- BY Colin Yeo

What is actually going on at the Home Office? A guide for journalists

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

We’ve seen a constant drip of leaks about the UK’s “broken” asylum system and how the upcoming Borders Bill or Sovereign Borders Bill or New Plan For Immigration or whatever it’s called will be the “biggest overhaul of the asylum system in a generation”. A lot of this is cover for problems that the current management of the Home Office has caused. We thought (for which read hoped) it would be useful to put together some objective information from the government’s own statistics about what is really going on so that journalists and others can put the current state of affairs in context.

Priti Patel and other senior government ministers might even find this helpful. We’re never quite sure what senior civil servants are telling them and whether those civil servants are entirely straightforward about what is really going on in their department and why.

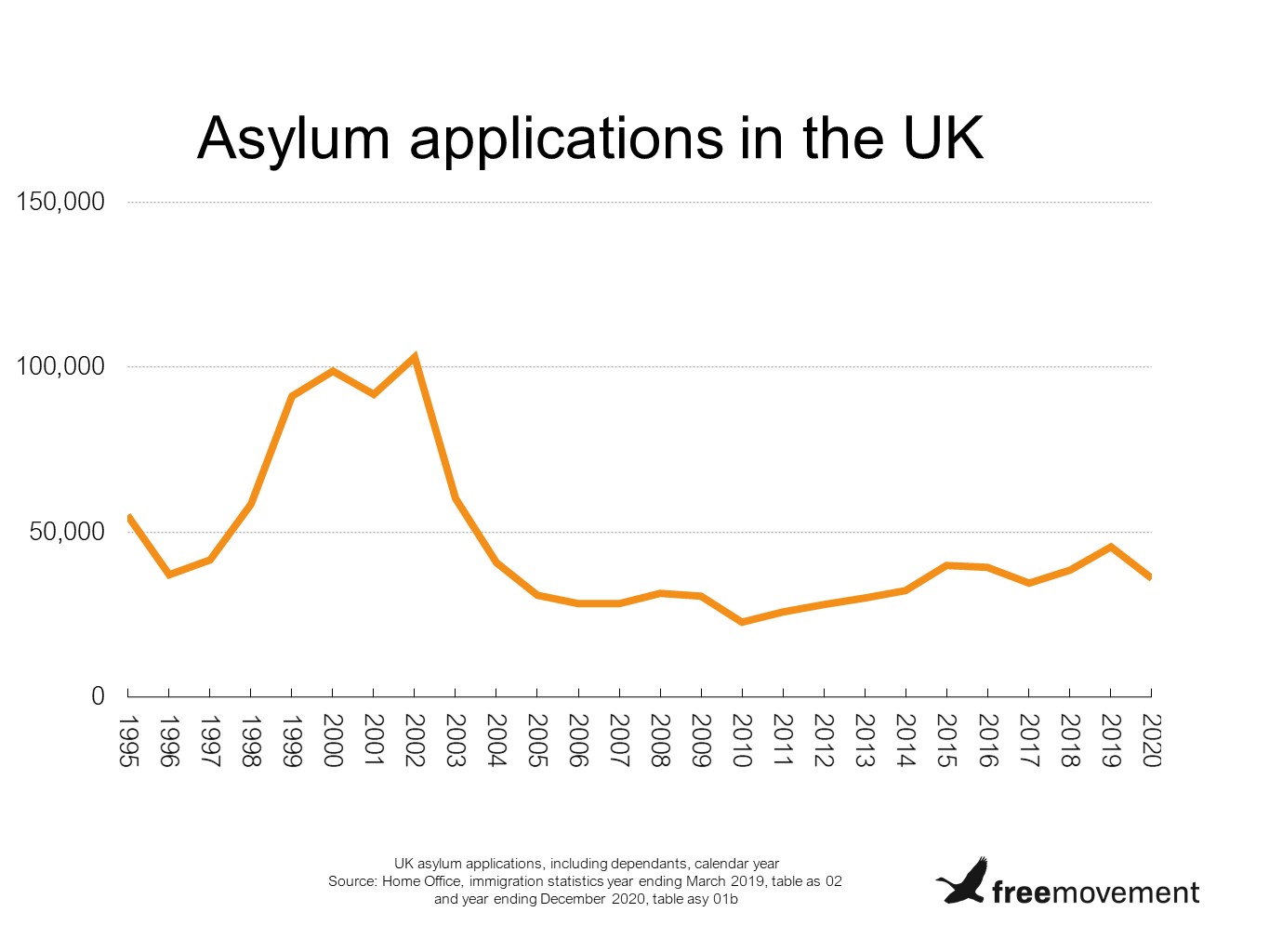

Asylum numbers are historically low and falling, not rising

The number of people claiming asylum in the UK is low compared to the peak at the turn of the century. In 2019, around 46,000 people did so — around half the annual number in the early 2000s.

