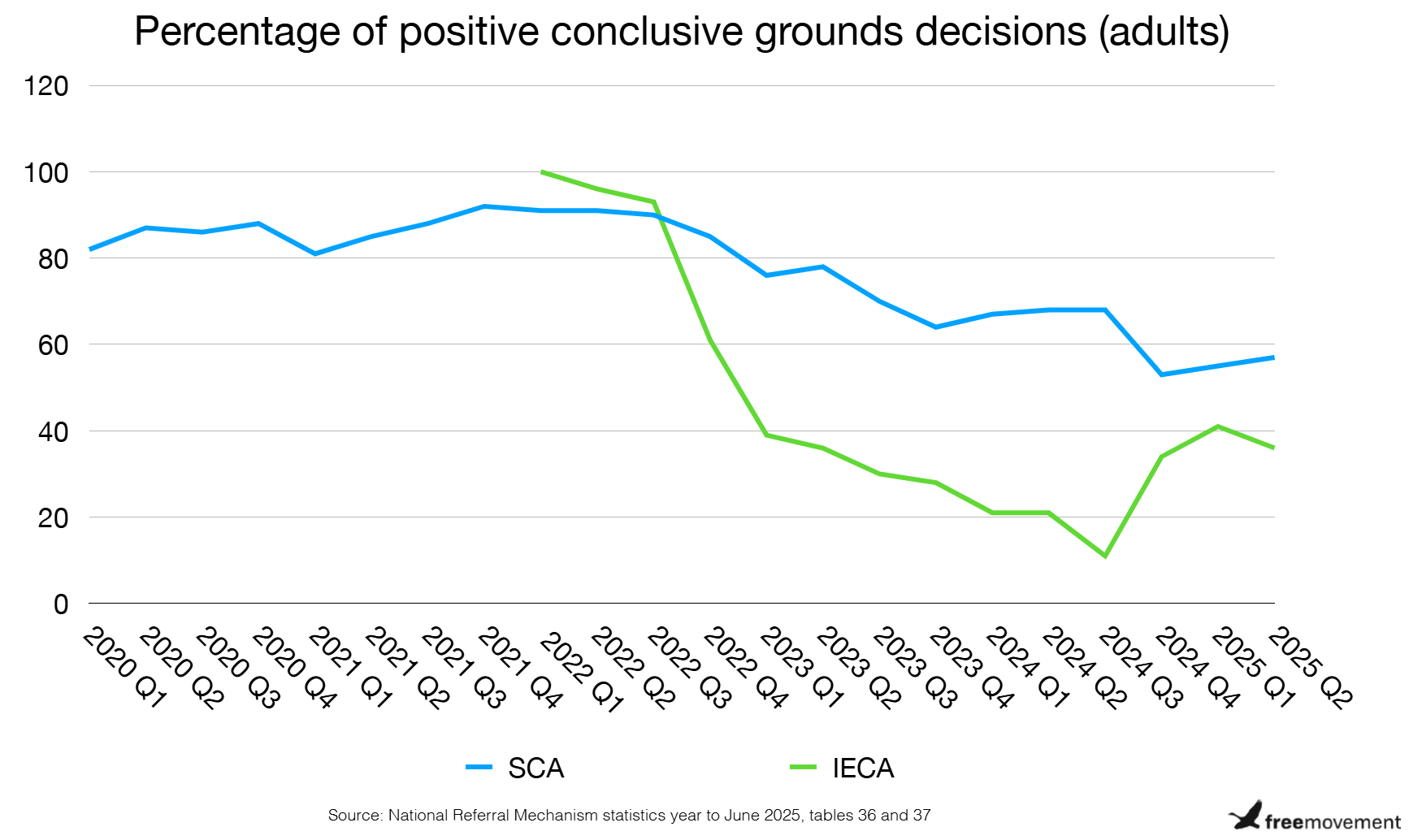

The IECA did have an impact on the grant rate at conclusive grounds stage, as we can see from the below that this had dropped to 61% in the last three months of 2022.

Increase in negative decisions following Nationality and Borders Act 2022

A few days after the former Home Secretary’s assertions about “abuse” of the system in March 2021, the New Plan for Immigration was published and a six week consultation period opened. This was the precursor to the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 which received Royal Assent in June 2022.

