- BY Colin Yeo

Bad cases make bad law: the unintended consequences of denaturalising bad guys

Table of Contents

ToggleThe power to denaturalise a British subject on the basis of their behaviour was first introduced by legislation in 1918. With some adjustments, the power remained broadly the same until as late as 2002. Essentially, only a person who had naturalised as British could be stripped of their citizenship and the main grounds for doing so involved disloyalty or disaffection to the Crown, assisting an enemy or proven criminal conduct. These powers were exercised against some German and allied nationals who had naturalised as British but fell into abeyance. The last denaturalisation under this legal regime occurred in 1973.

After 80 years of legal continuity, a period which included a second world war, the Cold War and The Troubles, amongst other external-internal existential security threats, a series of fundamental changes to the law on denaturalisation began in 2002. Why?

The evolution over the last twenty years of British law on denaturalisation — or citizenship stripping — is a case study in bad cases making bad law. The law was changed repeatedly between 2002 and 2006 specifically to enable the government to strip the citizenship of particular high profile individuals. Relatively restrained use was initially made of these new powers, with only those high profile individuals targeted for denaturalisation. A change in government in 2010 introduced changed attitudes to the value and meaning of citizenship. The new government found itself in possession of very considerable discretionary powers and set about making extensive use of them.

Abu Hamza

In 2002, reforms for the first time enabled denaturalisation of those born as British citizens, as long as they were not thus rendered stateless, and introduced a new test of doing anything ‘seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the United Kingdom’. Both of these changes represented genuinely radical changes to the law.

These reforms were presaged by a White Paper, albeit only in scant outline, and appeared in the original draft legislation that was presented to Parliament. The new test for denaturalisation was derived from international conventions on statelessness and nationality. The changes look like they were considered relatively thoroughly in advance, at least in comparison to later changes.

But just three days after the new powers came into effect, the notorious cleric Abu Hamza was served with a notice of intention to strip him of his British citizenship. He was possibly the only, if not then one of the only, British citizens targeted for denaturalisation under this new but short-lived legal regime. Were the changes actually all about getting rid of Hamza?

Hamza held Egyptian citizenship and had naturalised as British, making him a dual national. He could therefore potentially be removed to Egypt and was potentially subject to denaturalisation under the old legal regime. However, he had been convicted of no offences and disloyalty or disaffection might well have been considered too ephemeral a mental state to use as a basis for such a draconian and controversial act.

It is plausible to suggest that the 2002 reform was conceived specifically to target Hamza. He was certainly in the public eye from at least 2001 onwards. Shortly before the reform came into effect, then Home Secretary David Blunkett stated, referring specifically to Hamza, that ‘every word and every action is being monitored, and we need to do so in a way that secures the confidence of people who are sick and tired of individuals like him abusing our hospitality.’

Without doubt, the change certainly enabled his denaturalisation and it was intended for use against other perceived supporters of radical political Islam.

Abu Hamza Again

However, there is an important post script. Denaturalisation did not take immediate effect because Hamza appealed and the law provided that his status was protected until the conclusion of the appeal. While the appeal was ongoing, the Egyptian government then stripped Hamza of his Egyptian citizenship. This meant that the only nationality held by Hamza was his British citizenship. He could therefore no longer be denaturalised by the British government, because to do so would render him stateless. His appeal succeeded and Abu Hamza remains a British citizen to this day.

As Audrey Macklin has put it, there is a ‘race to see which country can strip citizenship first. To the loser goes the citizen’. The British government, eager to avoid losing any similar races in future, changed the law again in 2004.

The legal provision continuing citizenship during any appeal was quietly repealed by a new piece of legislation not otherwise addressing nationality law at all: paragraph 4 of Schedule 2 of the ill-named Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants, etc) Act 2004. A person’s citizenship would be immediately withdrawn on receipt of a decision, irrespective of whether the person pursued an appeal or not. If the appeal were to succeed, the person’s citizenship would be restored.