Asylum applications then fell 20% last year, to 36,000. This was despite an increase in the number of people crossing the English Channel in small boats, who as the House of Commons Library points out only “partly offset” the decrease in the number of people arriving at ports and airports. You cannot claim asylum from outside the UK, so to set foot on British soil asylum seekers have changed their route of entry, from regular commercial travel to dangerous Channel crossings. But, overall, the number of people that the Home Office needs to process fell significantly in 2020.

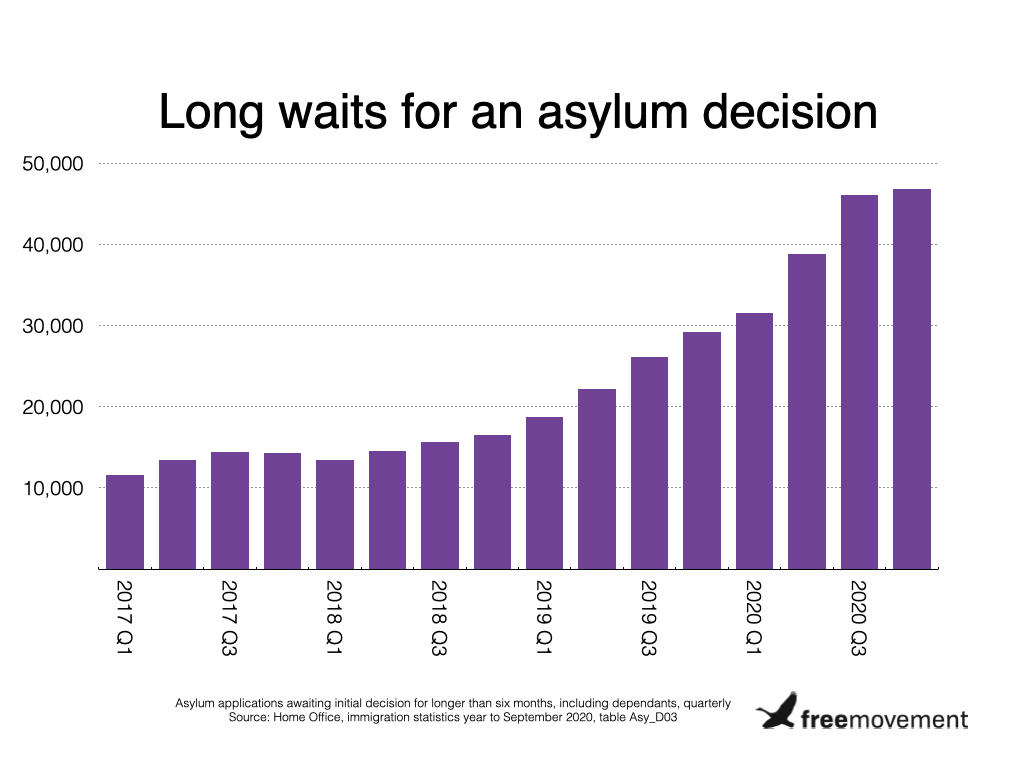

Waiting times for Home Office decisions have soared

There are major delays in the asylum system, but these have nothing to do with the appeal process or devious claimants or scheming lawyers. There are now nearly 50,000 asylum seekers who have been waiting for over six months for a decision on their asylum application, up from 11,500 only three years previously. The Home Office is simply slower to make decisions.

As further context, the mean (average) waiting time for an asylum appeal was 25 weeks (i.e. about six months) in the period January to March 2020, before the pandemic messed that up by making most hearings impractical. That was considerably quicker than hearings in the employment or social security tribunal.

