- BY ILPA

Brexit briefing: free movement and the single market

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Free movement of persons and the single market

By Catherine Barnard, Trinity College, Cambridge 10 May 2016; Case studies 1, 3 and 4 provided by Laura Devine Solicitors

Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction

This note considers the centrality of migration to the EU’s single market. It also considers the relevant EU Treaty provisions and the rights they confer on both individuals wishing to work in another Member State and companies wishing to establish themselves or provide services in another Member State. It concludes with an examination of the alternatives available to the UK in the event of Brexit.

Context of free movement

Immigration has been the most sensitive issue in the period leading up to the referendum. The Leave campaign argues that ‘Brexit is the only way we can control immigration’. The Remain camp argues that:

‘The free movement of people helps Britons study, work and retire to Europe. A total of 2.2 million [the figure is now updated to 1.2 million (although this probably misses some unregistered emigrant Britons)] Britons live in other EU countries—almost as many as the number of EU citizens living here.’

What is clear from ONS data is that last year approximately 257,000 EU nationals came to the UK under EU law rules on free movement but 273,000 came to the UK from the rest of the world under UK domestic immigration rules (net migration of EU citizens was estimated to be 172,000 up from 158,000 in the year ending September 2014; non-EU net migration was 191,000, similar to the previous year (188,000)). In other words, even where the UK does have control there is more non-EU immigration than EU immigration.

Table 1 – Top 6 recent countries of origin for EU migrants, 2011-2015

| 2011 | 2015 | Change | |

| Poland | 615,000 | 818,000 | 203,000 |

| Romania | 87,000 | 223,000 | 136,000 |

| Spain | 63,000 | 137,000 | 74,000 |

| Italy | 126,000 | 176,000 | 50,000 |

| Hungary | 50,000 | 96,000 | 46,000 |

| Portugal | 96,000 | 140,000 | 44,000 |

| All EEA | 2,580,000 | 3,277,000 | 696,000 |

| Top 6 recent EEA sending countries | 1,037,000 | 1,590,000 | 553,000 |

| % of top 6 recent EEA in all EEA | 40% | 49% | 79% |

Source: Migration Observatory analysis of LFS data, quarterly averages, all ages.

The four freedoms

The EU rules on free movement of persons form one pillar of the so-called ‘four freedoms’ (the free movement of goods, services and capital being the other three). Together these four freedoms make up the ‘single’ or ‘common’ market. According to Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), the free movement of persons is now considered the core of the EU’s area of freedom, security and justice: the EU offers its citizens an area in which free movement of persons is ensured (the ‘freedom component’) but ‘in conjunction with appropriate measures with respect to external border controls, asylum, immigration and the prevention and combating of crime’ (the ‘security component’).

The founders of the EU believed there were large economic benefits of free movement of workers, namely allowing the allocation of labour to its most efficient use (ie labour should move from areas of high unemployment to low). However, as Portes points out, in fact, economic theory is ambiguous on whether factor mobility (in this context, the free movement of labour and capital) is a complement or a substitute to free trade (the free movement of goods and services). He continues:

‘In a standard Heckscher-Ohlin model, they are pure substitutes. Either free trade or factor mobility will increase the efficiency of resource allocation and will maximise overall welfare; it is not necessary to have both[…] However, the general consensus among economists is that labour mobility, like trade, is welfare-enhancing, although there may be significant distributional effects.’

The advent of the single currency may have changed this situation. According to Mundell, in the absence of the ability by states to use their exchange rate as an adjustment mechanism, an optimal currency area needs other adjustment mechanisms, in particular labour mobility. Thus free movement of persons is no longer just politically desirable but it is also economically essential for the operation of the single currency. Free movement is a safety valve.

Rules on free movement

The relevant Treaty provisions

As we have seen, the right for people to move freely from one state to another is a distinguishing feature of a common market. Yet although Article 3(c) of the Treaty Establishing the European Economic Community (now repealed) provided that the Community (as it then was) aspired to the ‘abolition of obstacles to freedom of movement for…persons’, the reality is rather different. In order to qualify for free movement, the individual or company has to be both:

- a national of a Member State (with nationality being a matter for national—not Union—law), and

- be engaged in an economic activity as:

- a worker (see now Articles 45–8 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU))

- a self-employed person/company/branch or agency (see now Articles 49–55 TFEU), or

- as a provider or receiver of services (see now Articles 56–62 TFEU).

Those falling within the scope of these ‘fundamental’ freedoms enjoy the right to free movement subject to derogations on the grounds of public policy, public security, and public health, as well as a more tailored exception for employment in the public service. These rights also apply to nationals of the EEA states (Norway, Liechtenstein, and Iceland). This is considered further below.

While the main thrust of this note will cover the free movement of economically active ‘natural’ persons (ie individuals), it should be emphasised that EU law allows companies established in one Member State to set up branches, agencies or subsidiaries in other Member States. Not only has this right benefitted ‘EU’ companies but it has also benefitted companies from non-EU Member States, wishing to gain a foothold in the single market. So a US corporation might establish a company in London and then, relying on EU law, set up branches, agencies or subsidiaries in other Member States (see case study 1).