The change had a significant side-effect. If a British citizen was denaturalised while outside the country, this meant they would be unable to return, even to contest any appeal they might lodge. It would also become harder to resource and contest any appeal, or even to get an appeal lodged in the first place given the strict and inflexible time limits imposed. In a process led by the security services, denaturalisation decisions were henceforth served as soon as a person was outside the country, in effect exiling the recipients.

However, the old law would continue to apply to past events and actions; it was only matters arising after the commencement of the new test to which the new test would apply. This was to become relevant to the next ‘bad guy’.

David Hicks

Further legal changes were wrought to the law of denaturalisation in 2006. The ‘seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the United Kingdom’ test was replaced with one of merely whether denaturalisation was considered by the Home Secretary to be ‘conducive to the public good’.

The new test was on the face of it unrelated to issues of state-level or civic harm or questions of loyalty. The threshold of conduct was potentially far lower and it was far harder to challenge in court. Indeed, the new test for denaturalisation used identical wording to the test for deporting foreign nationals on the basis of criminal or merely undesirable behaviour. It is an incredibly low bar for taking away a person’s citizenship.

Unlike the reforms of 2002 and 2004, though, this change was not seemingly one that was pre-planned. There was no White Paper and the original Bill presented to Parliament on 22 June 2005 was silent on the issue of citizenship deprivation. The relevant clause was only introduced by the government at the scrutiny stage of the legislative process, in October 2005.

The minister responsible, Tony McNulty, claimed that the purpose was to enable denaturalisation in the event that British citizen engaged in ‘certain unacceptable behaviours’ in breach of the government’s ‘wider counter-terrorism initiative’. Admitting that the existing powers introduced in 2002 had not led to any actual denaturalisations (although notably silent on the failed attempt to denaturalise Abu Hamza), McNulty justified the change by asserting ‘[w]e think that things have moved on and it is appropriate to have the power that we are discussing in the locker, if nothing else, given the way circumstances are.’

Pausing here, that was a truly remarkable thing to say.

Past behaviour by a British citizen would not be the only factor in denaturalisation decisions under the new test. Ministers would also consider ‘potential threat’ and ‘a particular threat now from which the public need protection’. Finally, the minister all but admitted that the changes were not compatible with the international treaties from which the ‘seriously prejudicial’ test had been drawn.

A seemingly unrelated amendment was introduced at the same time, which imposed for the first time the good character test on registrations as British nationals.

The saga of eligibility for British citizenship of David Hicks was running in parallel with these developments. Hicks was an Australian citizen who had ended up detained by the United States government at Guantanamo Bay on suspicion of involvement with Islamist terrorist groups prior to his capture in Afghanistan in 2001. He reportedly became aware he was eligible for registration as a British citizen in September 2005 and submitted an application soon afterwards in the hope this might prompt his release from detention.

The application was rejected by the Home Office in November 2005. Eventually, after a series of court defeats for the British government, Hicks was briefly to be registered as British. Because the ‘seriously prejudicial’ test only applied to events after it came into force in 2003, it was actually the original test for citizenship deprivation set out in the 1981 legislation that was considered by the courts in Hicks’ case. The Court of Appeal held that Hicks could have shown neither disloyalty nor disaffection because both require ‘an attitude of mind towards an entity to which allegiance is owed, or at least to which the person belongs or is attached.’ He had not been British at the time so had owed no allegiance.

In the meantime, the British government introduced the two amendments discussed above to the Bill then passing through Parliament. These amendments would have empowered the government to refuse Hicks’ registration on good character grounds and, because this came too late, also enabled the government to denaturalise Hicks as soon as his registration had eventually been granted in July 2006.

Two major changes to British nationality law were seemingly driven by one man. The lowering of the bar for citizenship stripping would affect hundreds of British citizens. The imposition of a good character test for registrations would go on to affect thousands.

