- BY Colin Yeo

The Home Office must adopt a principled approach to DNA testing

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

In 1985, immigration solicitor Sheona York read an article in the Guardian about a new technology for proving someone’s identity. She called the inventor, Professor Alec Jeffreys, at the University of Leicester to see whether this “DNA testing” could help to resolve an immigration dispute. The Home Office was demanding proof that her client was a British citizen, which he could only establish if he could prove that he was indeed related to his parents and had inherited their British citizenship. Professor Jeffreys agreed — and that, as he later told the BBC, was “the very first [legal] case ever tackled by DNA anywhere on this planet”.

I was at the tribunal when the mother was told that her two-year battle to save her son [from removal] was over. The look in that woman’s eyes — pure magic.

The University of Leicester switchboard was immediately jammed with callers desperate for Professor Jeffreys’ help in their own cases. The usefulness of DNA testing in resolving wrangles over inherited British nationality has been obvious ever since.

Today, sadly, DNA testing is cynically over- and under-used by immigration officials, depending on which is most likely to lead to refusal.

Overuse of DNA testing in nationality cases

In some contexts, DNA tests have become routine. In 2015 new British Nationality (Proof of Paternity) Regulations were brought in, for example. These apply to birth certificates issued on or after 10 September 2015 where the father was not married to the mother at the time of the child’s birth.

Instead of a birth certificate naming the father automatically acting as sufficient proof of paternity, as previously, these amending regulations inserted the word “natural” before “father” and require a person claiming British citizenship to satisfy the Home Office that the claimed father is the “natural father”.

The new regulations relegate the birth certificate from definitive proof of paternity to just one relevant document, and officials have thereby been encouraged to ask for DNA evidence in more and more cases.

The guidance to officials does not demand that DNA evidence is submitted but it certainly does not discourage it:

However, we may normally accept that a man is the father of an illegitimate child if

• paternity has been acknowledged in some other official context – for example, if the child was born abroad and there is reliable evidence that the claimed relationship has been accepted for United Kingdom immigration purposes; or

• he has stated that he is the father and we have confirmation of that from the mother, provided there is no evidence to suggest that their evidence is false (e.g. given in the hope of gaining an immigration advantage)

Instead of taking a sensible and pragmatic approach, too many officials jump straight to demanding a DNA test. It is less time consuming for the official in question than trawling through assorted other documents, it matches the refusal culture of disbelief and it bears the imprimatur of reliable, objective science. The consequences to the family of being asked for a test are apparently disregarded.

The Home Office has recently admitted that it has also been demanding DNA evidence where foreign parents seek to stay in the UK on the basis of their family life with a British child — in breach of its own policy. The Project for the Registration of Children as British Citizens says that there has been a marked increase in unreasonable DNA test demands in the past few years.

DNA testing should be used with extreme caution. Having your child’s paternity questioned is insulting and demeaning, for a start. Can you imagine an official calling your paternity into question, which either accuses both parents of pretending a child is theirs or accuses the mother of infidelity?

More than that, it can be life-altering for the child and the whole family. It might even be potentially dangerous for the mother if the results prove that the presumed father is not in fact the biological father. As many as one in every 25 families could be vulnerable to a DNA testing earthquake, with unthinkable consequences for all involved.

How will the father react? What does this mean for the child? What are the consequences for the mother and for the presumed siblings? What will be the effect on their collective family life?

While the Home Office is not famous for its compassion nor general good manners, it did at one time prescribe common sense and sensitivity in these matters. When I last wrote about this issue in 2015, officials were instructed as follows:

Child not related to claimed father

The ECO must handle such cases with sensitivity as it may not be obvious whether the husband or other family members know of the true relationship and there may be serious repercussions for the wife and child if the information is disclosed (see illegitimacy below).

There may be any number of reasons why a claimed father may not be a child’s natural father including the death of the first husband, rape or adultery.

Illegitimacy

Where DNA evidence indicates that a child may be illegitimate, the ECO should:

- try to establish the truth of the family circumstances by interviewing the child’s mother as discreetly and sensitively as possible. Referring the case to the UK Visas and Immigration to interview the sponsor should be avoided.

If no information can be elicited from the mother, the best way forward may be to seek information from the sponsor’s representatives (depending on whether they are known to the ECO to be willing to respect the confidence of all parties).

If it appears that an illegitimate child has been brought up as a child of the family, it will normally be appropriate to admit the child under paragraph 297(i)(f). The fact that the sponsor may not be aware that the child is not his natural child should not preclude entry clearance.

The ECO should not routinely disclose information about the DNA report to the sponsor or other family members in cases involving the illegitimate children. However, under the Data Protection Act applicants and sponsors have a right to see personal information about themselves, which we may hold.