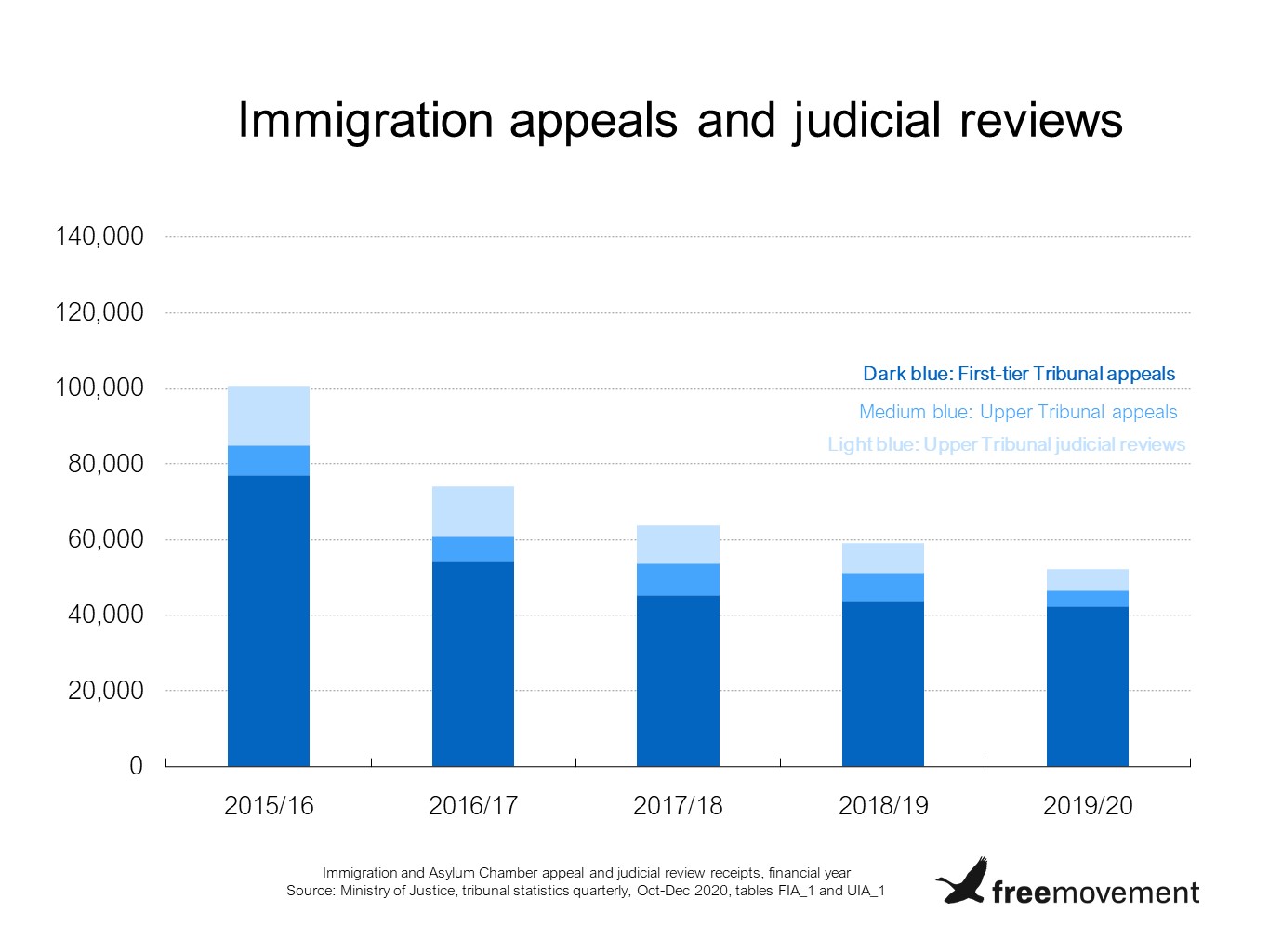

Numbers of immigration and asylum appeals are falling, not rising

The Home Office paints a picture of an immigration system bedevilled by endless appeals. In fact appeal rights have been slashed for years: the number of cases lodged with the First-tier Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) peaked at over 200,000 in 2008/09 and has fallen every year since. Appeals are now around one fifth the rate of a decade ago, at 40,000-45,000 a year.

The number of onward appeals to the Upper Tribunal have fluctuated, but last financial year saw the lowest on record, at 4,400. The average over the preceding decade was 8,000 a year.

Judicial review applications in the Upper Tribunal have also fallen sharply, from almost 15,700 five years ago to 5,700 in 2019/20.

All the above figures largely exclude the effect of the pandemic, since the 2019/20 financial year ended on 31 March 2020, just as it was getting going.