Al Jedda

The correlation between legal change and individual cases does not end there. In 2014, the law was changed so that a British citizen could be in some circumstances be denaturalised even if this rendered them stateless.

Once again, the relevant clause was not included in the Bill originally presented to Parliament. It was only after the handing down of the Supreme Court decision in Al Jedda v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2013] UKSC 62 that the Bill was amended to include this provision. The accompanying explanatory notes accompanying the amendment made the link absolutely explicit, specifically citing the Al Jedda case. The government minister presenting the amendment in the House of Lords was more circumspect, arguing the new power was needed ‘to allow a small number of naturalised citizens who have taken up arms against British forces overseas or acted in some other manner seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the UK to be deprived of their citizenship, regardless of whether it leaves them stateless.’

D4

The pattern was repeated in the parliamentary session of 2021-22. The Nationality and Borders Bill initially introduced to Parliament on 6 July 2021 did not touch on denaturalisation. On 30 July 2021, the High Court held that notice had to be given in writing in order for a denaturalisation decision to take effect in a case called R (On the Application Of D4) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2021] EWHC 2179 (Admin) (later confirmed by the Court of Appeal).

It did not take the government long to respond. An amendment was introduced at the committee stage in November 2021 to abolish this requirement.

Unintended consequences

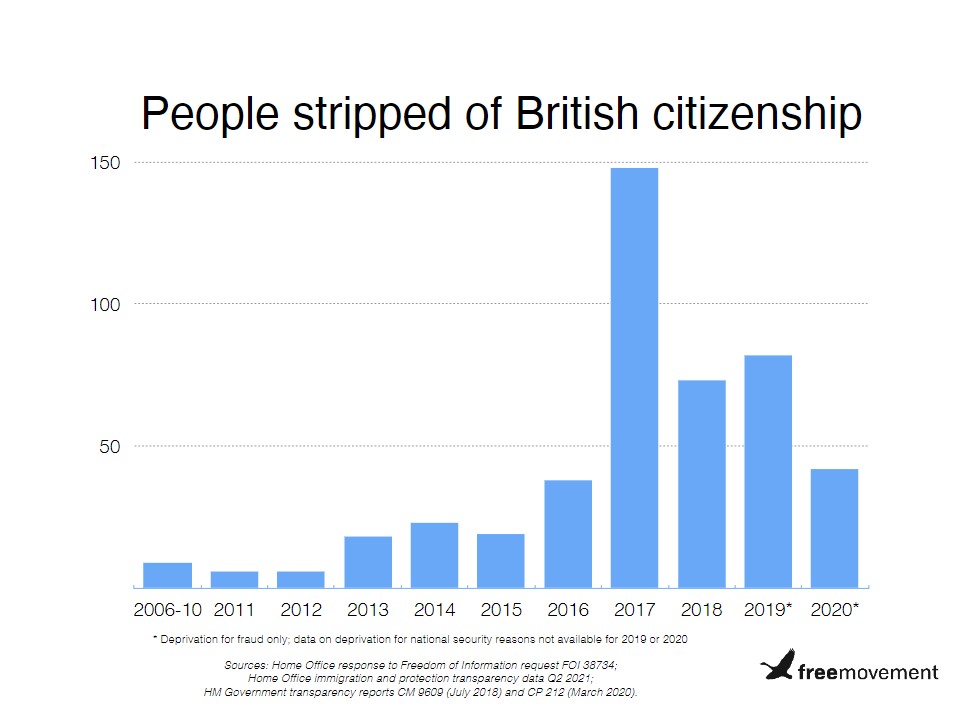

The governments and ministers that introduced the initial changes to the law between 2002 and 2006 were relatively restrained in making use of them. The numbers of denaturalisations remained very low until 2010, when there was a change of government and a change of approach. For the incoming government, citizenship was a privilege not a right.