So, officials were explicitly guided to act discreetly and sensitively and to grant entry where it seemed the best and most sensitive way forward because the presumed father was not aware he was not the biological father.

This relatively enlightened guidance has disappeared from the gov.uk website. So far as I am aware, it has not been replicated in any of the guidance currently in force. An official who has demanded DNA evidence and received it, as far as we know, now has no official guidance on how to react or behave if the results are not those expected by the presumed parents.

Underuse of DNA testing in refugee family reunion cases

Meanwhile, DNA tests are under-used in cases where recognised refugees seek to exercise their right to be reunited with their families. Refugees are entitled to be joined by certain family members but may have difficulty in laying their hands on birth certificates or other documents to prove the family relationship. That is a useful arena for DNA testing and once upon a time the government funded it.

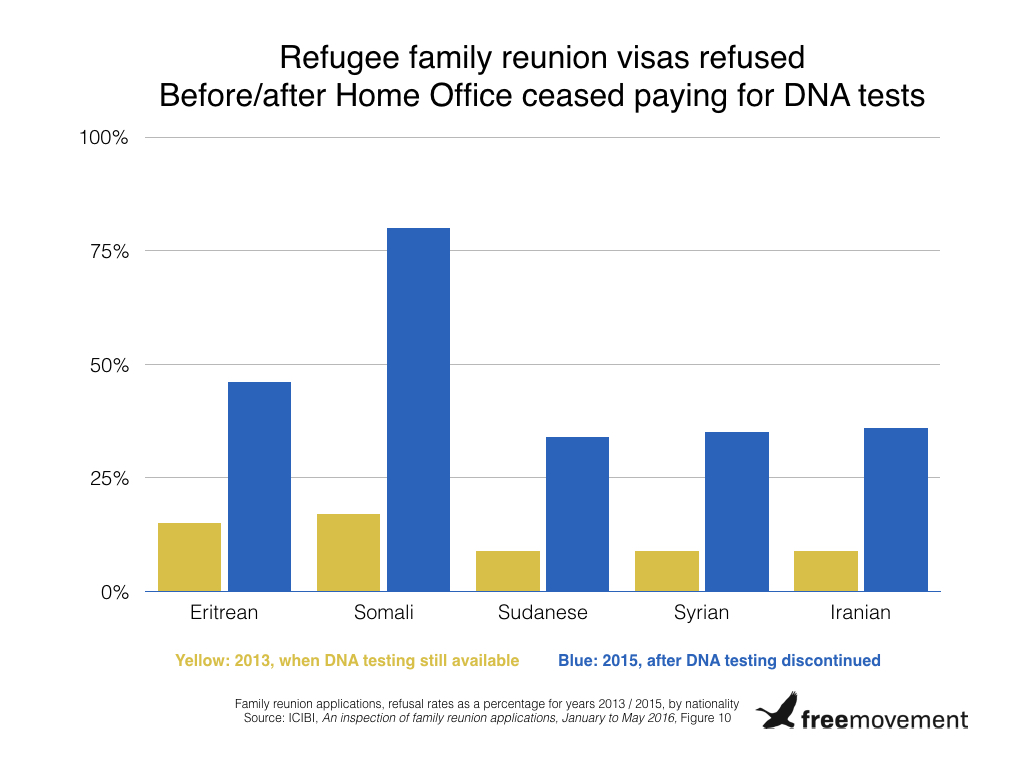

Home Office provision of DNA testing ceased in 2014. As the chart below shows, refusal rates in family reunion cases immediately soared.

The department is also refusing to help migrants entitled to family reunion under the Dublin III system prove their relationships through DNA testing.

Officials also attempt to ignore DNA evidence altogether where doing so would mean a person proves their case. In a nationality case that reached the High Court in 2015, the issue boiled down to whether the claimant could prove that she was the daughter of the man she claimed as her father. He was dead, so a direct DNA test was impossible. But DNA tests did show that the claimant was related as claimed to her four other siblings and that all five of them were the children of their claimed mother. Logically, then, the only way that the claimant might not be her father’s daughter was if her mother had secretly had a lover responsible for the birth of all five of the children.

This was precisely the position adopted by the Secretary of State in refusing to recognise the claimant as a British citizen. Mr Justice Walker quite rightly described its stance as “astonishing and grotesque … so far-fetched as to be absurd… a repulsive distortion of evidence”.

DNA testing can be a useful tool where there are child protection concerns, documentary proof is not available or there is genuine doubt as to a person’s identity for some other reason. Using DNA tests as a fishing expedition for a possible refusal is profoundly unethical but, as recent reports show, all too common.

SHARE