- BY Colin Yeo

Everything you need to know about the “hostile environment” for immigrants

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is the hostile environment?

The “hostile environment” for migrants is a package of measures designed to make life so difficult for individuals without permission to remain that they will not seek to enter the UK to begin with or if already present will leave voluntarily. It is inextricably linked to the net migration target; the hostile environment is intended to reduce inward migration and increase outward emigration.

The hostile environment includes measures to limit access to work, housing, health care, bank accounts and to reduce and restrict rights of appeal against Home Office decisions. The majority of these proposals became law via the Immigration Act 2014, and have since been tightened or expanded under the Immigration Act 2016.

As well as legislative measures in the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016, a number of administrative measures have also been introduced which should be considered an integral and complementary aspect of the wider hostile environment. Tougher immigration rules on overstaying, increasingly Byzantine application processes and steep increases to fees for immigration applications all appear to be deliberately intended to encourage migrants to leave the UK.

It is not that illegal entry or overstaying were not previously criminal offences; under the Immigration Act 1971 being knowingly unlawfully present in the UK or breaching the conditions of a visa are criminal offences. Convictions have steeply declined since a peak in 2005, however, and prosecutions have leveled out at around 500-600 per year. It seems the Home Office and/or police have neither the resources nor the will to enforce existing immigration laws. Similarly, the number of enforced removals of immigration offenders has fallen in recent years.

On the face of it, therefore, the hostile environment criminalises behaviour that is already criminal. It does go further, though, by also criminalising and penalising private individuals and entities who fail to enforce immigration laws in their dealings with other members of the public.

The defining feature of the new hostile environment is the abandonment of the pretence at central government enforcement of immigration laws and the move to reliance on indirect means to encourage compliance with and punish breaches of immigration control.

Origins and development of the hostile environment

In May 2012 Theresa May gave an interview to The Telegraph in which she promised to create a “really hostile environment” for irregular migrants in the UK. The choice of words was deliberate and those words came with something of a history.

She was quoted as saying:

The aim is to create here in Britain a really hostile environment for illegal migration … What we don’t want is a situation where people think that they can come here and overstay because they’re able to access everything they need.

The political origins of the phrase “hostile environment” lie within the Home Office and its responsibilities beyond immigration. Before that, the phrase was used as might be expected, to describe a country or part of a country that was quite literally “hostile” in the sense of dangerous and violent. For example, guidance on living and working in a “hostile environment” might be given to journalists visiting a war zone.

At some point during the prolonged policy reaction and re-evaluation following the 9/11 attacks on the United States, the phrase was co-opted within the Home Office to designate the policy intention to cut off funding and other “soft” support for terrorist activity.

The phrase was then later deployed for similar intent to describe measures to deal with serious and organised crime. This was something of a debasement of the strong language of hostility, but it is hard to fault the intention behind it.

Theresa May’s public adoption of the phrase in 2012 in the context of immigration was a quantum leap for the words. Now the “hostile environment”, previously referring to war zones, terrorists and serious criminals, was to be for ordinary migrants who fall the wrong side of an often arbitrary line separating lawful from unlawful residence.

The conflation of immigration with mass murder and very serious crime has a pernicious effect in delegitimising migration and migrants yet even after the application of the phrase “hostile environment” to immigration, the words were still being used in the context of terrorism and serious and organised crime.

At a policy level, the Coalition Government of 2010-2015 created in 2012 a “Hostile Environment Working Group” to devise new forms of hostility. This was renamed the more anodyne “Inter-Ministerial Group on Migrants’ Access to Benefits and Public Services”. The range of ministers appointed to the group reveals the extent of the ambition to make the hostile environment as far reaching as possible (see hostile environment inspection report):

- Minister of State for Immigration

- Minister of State for Care Services

- Minister of State for Employment

- Minister of State for Government Policy

- Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury

- Minister of State for Housing and Local Government

- Minister of State for Schools

- Minister of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

- Minister of State for Universities and Science

- Minister of State for Justice

- Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Health

- Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Transport

The potential scale and breadth of this intrusion into people’s private lives matches with Prime Minister David Cameron’s statement, on missing the net migration target yet again in February 2016, that the government was taking action “across the board” to bring immigration down.