The chart below shows the number of First-tier Tribunal appeals, Upper Tribunal appeals and Upper Tribunal judicial reviews lodged over the past five years. It is perhaps not 100% statistically kosher to mash them all together like this, but for illustrative purposes it gives a clear sense of the trend even pre-pandemic.

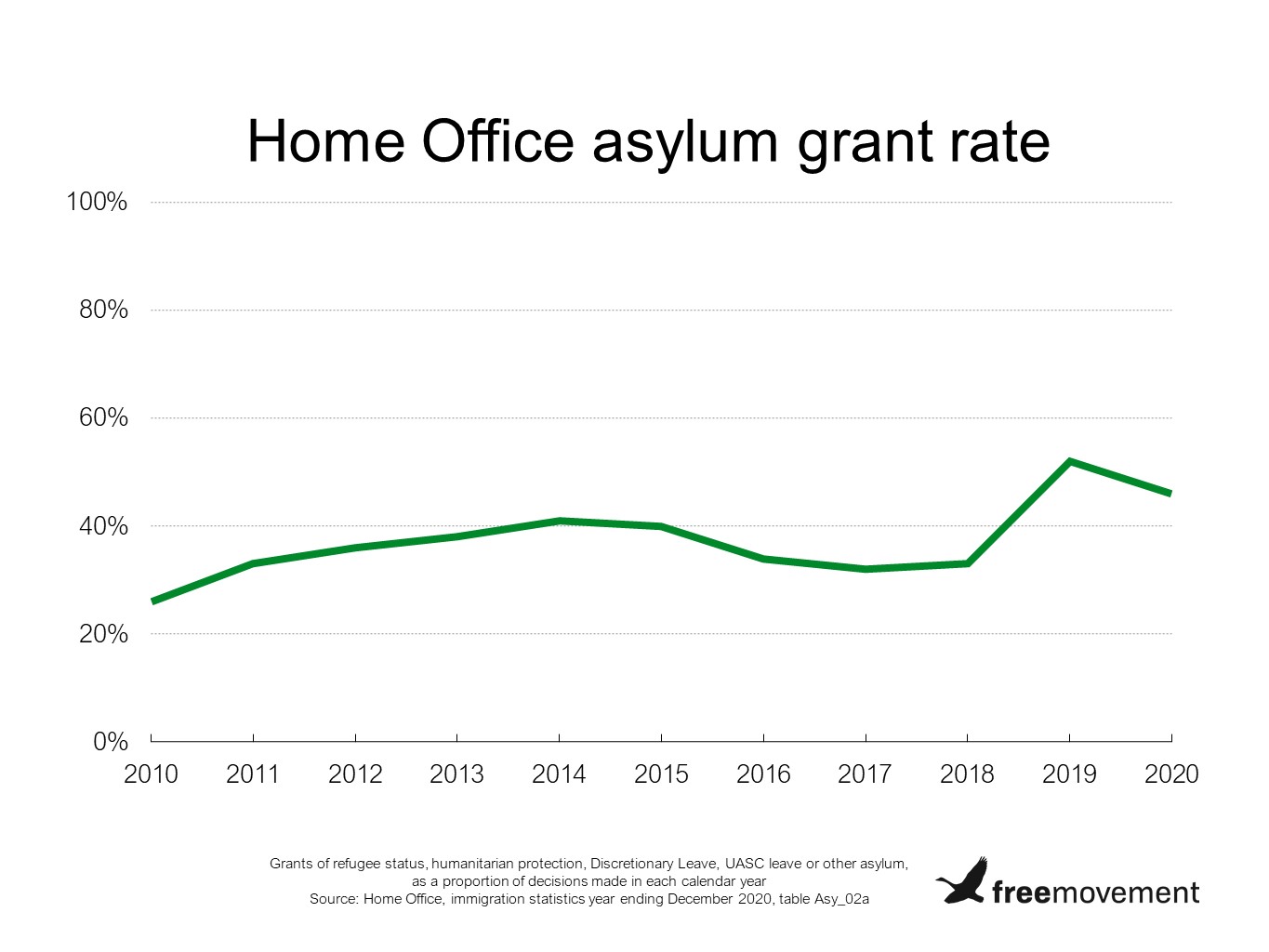

More asylum seekers are genuine refugees than ever before

Asylum seekers are among those who can lodge an appeal against a Home Office decision as above — but they do not need to do so if recognised as a refugee straight off the bat. The proportion of asylum seekers granted refugee status, or a related form of international protection, at the “initial decision” stage has been around 50% over the past couple of years. This is a significant rise: the 2010-2018 average was 35%.