The problem is that when very low legal thresholds for draconian actions are introduced, ministers and civil servants are handed huge freedom of action. Particularly in the field of immigration and asylum law, they are subject to huge political and media pressures. It should be no surprise if they are inconsistent in their use of the very considerable powers with which they have been entrusted by an earlier parliament. It should also be no surprise that unconscious bias asserts itself in these circumstances.

Behaviour-base denaturalisations peaked in 2017 at around the time that the territorial area in Iraq and Syria controlled by the ISIS or Islamic State group was collapsing. British citizens who had associated with the group were looking to escape and return home. The Home Secretary at the time was Amber Rudd, but it is her successor, Sajid Javid, who has provided the most detailed public justification for denaturalisation action.

Speaking on breakfast television about Shamima Begum in 2021, several years after his time as Home Secretary, he claimed that ‘[i]f you did know what I knew, as I say because you are sensible, responsible people, you would have made exactly the same decision, of that I have no doubt.’ Javid retrospectively framed the decision as one involving risk to the British public, essentially.

He has also, however, stated a very different justification for denaturalisation. At a party conference speech in 2018, when he was still Home Secretary, he boasted of expanding use of citizenship deprivation powers to ‘those who are convicted of the most grave criminal offences. This applies to some of the despicable men involved in gang-based child sexual exploitation.’ There is a clear moral dimension to this statement.

A few months later, also in 2018, he discussed the denaturalisation of a group of dual national Pakistani-British men convicted of sexual offences. Pressed on the risk to citizens of Pakistan once they were removed there, Javid he reverted to suggesting it was all a matter of risk, albeit only of risk to the British public: ‘[m]y job is to protect the British public and to do what I think is right to protect the British public.’

More recently, lawyers have reported that denaturalisation action is now being pursued against individuals convicted of human trafficking offences. It is hard to see how removing a person to a country from which they have previously trafficked others reduces risk to either the citizens of that country or the United Kingdom.

The expansion in the use of denaturalisation powers from threats to national security to very serious crimes would have been impossible without the reforms to citizenship deprivation law enacted in 2006 in response to the case of David Hicks. It is not realistically possible to argue that serious sexual offences or human trafficking amount to acts seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the United Kingdom. It clearly is possible successfully to argue that such conduct is sufficient for the Home Secretary to be satisfied that denaturalisation is conducive to the public good. After all, the Rochdale sex offenders lost their legal challenge: Aziz & Ors v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2018] EWCA Civ 1884.

The fact that every known case of behaviour-based denaturalisation involves a Muslim has not gone without comment. There has undoubtedly been a serious threat to public safety from some individuals who are Muslim but it would be entirely unrealistic to suggest that the threat is uniquely posed by Muslims. Denaturalisation has never been pursued against Irish nationalists, adherents of right-wing terror groups, anarchists or other dual foreign nationals representing a threat to national security. It is possible that no such individuals were identified who held dual citizenship and were thus eligible for denaturalisation but this seems inherently unlikely.

The discrimination becomes even more stark when the case of the Rochdale sex offenders is considered. The men who were denaturalised were all Muslim men of Pakistani origin. It seems highly likely there have been many, many other dual nationals who committed sexual and other offences of similar or worse gravity — where seriousness is measured by the length of sentence rather than media judgment — who were never considered for denaturalisation.

The changes made to denaturalisation powers in the 2000s were naive. The government of the day may have intended only judicious, sparing use of citizenship stripping. If so, the scope of those intentions were not reflected in the very wide powers the government conferred on itself and, importantly, on its successors. Subsequent governments have made ever more extensive use of the powers that were conferred on the Home Secretary.

In the process, two tiers of British citizenship have emerged. Those with no foreign parentage are relatively secure in their status because they would be rendered stateless if they lost their British citizenship, meaning the power cannot be exercised against them. But for those who have naturalised or have foreign parentage, British citizenship is now little more than a readily revocable form of immigration status.

I’m grateful to Fahad Ansari for making the time for an interesting discussion of these issues.

SHARE