On an operational level, the Interventions and Sanctions Directorate (“ISD”) is responsible for enforcing the hostile environment. It has existed since June 2013 and was reported in 2016 as having a staff of 146 and a budget in £5.5 million in 2015/16. Its stated purpose is to “to encourage greater compliance with the immigration rules”. A Freedom of Information request in 2013 revealed

The unit has overall responsibility for removing incentives for people to stay illegally and encourage those who are in the country unlawfully to regularize their stay or leave the UK. This is achieved by ensuring a range of interventions and sanctions are systematically applied to deny access to services and benefits for those who are unlawfully in the UK. The unit works closely with government departments and a range of other partners across the public and private sectors to identify those migrants accessing such services and benefits to which they are not entitled.

I&SU also has responsibility for the issuing and collection of financial penalties to those employers found to be employing illegal workers and the subsequent debt recovery process through third parties.

In short, the purpose of the Interventions and Sanctions Directorate is the indirect enforcement of immigration control through third parties.

The Interventions and Sanctions Directorate and the hostile environment it promotes arise from the opinion within the Home Office and central government that:

- Migration cannot be controlled as hitherto just at borders and entry points to the United Kingdom; and

- Prosecution and removal of those who breach immigration rules is not feasible.

Instead, immigration status checks have in essence been privatised.

The first step on this road was arguably the carrier sanctions scheme first introduced by the Immigration Act 1988, used to pressurise airlines and ferry companies to conduct immigration checks before allowing passengers to board their craft. It was extended to employers under the Asylum and Immigration Act 1996. Now the same approach has been extended into all aspects of people’s lives, in the process co-opting a range of private actors as immigration guards.

Employers, landlords, colleges, universities, banks, building societies, doctors and local government all have to conduct immigration status checks, incentivised by statutory duties, civil fines and criminal offences.

Who is affected by the hostile environment?

It is not just the scheming, deliberate or flagrant “illegal immigrant” of popular and Ministerial imagination who break immigration laws. Very minor errors and omissions can transform a migrant into an “unlawful immigrant” and can cast them into the twilight world of the hostile environment.

Jo Renshaw of Turpin Miller Solicitors describes this process as being “administrated into illegality.”

Apply one day late for an extension of your visa? Forget to include a passport photo with your immigration application? Include it but the background is wrong or you smile too much? Forget to answer one of hundreds of questions on a form? Home Office makes an error processing the payment for your immigration application and payment fails? These problems can and do cause migrants to become unlawfully resident.

And it is not only unlawful migrants who are affected by the hostile environment.

The privatisation of immigration control requires non governmental actors and public services to check the immigration status of all users and customers. An increasingly wide range of service providers and service users are therefore affected: employers, landlords, banks and doctors and everyone who has contact with them are all affected.

The effects are not equal; migrants, ethnic minorities, young people and women are disproportionately affected. But as we have seen following Brexit with the horrified reactions of mainly white EU migrants to the compulsory use of complex application forms, obscure rules on health insurance and sky high fees for citizenship applications, the UK’s hostile environment affects a wider and wider range of people.

Based on census data, it is thought that around 17% of UK residents do not possess a passport, most of whom are presumably British. Until recently, there was no need for a British citizen to possess a passport unless he or she wished to travel. The hostile environment, though, requires British citizens to prove their Britishness in a variety of every day situations and a passport is the only way to do so. Employees who have refused or failed to do so have been lawfully dismissed by employers.

What is the intention behind the hostile environment?

We have already seen what Theresa May wanted to achieve with the “hostile environment” from her initial interview in 2012:

- To discourage people coming to the UK;

- To stop those who do come from overstaying;

- To stop irregular migrants being able to access the essentials of an ordinary life.

At the time of the introduction of the Bill which was later to become the Immigration Act 2014 and thus the foundations of the “hostile environment” then Immigration Minister Mark Harper said the Bill would:

stop migrants using public services to which they are not entitled, reduce the pull factors which encourage people to come to the UK and make it easier to remove people who should not be here.

This is confirmed by the business plan for the Interventions and Sanctions Directorate for 2015/16:

Individually these interventions may be seen as just a nuisance but collectively, as we have already seen, they have the ability to encourage illegal migrants to voluntarily leave or never attempt to come to the UK illegally.

