- BY Larry Lock

Book review: Border Nation by Leah Cowan

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The now notorious conclusions of the Sewell Report on race relations in the UK are no doubt at odds with the experiences of many in this country, in particular migrant communities. Surprisingly, however, the report didn’t comment on Britain’s immigration system at all.

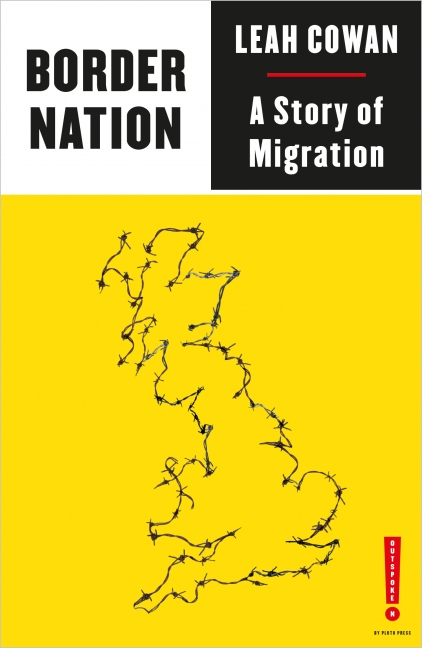

Leah Cowan’s Border Nation (Pluto Press) is a powerful and politically charged account of the racism of the immigration system, which stands as an alternative depiction of racism in Britain to the Sewell whitewash. Border Nation canvasses the ways in which geographic and invisible borders are enforced – by legislation, education, and the media – and examines how racism is a crucial tool for maintaining borders and the hostile environment in the UK.

Invisible borders

Most readers of this blog will generally cross borders with relatively minor interference from the state. Having a passport allows us this privilege. But this account of borders, Cowan argues, doesn’t paint the true picture of how borders operate. If anything, by being a passport holder we are unable to see the real picture. For many who cross them, who have little or no choice but to cross, borders are violent and dangerous places.

In Cowan’s view, the traditional “passported” account of borders also doesn’t help us to understand the invisible borders of the hostile environment, restricting the rights and liberties of those already inside the UK. Unseen to those free of immigration control, breaching these internal borders by participating in social acts such as driving or working can lead to detention and removal.

Hostile environment – old and new

Much is said in Cowan’s book about the insidious nature of the hostile environment. She also shows us that these measures are not a new feature of immigration enforcement. Cowan explores how African-Caribbean communities of the Windrush generation, persuaded to leave for Britain to buoy up the country’s failing economy, arrived here to find abysmal rights for Black workers and heavily restricted access to the state and healthcare. These restrictions weren’t in place for their white colleagues and counterparts, and were only beaten by powerful community-led activism, such as in the Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963.

In the digital age, borders have become increasingly pernicious and invasive. People are targeted by border enforcement in various complicated and indirect ways. One example is right to rent checks, held lawful by the Court of Appeal, which make it a criminal offence for landlords to rent a home to someone with irregular immigration status. This duty, introduced under the 2014 Immigration Act, creates a powerful incentive to discriminate against communities of colour. Over 70 years on from the docking of the Empire Windrush, little has changed for migrant communities and borders continue to proliferate.

“Dehumanising” media coverage

Outside of the legal sphere, Cowan points to the complicity of the British media in maintaining borders. Many will remember the aggressive coverage of the 2015 refugee crisis in which refugees were dehumanised as “swarms” of migrants. Cowan argues that the same dehumanising impulse can be found in coverage of the Shamima Begum case. Begum, Cowan argues, would have been recognised as a victim of grooming under English criminal law. The majority of the media ignored this, presenting her as a dangerous extremist, supporting the government’s case to strip her of her British citizenship. Just as the dehumanising coverage in 2015 led to an EU-wide crackdown on “irregular immigration”, so does the Begum case justify stripping British citizens of their citizenship — a uniquely cruel form of punishment. Dehumanising migrants and communities of colour, then, is a crucial tool for maintaining the hostile environment.

Cowan also makes the powerful point that the British media establishment is largely made up of those who do not experience the sharp edge of borders, and yet are the first to dehumanise those most vulnerable to their effects, such as asylum seekers and refugees. Again, Cowan calls this out as a kind of privileged ignorance. For those rich enough to go abroad for travel and leisure, or move somewhere for new work, borders are something we are choosing to cross. For others, there is far less choice involved in leaving your home, your language, your community behind, possibly for good. Even for those ever-demonised “economic” migrants, the decision can never be easy.

Resisting borders

Cowan ends by canvassing some of the ways in which borders have been resisted in recent years. She cites the 100 hunger strikers at Yarl’s Wood who in 2018 drew national attention to the removal centre’s conditions and the impact of indefinite immigration detention. She also points to the importance of grassroots and local activism. One example she gives is the Anti-Raids Network, whose local groups organise to disrupt and, where possible, fight off immigration raids. Resistance, Cowan says, is possible and often effective. Recent events in Glasgow bear this out.

More pragmatic (or cynical) folk may disagree with some of the methods of resistance, and possibly the notion of a borderless world. But in a sense, the solutions Cowan canvasses match the originality of those in power, who are constantly inventing new ways to make the lives of migrant communities in Britain less liveable. The government is thinking radically about this topic – why, Cowan asks, aren’t we?