A company which provides asset management, investment planning and fund management services throughout the US is currently looking to open an office in the UK to be able to access the rest of Europe. The main purpose of opening the UK office is to enable broader distribution of investment funds in Europe.

Citizenship of the Union

Since the Maastricht Treaty, all nationals of an EU Member State have also become ‘Citizens of the Union’ under Article 20 TFEU with rights to move and reside freely in the EU subject to the limits laid down by EU law. For those who are not economically active, these new rights appeared to offer them greater protection under EU law than they had enjoyed previously, although recent case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has cast doubt on this. For those who are economically active, the citizenship provisions have not added much to their EU rights.

For citizens moving to another Member State their rights are more fully articulated by the Citizens’ Directive 2004/38/EC and, for workers, Regulation (EU) 492/11 and the Enforcement Directive 2014/54/EC. Coordination of social security arrangements is covered by Regulation (EC) 883/2004.

UK’s ‘New Settlement’ deal

The importance of free movement of persons, as a key element in the single market package, was recently reasserted by the UK’s New Settlement deal negotiated in Brussels on 18-19 February 2016. This deal was sufficient to enable the Prime Minster, David Cameron to say he would campaign to stay in the EU. The New Settlement deal did contain a reassertion of the importance of the four freedoms:

‘The establishment of an internal market in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is ensured is an essential objective of the EU.’

The key rights

The Treaty and secondary legislation contains four main rights for EU migrants, which we shall briefly examine.

The right to leave, to enter and to reside

The Treaty and the secondary legislation allow all EU nationals (and their family members—see below) to leave one Member State, enter another and reside there. These rights are not conditional on EU nationals having a visa; they only need to have travel documents (passport or identity card).

The majority of the Member States of the EU are members of the Schengen area, which is a borderless travel zone. So a migrant worker going from Belgium to the Netherlands, perhaps on a daily basis as a so-called ‘frontier worker’, does not need to show any travel documents. However, due to an opt-out, the UK retains its borders and the right to check the travel documents of everyone who crosses its frontiers. The Schengen Agreement was initially a separate, intergovernmental agreement, but the Amsterdam Treaty incorporated the Schengen ‘acquis’ (ie legislation) into EU law.

The right to work

The Treaty and the Citizens’ Directive both give EU nationals the right to work as a worker (dependent on the employer), a self-employed person (independent of the hirer) or as a provider of services. The large majority of those who have come to the UK in recent years have come as migrant workers. Best guesses suggest there are about 3 million EU nationals living in the UK (see Table 1), but this may be an underestimate. Over the past 4 years, more than 2 million EU nationals have registered for UK National Insurance numbers which are required for (legal) access to employment. Evidence suggests that the principal driver for migration is work, although many in the Leave campaign dispute this.

Many EU migrants come to the UK to do low skilled jobs, working in the fields picking daffodils, cabbages and the like, and these are the workers who most often feature in the public’s mind. Yet many employers say their business could not function without them (see Case study 2).

A medium-sized agricultural business in East Anglia, principally farms cabbages and sends them for processing, mostly for coleslaw. The farm manager said the business needs around £1.5m of labour annually, and ‘it all comes from the continent’. Most of the farm’s permanent staff are Polish. It is far from obvious to the farm owner how he could find a workforce without bringing in overseas workers.

However, it is not just in agriculture that EU migrant workers are working. The food processing, catering and hospitality sectors are highly dependent on migrant labour.

There are EU migrant workers at all skill levels in the UK. Less discussed, but still of considerable importance, has been migration by high skilled EU workers to the UK (see Case study 3). The same basic rules apply whatever the skill level of the individual.

A sovereign wealth fund with offices and significant investments around the world, set up an office in London to provide advice and support on investments in Europe, including in the technology industry. The London office strengthens collaborations with European countries and increases the fund’s exposure in developed countries.

The London office is headed by the Executive Director who is an EEA national with a right to reside and work in the UK under European free movement law.

Not only does EU law allow for free movement of workers but it also permits EEA companies to bring their third country national (TCN) workers to work in the UK temporarily as, for example, builders on a UK construction site. This is sometimes referred to as the Van der Elst situation, following a decision of the CJEU interpreting Article 56 TFEU. The rights of these so-called ‘posted’ workers are covered by the Posted Workers Directive 96/71/EC. In fact, in the UK, there are relatively few posted workers working here under EU law.

The right to bring family members

One of the most important rights laid down by the Citizens’ Directive is for EU nationals who move to other Member States to bring their family members with them, irrespective of the nationality of those family members. Those family members also have the right to work. This has proved an important way for bringing talent to the UK (see Case study 4).