These statements tend to tell us how rather than why, though. Although it was never explicitly spelled out, there seem to have been two policy aims behind the hostile environment:

- Contribute to reducing net migration so that the arbitrary net migration target might be met; and

- Because it was morally right to punish irregular migrants by marginalising, isolating and further criminalising them.

As we will see, there is no evidence whatsoever that the hostile environment meets the first of these objectives. The Home Office has not even taken the trouble to research whether it might or to evaluate measures taken so far. Voluntary departures from the UK by irregular migrants actually seem to have fallen in recent years. Worse, the additional costs of the bureaucracy of conducting complex immigration checks and imposing charges on migrants is potentially outweighed by the costs.

As to the second objective, policy makers fail to recognise how easy it is to fall foul of complex Home Office rules and regulations and it assumes that the price of hostility is one worth paying: the creation of an illegal underclass of foreign, mainly ethnic minority workers and families who are highly vulnerable to exploitation and who have no access to the social and welfare safety net — access to a doctor when ill, access to a school for children, access to the police and to legal protections — that protects not just individuals but the fabric of society.

Access to employment: employer sanctions

The Immigration Act 2016 for the first time criminalises working in the UK without permission. Previously, if a person worked in breach of visa conditions that would have been an offence, but there was a relatively small group of individuals who had perhaps entered illegally and thus escaped the imposition of conditions in the first place. That ended with the commencement of section 34 of the Act on 12 July 2016.

The nature of the hostile environment, though, is that it is not just the migrant who is targeted but also the person with whom the migrant has contact.

It first became a criminal offence to employ a migrant subject to immigration control but who did not have permission to work under section 8 of the Asylum and Immigration Act 1996, long before the modern hostile environment was conceived. There were very few prosecutions, however, perhaps because criminalising such behaviour was disproportionate in many cases.

A new dual regime was introduced by section 21 of the Immigration, Nationality and Asylum Act 2006:

- An amended criminal offence requiring the employer to know the employee did not have permission to work; and

- A system of civil sanctions involving fines for employing a person without permission to work where the employer did not keep a record of the person’s immigration documents at the time the person was employed.

The number of prosecutions remained low under the 2006 Act; according to Hansard, there were less than 100 prosecutions in the five years to 2014. It is not known how many of these resulted in a conviction. Perhaps as a result, the offence was amended by the Immigration Act 2016 to enable easier successful prosecution. Employers can now be prosecuted under the amended provisions where they knew, or had reasonable cause to believe, that they were employing an illegal worker.

Under the civil penalty regime employers who fail to check the immigration status of an employee and who employ a person with no right to work in the UK will be subject to a civil penalty. The level of these penalties has steadily increased and now stands at up to £20,000 per worker.

The immigration status check is carried out using approved lists of documents published by the Home Office. Where the employer has correctly carried out the prescribed right to work checks before employment commences and has retained proper records, the employer will be exempt from civil sanctions if it turns out the employee did not in fact have a right to work.

However, as set out in the civil penalty guidance, undertaking those checks will not provide a statutory excuse where an employer

has conducted a check and it is reasonably apparent that the document is false (the falsity would be considered to be ‘reasonably apparent’ if an individual who is untrained in the identification of false documents, examining it carefully, but briefly and without the use of technological aids, could reasonably be expected to realise that the document in question is not genuine)

This means that even if an employer has undertaken the prescribed document checks, they can still be prosecuted and imprisoned for up to five years (increased from two years under the previous regime), if it is ‘reasonably apparent’ that a document is false. They also remain liable for the civil penalty of £20,000 per undocumented worker. Or both.

In reality, these provisions increase the risk for employers who employ individuals without a British or EEA passport. How many employers will be able to tell the difference between a genuine vignette in a passport, and one that is forged? Or, more importantly, how many will be willing to risk their business (and potentially their freedom) assessing a document that is not a British or EEA passport?

Access to love: restrictions on marriage and relationships

One of the changes wrought by the Immigration Act 2014 was a new system of marriage notifcation. The key features of the new system are:

- A new definition of “sham marriage”

- Notification for all marriages extended from 15 to to 28 days

- In all marriages involving a non EEA national, both parties to a marriage must attend in person to give notice at a designated Registry Office

- Specified evidence, including specified evidence of nationality, must be provided

- Any couple where at least one party is subject to immigration control and does not have settled status, or permanent residence under EU law, or is not exempt from immigration control, may be subject to investigation where there are reasonable grounds to suspect a sham

- The Home Office can extend the notification period to 70 days in order to investigate a marriage

The Home Office expected 35,000 marriages per year to be referred to the Home Office for consideration and 6,000 actual investigations to occur per year. A subsequent inspection report found that actual referrals and investigations were much higher. For the period March to August 2016 inclusive, a six month period, 23,948 marriage notices were referred to the Home Office team responsible, the Marriage Referral Assessment Unit, of which 17,818 were allowed to marry at 28 days and 6,130 were forced to wait the 70 day extended period.