The relevant provisions of the Act on modern slavery were brought into force on 30 January 2023, making several damaging changes. This included severe limitations on the circumstances where a confirmed victim could be granted leave, in circumstances where data showed that only 7% of confirmed victims had been granted leave to remain in the five years from April 2016 to June 2021. Provisions were also brought in for people to be excluded from protection on “public order” or “bad faith” grounds.

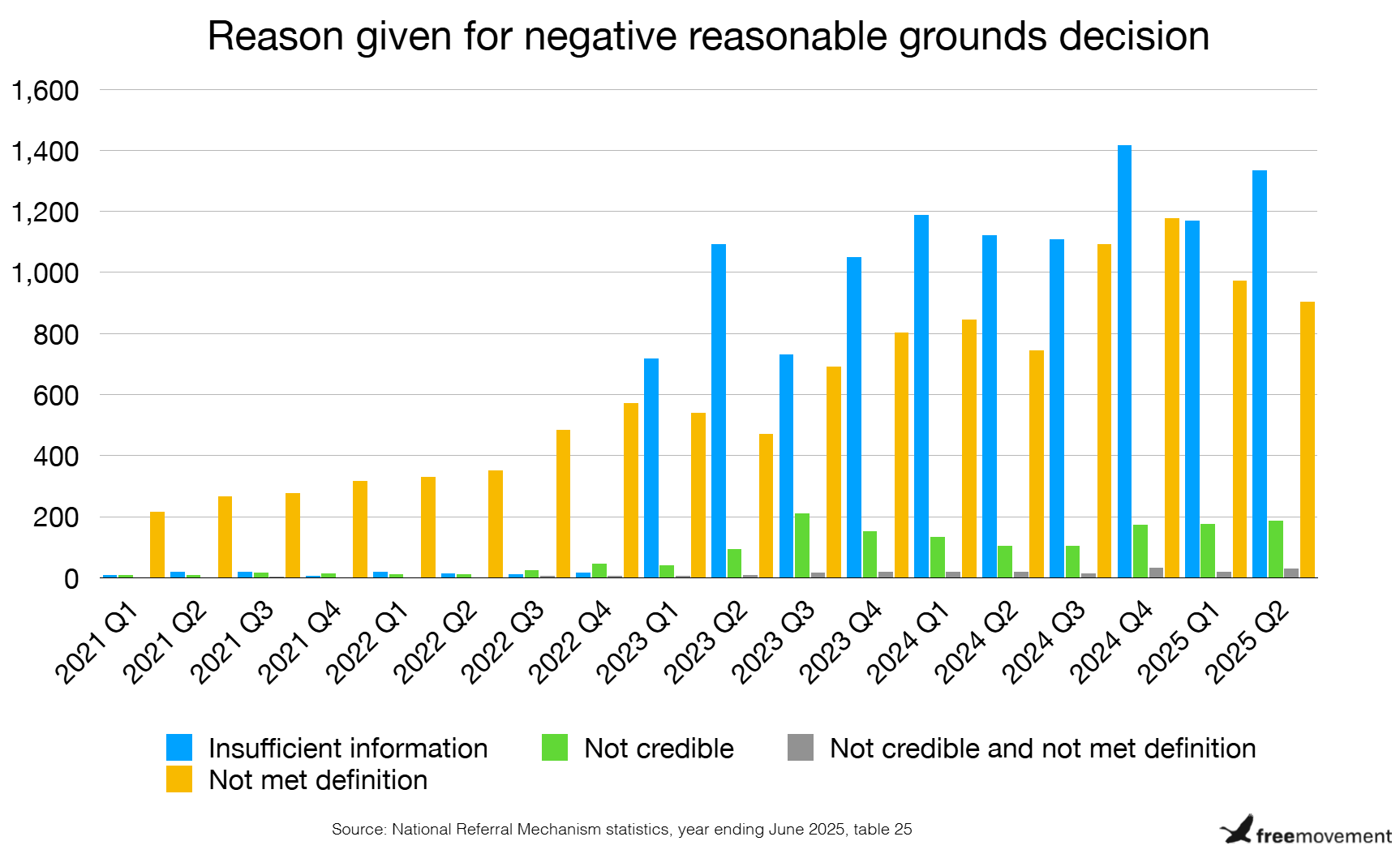

The modern slavery statutory guidance was also amended on the same date, to make additional changes including a requirement for “objective evidence” in the form of expert reports, witness statements and police reports. Survivors who were unable to provide this were given a negative reasonable grounds decision.