The proportion of successful asylum applicants is pushed up considerably further on appeal. Home Office statisticians say that “the final grant rate typically increases by 10 to 20 percentage points” after immigration judges have had their say. So if we add 10 to 20 percentage points to the 2020 initial grant rate of 46%, that gives a projected success rate for asylum applications lodged that year of between 56% and 66%. Looking back to known rather than projected outcomes, the period 2016-2018 saw a final grant rate — initial grants plus grants following appeal — of 54%.

In other words, a clear majority of the asylum seekers that the Home Office treats so appallingly are eventually recognised as genuine refugees.

Looked at another way: of those who are refused asylum but appeal, an awful lot go on win that appeal. In 2019/20, the First-tier Tribunal success rate in asylum appeals specifically was 48%.

The statistical series does not go back into the mists of time, but a parliamentary answer reveals that the success rate in the mid 1990s, when a lot of punitive measures against asylum seekers were introduced, was just 4% on initial application (and 4% on appeal).

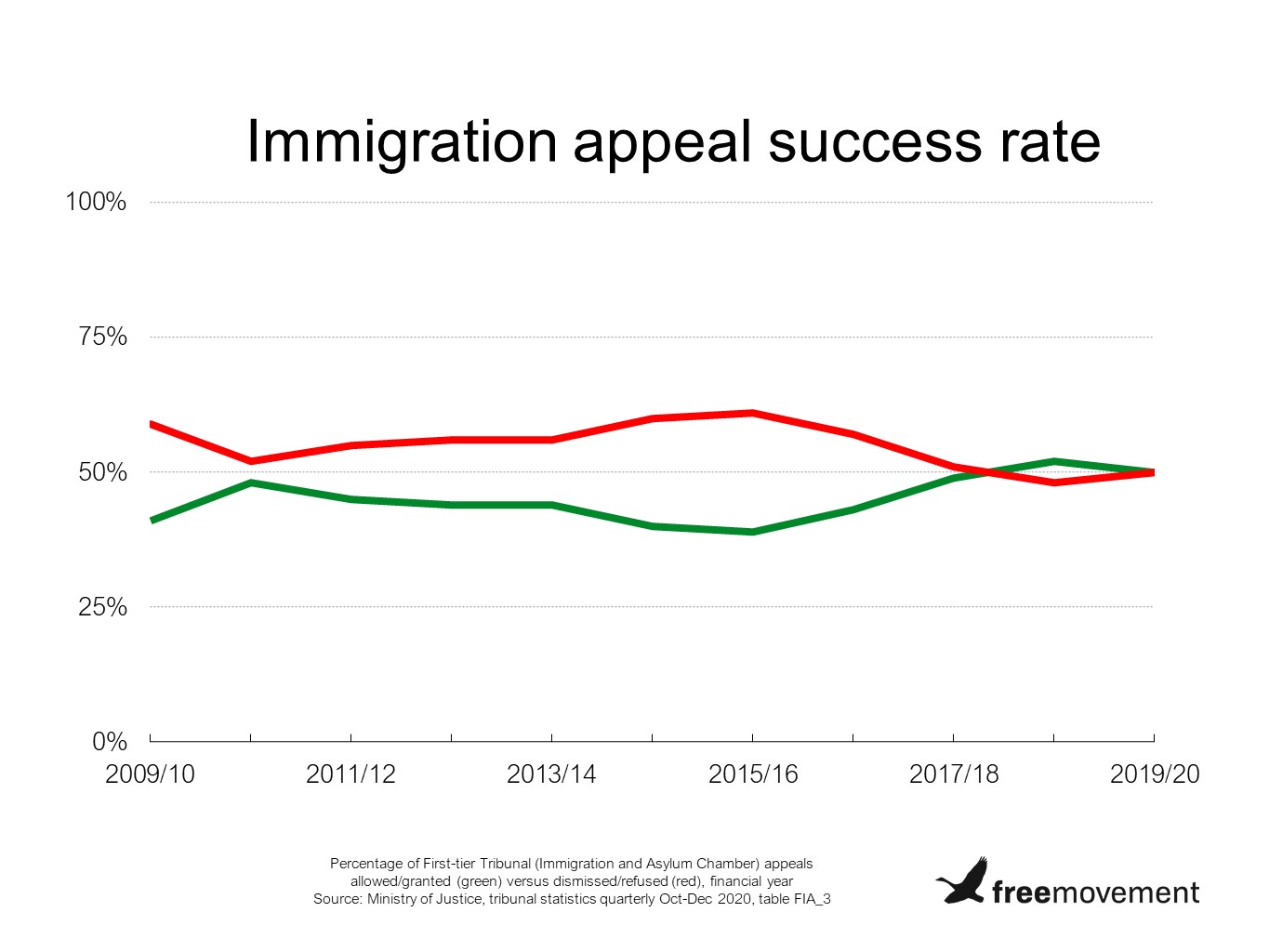

A LOT of immigration appeals succeed

Success rates in asylum appeals are actually a touch lower than for immigration appeals more generally. Of those who challenge a Home Office decision in the First-tier Tribunal — typically on whether they should be deported or removed from the UK — the success rate is basically 50/50.

We don’t have equivalent figures for the Upper Tribunal because the data for successful appeals bundles together wins for migrants with wins for the Home Office. We do have figures on judicial review outcomes, which at first glance look like a very poor rate of return: just 30 out of 7,300 immigration JR applications decided last year by the Upper Tribunal were successful. But the data does not record cases that were settled. If a judge has given permission for a judicial review to go to a full hearing, the Home Office will very often concede the substance of the case rather than risk losing in court.

Around 1,100 cases were granted permission, either on the papers or following an oral hearing, last year, on top of the 30 outright wins. So around 15%, or one in seven, Upper Tribunal judicial reviews ended up in some kind of positive outcome for the applicant.