A successful technology start-up in London required a Chief Technology Officer to assist with its growth. The company was unable to identify a British national or settled worker in the UK but found a highly skilled US national to take up the position, which had a basic salary in the order of £99,500. This individual was able to join as Chief Technology Officer without delay owing to his right to work in the UK as the spouse of an EEA national.

The right to equal treatment

Underpinning Articles 45, 49, and 56 TFEU is the principle of non-discrimination on the ground of nationality (or seat, in the case of corporations). Thus, migrants and their family members must enjoy the same treatment as nationals in a comparable situation. This covers matters as diverse as terms and conditions of employment, and social and tax advantages. The principle of equal treatment means that, as the law now stands, migrant workers cannot be denied in-work benefits: they must enjoy them on the same terms as nationals.

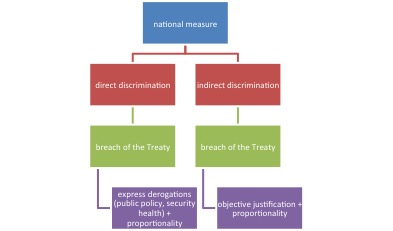

However, the principle of equal treatment is not as straightforward as first appears. It outlaws both direct and indirect discrimination (see Fig 1).

Direct discrimination involves overt, less favourable treatment on the grounds of nationality. It is unlawful unless it can be justified on the grounds of public policy, security and health. Usually Member States fail to make out this defence. This issue arose in respect of UEFA and FIFA’s rules requiring football clubs like Manchester United to limit the number of foreign players being fielded in a particular match. Since the rules were directly discriminatory and could not be saved for reasons of public policy, they were contrary to Article 45 TFEU and have since been abolished.

Indirect discrimination is the situation where a rule says nothing about nationality on its face but in fact disadvantages migrant workers. A good example is a requirement to have been resident in the host state for a period of time prior to the right to receive a particular benefit. Such rules are unlawful under EU law (because it is harder for an EU migrant to satisfy the requirement than for nationals) unless the requirement can be objectively justified and the steps taken are proportionate. This means that a state is able to defend its rules by pointing to a good reason connected with the public interest justifying its rule. So, in the case law the CJEU has accepted that states can impose a residence requirement before a migrant is entitled to receive certain benefits. This requirement is justified on the grounds that the individual must establish a ‘genuine link’ with the territory of the host state. However, the residence requirement must be proportionate—one year probably would be; five years would not.

More recent case law has shifted the emphasis away from discrimination and towards market access. So the CJEU has said that a non-discriminatory restriction on free movement which hinders free movement will be caught by the Treaty unless the rule can be objectively justified. So in the well-known football case, Bosman, the requirement that the buying club pay the selling club a transfer fee for an out of contract player, while non-discriminatory (the same rule applied whether the buying club was in same state as the selling club or a different state), restricted free movement and could not be justified. The rules have now been abolished.

The impact of Brexit

If the UK votes to leave the EU on 23 June 2016, the Prime Minster will start the Article 50 TEU process which means that he will notify the European Council. Article 50 then provides that:

‘In the light of the guidelines provided by the European Council, the Union shall negotiate and conclude an agreement with that State, setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal, taking account of the framework for its future relationship with the Union.’

Thus, while there is no obligation on the EU to negotiate alternatives to full membership, it is likely that the UK will ask for alternatives to be considered.

One possibility would be for the UK to become a member of the European Free Trade Agreement (EFTA) and then join the European Economic Area (EEA). The European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement enables three of the four EFTA Member States (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway) to participate in the EU’s Internal Market. If this option is adopted, the current rules, as outlined above, would continue to apply. The UK would not, however, have any formal input into the drafting and adoption of future EU legislation to which the UK would continue to be bound.

A second possibility would be for the UK to join EFTA and then have a series of bilateral agreements with the EU, as do the Swiss. Switzerland has over 120 separate bilateral agreements with the EU (but crucially not in the field of financial services). Under this approach, the UK would not have full access to the single market because access would depend on the existence of an agreement. It would still have to make contributions to the EU’s budget and, in return for access to the single market, it would still have to comply with single market rules.

A permutation of the Swiss model would be for the UK to enter into its own UK-EU free trade agreement involving one single agreement in return for which the EU is likely to demand that the UK accept the principle of free movement of persons. This would provide greater continuity over access to the single market, but, as with the Norwegian/Swiss options, the UK would not have influence over the drafting of EU legislation to which it would be bound. Norway and Switzerland both have higher immigration per head of population from the EU than the UK, as of 2013.

A third possibility would be for the UK to enter into a customs union with the EU, such as that which exists between Turkey and the EU, which covers trade in industrial products and some agricultural products. This does not, however, apply to persons. So in this scenario, as in the scenario in which no agreement is reached regulating the UK’s future relationship with the EU, the UK would be reliant on the protection provided by the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The WTO does have a General Agreement on Trade in Services but not on other aspects of free movement of persons. In these situations UK immigration law alone would apply.