That resulted in a plummeting rate of positive reasonable grounds decisions as seen in the table above. This unreasonable requirement was quickly successfully challenged, with the Home Secretary conceding the point before the matter went to a full hearing, and issuing amended guidance in July 2023.

Despite this, we can see that since January 2023, the most common reason for a negative reasonable grounds decision to be made is that there is insufficient information.

It is important to note here that the target for these reasonable grounds decisions is five working days, a deadline which makes it practically impossible to obtain and submit the evidence that is required to obtain a positive decision. It is even more difficult for those who have just arrived across the Channel and are being detained without the ability to quickly access quality legal advice from lawyers who understand what the Home Office expects by way of evidence. Navigating this process without legal assistance is almost guaranteed to lead to a refusal.

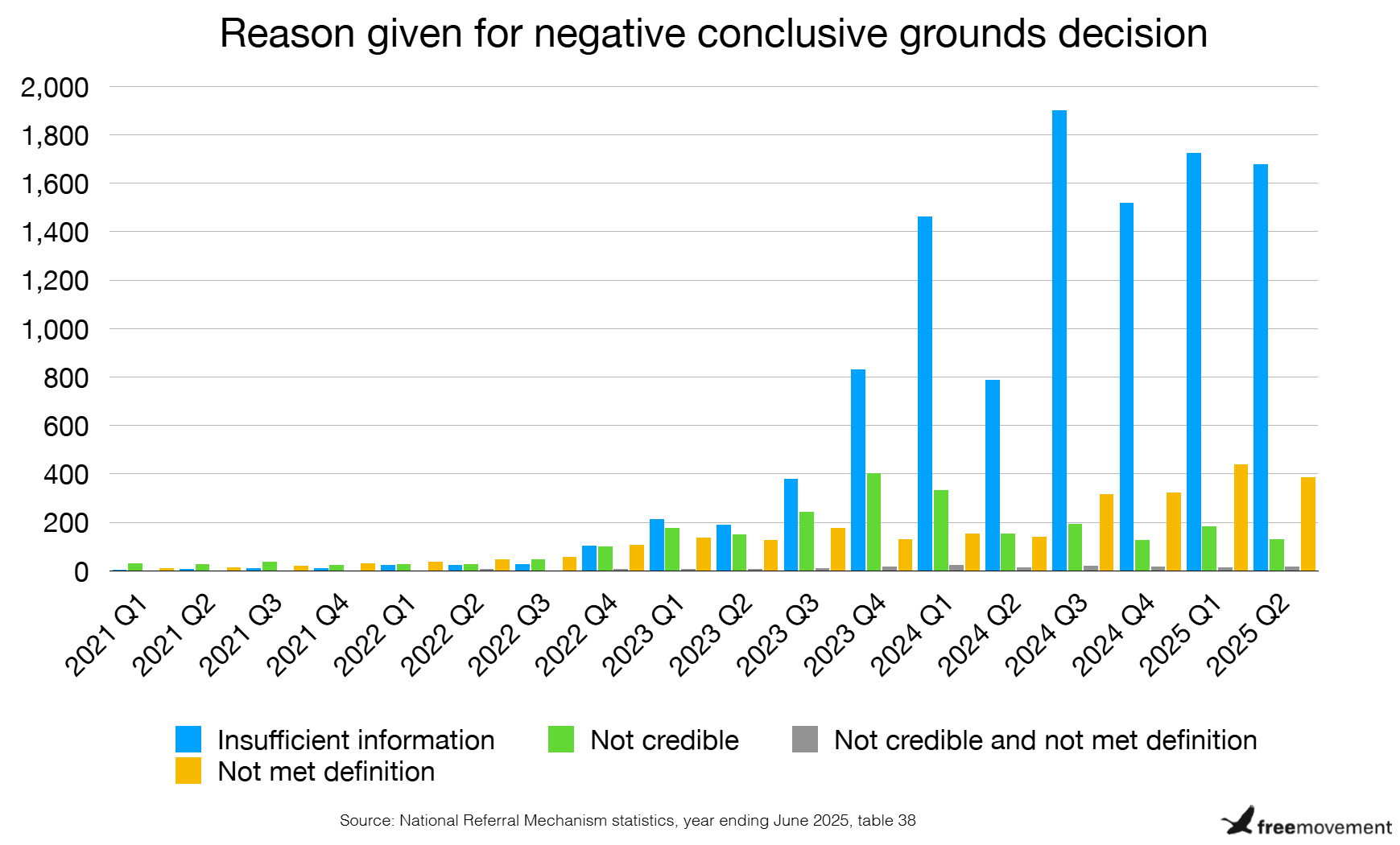

An even higher proportion of negative conclusive grounds decisions are based on there being insufficient information.