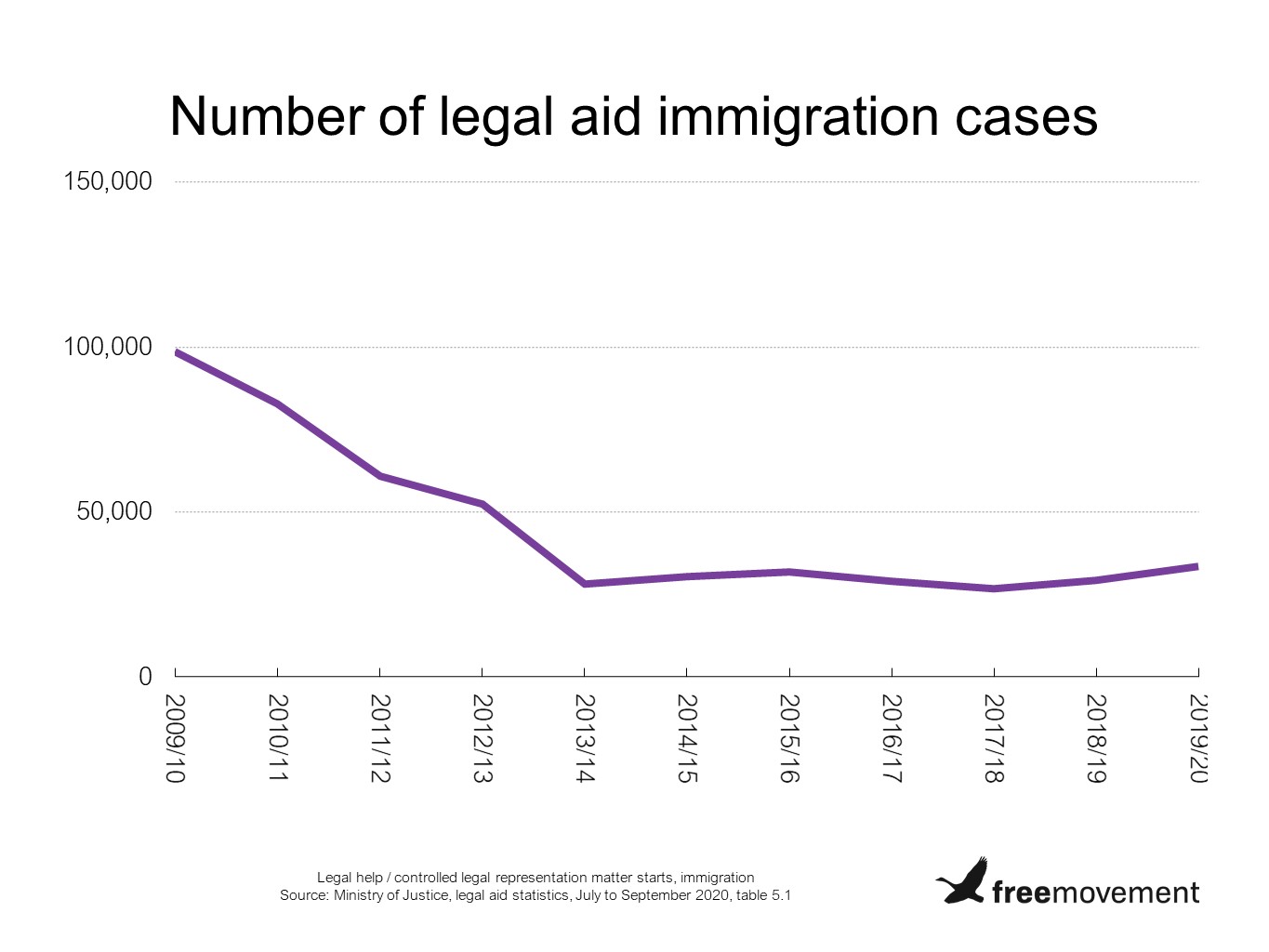

Legal aid spending is already at historically low levels

Legal aid for immigration or asylum case (in practice mainly the latter) has also been in steep decline. Government funding for legal help or representation halved in the ten years from 2009/10, from £79 million to £37 million, Ministry of Justice figures show. There was an increase in 2019/20, back up to £43 million, but this is again pre-pandemic and the provisional figures for 2020 show spending way down.

The number of cases has, naturally, followed a similar trajectory: from 99,000 “matters started” in 2009/10 to 33,000 in 2019/20 (and now heading south again).

Enforced and voluntary returns are falling, not rising

The number of people removed from the UK — i.e. deported for criminal offending, or just sent packing for lack of a visa — has gone down over the past decade. Instead of making our own charts to illustrate this we can just rely on one put together by the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford. Hover over it to get the annual figures.

As this shows, both enforced removals and voluntary departures have gone down. In the former category, the 7,400 people sent packing under the direct supervision of the Home Office in 2019 was the lowest on record. In the latter category, voluntary returns went from 27,000 to 15,000 just between 2016 and 2018.

There is no particular legal reason this should be the case. The Home Office press people have been busy cobbling together selective stats on how many people raise legal issues to delay removal, but the statisticians who put out the regular quarterly report make no mention of “last minute claims” being a factor in the decline. The fact that many people do not assert a legal barrier to removal until they are in an immigration removal centre is in any case a reflection of the lack of legal aid covered above.

It seems that the Home Office has itself put less of an emphasis on removals, whether by design (in view of the Windrush scandal) or due to its own administrative failings. It takes an especially brass neck for an institution proving unwilling or incapable of discharging its basic operational functions to declare that the only solution is sweeping legislative reform.