Quality of decisions and the importance of the reconsideration process

As is the case elsewhere in the Home Office, concerns about the quality of decision making are rife. In December 2024 the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration published a report following an inspection of the IECA. He said:

In light of the significant increases in negative outcomes at both stages of the NRM process, I would have expected the IECA to have shown greater interest in ensuring, and being able to demonstrate, that it was making ‘right first time’ decisions, especially given the life-changing nature of NRM decisions. However, the quality assurance regime, in particular, did not take sufficient account of the potential impact on individuals of poor-quality decisions.

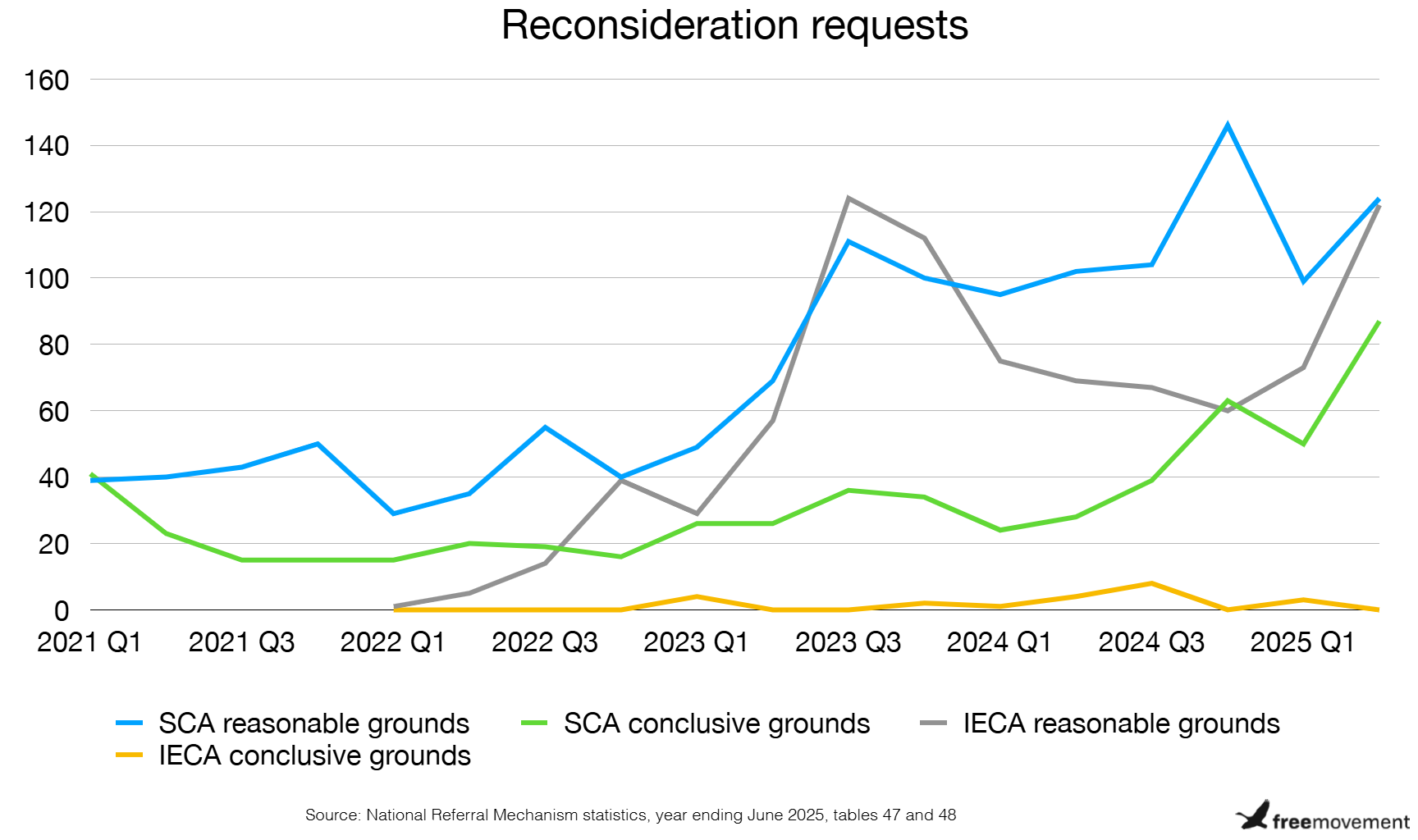

Given the huge increase in negative decisions and the concerns about the quality of the decisions, it is unsurprising to see a corresponding increase in reconsideration requests.

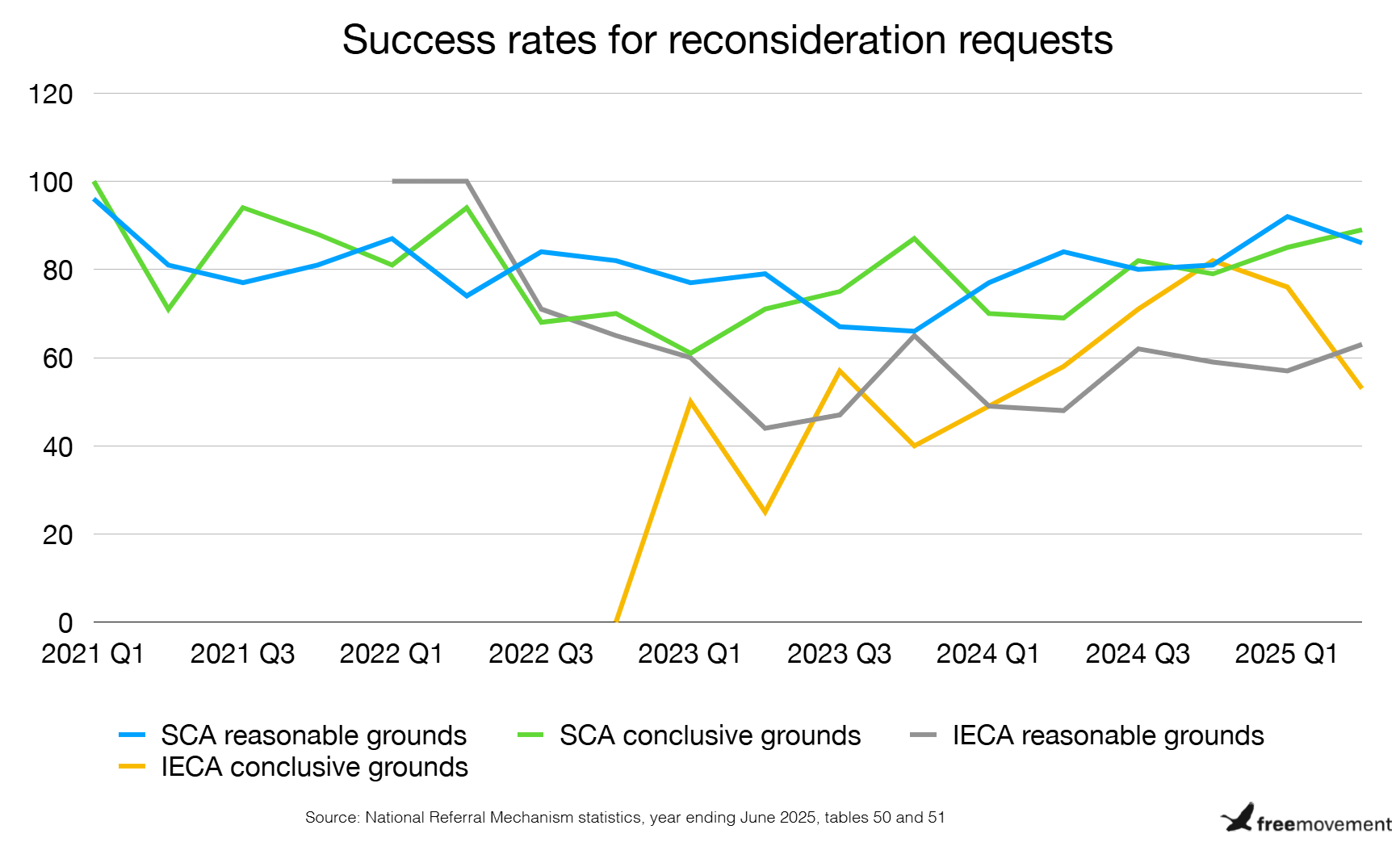

We can see that concerns about the quality of initial decisions are well-founded, as evidenced by the very high success rate of reconsideration requests.

The response to this very high success rate of reconsideration requests has not been to work to improve the quality of the decisions. The high success rate of reconsideration requests is even more notable given that on 12 February 2024 a one month deadline for reconsideration requests, including any new evidence was introduced. This deadline will only be extended in exceptional circumstances.

It is not unusual for a medico-legal report and possibly also a country expert report to be required in these cases to meet the high evidential threshold set by the Home Office, and it is very difficult to obtain these within such a short period of time.

Is there evidence that the system is being abused?

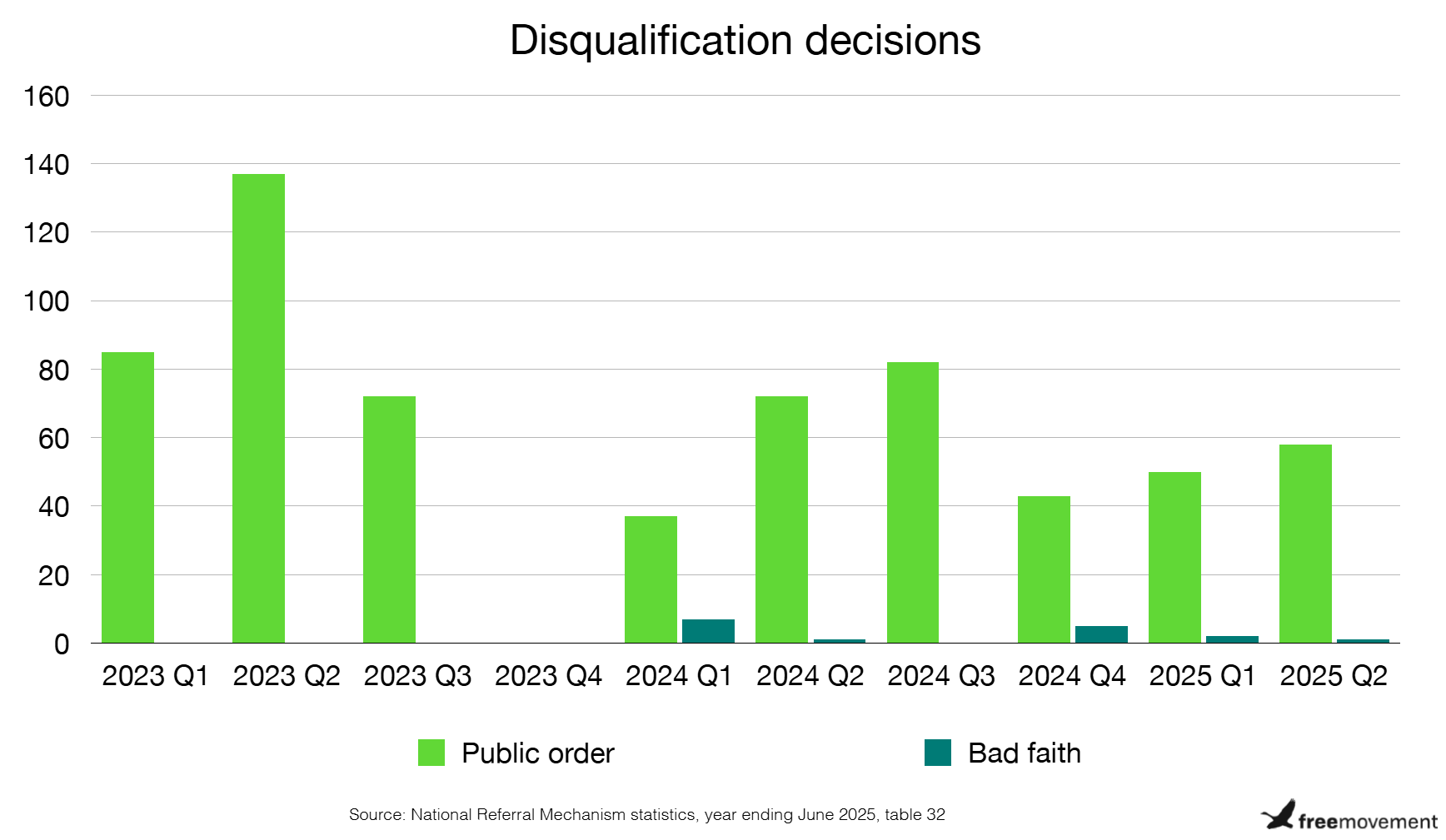

Another of the changes made by the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 was the introduction of disqualification decisions. After a positive reasonable grounds decision has been made, a potential victim can be removed from the rest of the NRM process on either public order or “bad faith” grounds.

“Bad faith” is defined in the guidance as being where the potential victim “or someone acting on their behalf, have knowingly made a dishonest statement in relation to being a victim of modern slavery”. As can be seen from the below, there has been a vanishingly small number of people disqualified on this basis.

Changes to the guidance for those affected by the UK-France agreement

I wrote up the change to the guidance affecting reconsideration of reasonable grounds decisions that was made in the evening of 17 September 2025, following the grant of interim relief in a removal case in the High Court. Essentially, in that case interim relief was granted because the Home Office had made a negative reasonable grounds decision and had told the claimant that he would have 30 days to seek reconsideration of that decision. The version of the guidance in force at that time also said that he would be able to do this within 30 days.

During the hearing, those acting on behalf of the Home Secretary confirmed that this reconsideration process could not take place if the claimant was in France, effectively acting as a barrier to removal. This was the basis on which the removal was stopped.

The guidance was then changed to say that the reconsideration process did not apply where the Home Secretary “intends to remove that individual to a country that is a signatory to the Council of Europe Convention on Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings (ECAT) and European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)”.

As I write this post, we are yet to see the written decision by the Court of Appeal dismissing the Home Secretary’s appeal in that case, but I watched the hearing and the court did point out several times that since the guidance had now been changed, the specific issue in this case which led to the grant of interim relief would not arise in cases where decisions were made under the new version of the guidance.