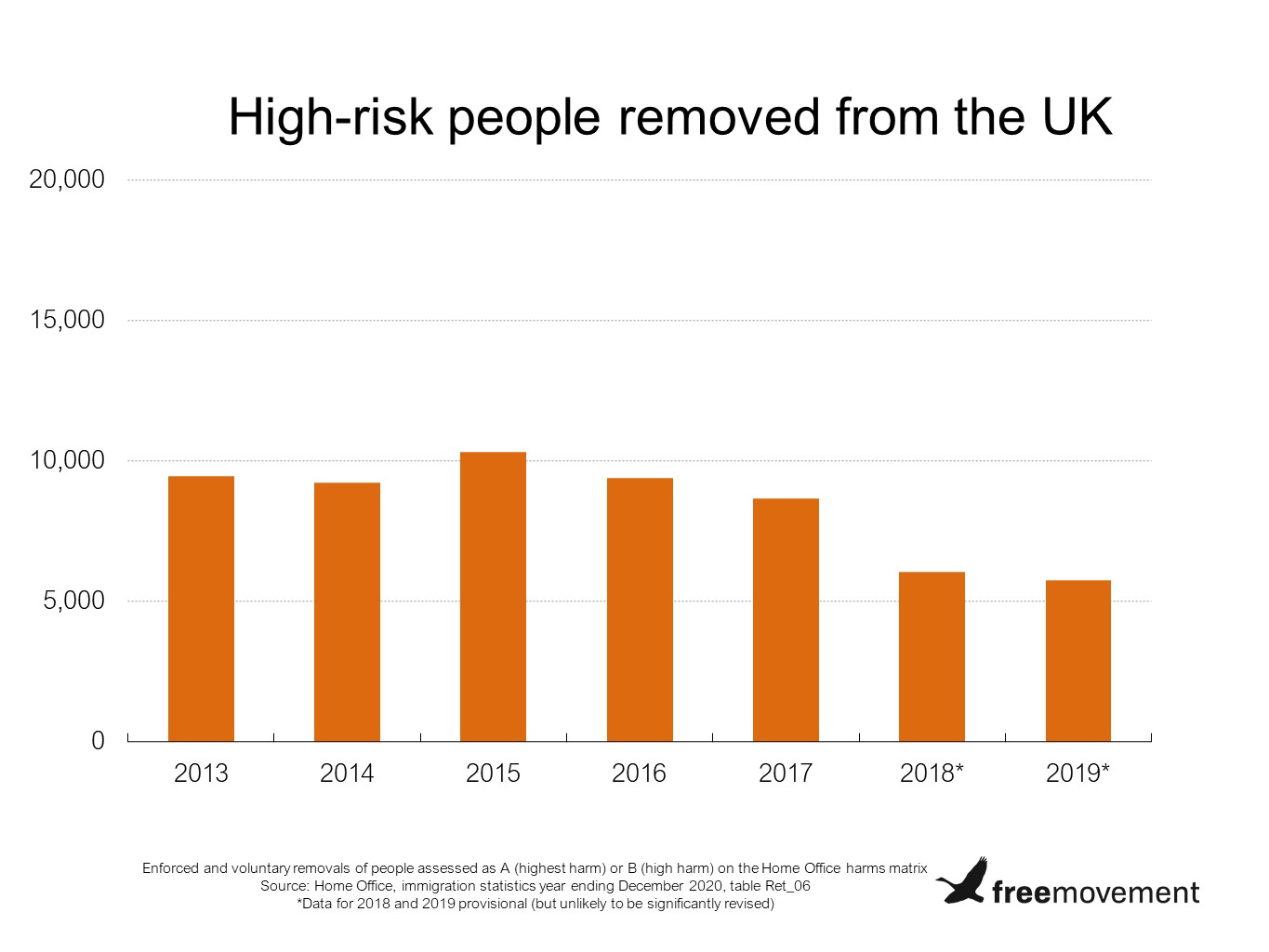

Far, far fewer serious criminals are being deported

You do not have to be a foreign national offender to be removed from the UK, but the government understandably emphasises that aspect of its removals policy and nobody ever lost votes by deporting serious criminals. If overall removals were down but criminal deportations steady or up, many people would think that a perfectly enlightened prioritisation.

That is not what is happening. Removal of foreign national offenders peaked in 2016, and has since fallen by 20%, to 5,100 in 2019. The total appears to include an unknown number of EU citizens who “abuse or did not exercise Treaty rights”, such as by sleeping rough, and may not in fact be “foreign national offenders” at all. At last count, there were over 10,000 foreign national offenders subject to deportation living in the UK, twice the number of five years earlier.

Looked at another way: the Home Office categorises removals by the degree of “harm” caused by the person concerned. The number of returns (enforced and voluntary) involving those rated as “highest” or “high” harm feel from over 10,000 in 2015 to 5,600 in 2019.

At the start of this year, the Home Office floated the idea of reducing the legal threshold for automatic deportation from 12 months to six months. This is not a move calculated to snare more hardened criminals.

Questions we’d like answered

So, why is the Home Office taking so long to make initial decisions on asylum claims? Why has the number of cases waiting more than six months for a decision quadrupled over the last four years? What has happened to staffing levels in the asylum teams? And how would improvements to the “efficiency” of the appeal process address this problem at all given the cause lies entirely within the Home Office?

Anyway, what is the point in speeding up the appeal process if the Home Office then does very little to actually remove asylum seekers? The number of enforced returns was at an historic low even before the pandemic began, and that was not because of some clever new legal wheeze. It seems to be simply because the Home Office has de-prioritised removing failed asylum seekers.

More importantly, what is Home Office doing about the next Windrush-style scandal for EU citizens who miss the EU Settlement Scheme deadline? Or doing for the children of EU citizens born in UK and entitled to British citizenship but who in future will never be able to prove it because they to do so they would need to submit five years’ worth of their parents proof of working?

There’s a lot wrong at the Home Office. Blaming genuine refugees or their lawyers does nothing to fix any of it.

Interested in what really goes on in our immigration, asylum and citizenship system? Check out Colin’s book from last year:

SHARE