What is the position now for trafficking claims and the UK-France agreement?

For decisions made since the change in guidance, the position is that the guidance excludes those facing removal to France from the reconsideration process. So the process for this group of people who are victims of trafficking is that they will arrive in the UK from across the Channel, be funnelled through a screening process while they are fresh from the trauma of the journey. During that interview they will be expected to provide answers that will address some fairly complex legal concepts without legal advice, to the satisfaction of a Home Office official who has every incentive to overlook any trafficking indicators so as to ensure as many people as possible are eligible to be sent to France.

The person will be moved directly into immigration detention and then be issued with a notice of intent (in English). They may or may not understand the significance of this, but it is very unlikely that they will be able to access quality legal advice. If they do, then the lawyer may identify that the person has potentially been trafficked, and ask the Home Office in its role as First Responder to refer the person into the National Referral Mechanism.

Otherwise, the person may be issued with removal directions, for a flight that could be as soon as a week away. Now the case is more urgent, they are more likely to be able to find a lawyer, so again at this stage the trafficking indicators might be identified properly, making up for the Home Office’s initial failure to do so.

Now we are at the stage where the Home Office has been forced to consider the trafficking claim. The decision maker will be aware that if a positive reasonable grounds decision is made, that will act as a barrier to removal. They will also be aware that if they make a negative decision, the person will no longer have the option of reconsideration (including the ability to obtain and submit proper evidence) if they are sent to France.

The system has therefore created a fairly sizeable incentive for the Home Office, which was already making a high number of incorrect decisions, to refuse cases at reasonable grounds stage, in the knowledge that it has just been made a lot more difficult to challenge wrong decisions.

Conclusion

The system is not being abused. Instead, it is very heavily gamed against recognition and (very limited) protections for people who have been subject to horrific abuses. This is done through high evidential requirements, very short timescales, and making it as difficult as possible for people to access legal assistance. Change is certainly needed, but not in the way that I suspect the Home Secretary has in mind.

SHARE

One Response

This is great!