Meanwhile, HM Passport Office statistics show that in 2016 a total of 808 couples applied to reduce the 28 day notice period, suggesting that it was an interference with at least some wedding arrangements.

It is clear that a significant number of people are affected by the new regime. The inspection report was critical, however, finding that the new notification system and powers had been poorly implemented and cases were not being decided within the 70 day time limit.

Access to housing: the “right to rent”

The “right to rent” scheme was introduced by the Immigration Act 2014 and has been further bolstered by the Immigration Act 2016. The main purpose of the scheme is to prevent individuals without any legal right to remain in the UK from accessing rented accommodation. In a further example of the outsourcing of immigration enforcement, landlords are now responsible for assessing whether or not a person is disqualified from occupying a property.

Section 22 of the Immigration Act 2014 requires private landlords to check whether a tenant (or occupier) is permitted to occupy a property by reference to their immigration status. Under the 2014 Act, any failure to comply with this checking regime would result in a penalty notice of up to £3,000 for the landlord.

Section 39 of the Immigration Act 2016 created a new criminal offence of knowingly renting accommodation to a person who does not possess the “right to rent.” Landlords and agents can be sentenced to terms of imprisonment of up to 5 years on indictment.

The Immigration Act 2016 also contain further provisions which make it easier for landlords to evict tenants who do not have a “right to rent” as a result of their immigration status. Section 40 of the Immigration Act 2016 enables but does not require landlords to evict those without lawful immigration status where a notice is received from the Home Office. In practice, this means that individuals the Home Office rightly or wrongly believes do not have a “right to rent” will have 28 days to vacate the property after they are served with a notice to do so by the landlord.

The notice is to be treated ‘as if it were an order of the High Court’ (s.33D(7) Immigration Act 2014, as amended), and those on the receiving end do not enjoy a right of appeal or the benefit of the Protection from Eviction Act 1977.

In short, landlords and agents have to check the status of all new tenants, risk a fine if they get it wrong or commit a criminal offence if they do it knowingly, and the Home Office can in effect render an existing tenant homeless by serving a notice on a landlord.

Access to health: NHS charging and data sharing

There is no evidence to suggest that there are “healthcare tourists” who deliberately come to the UK in order to make use of the National Health Service. Nevertheless, a huge bureaucracy has been created to make sure that these imaginary beings cannot get access to healthcare in the UK.

There are two elements to this aspect of the hostile environment:

- Introduction of immigration status checks for medical treatment on the NHS

- Sharing of patient data between the NHS and Home Office.

Under the National Health Service (Charges to Overseas Visitors) Regulations 2015 overseas visitors were already being charged by the NHS. New, stronger immigration status checks were to be introduced by means of new regulations in force from April 2017, although it does not appear that the regulations had in fact been laid at the time of writing.

There have been suggestions, however, that the administrative costs of attempting to collect fees are higher than the fees actually collected. Professor Martin McKee, Professor of European Public Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, gave evidence on 21 February 2017 to the House of Commons Health Select Committee that his research team had just completed

a study, which is under review at the minute, where we submitted freedom of information requests to every acute trust in England to ask them how much they spent collecting money from overseas patients and how much they recovered. Most of them were spending more money than they were recovering. They had a very low level of recovery, but as time went by they found they were often trying to recover from people who were entitled anyway.

Data sharing between the NHS and Home Office was formalised in a Memorandum of Understanding in January 2017. This facilitiates the transfer of limited non-clinical patient information relating to ‘immigration offenders’. The memorandum itself states that it is not ‘legally binding’ but ‘simply documents the processes and procedures agreed between the participants’. The NHS is permitted to disclose information under s.261 Health and Social Care Act 2012 where the disclosure is made in connection with the investigation of a criminal offence.

In the first eleven months of 2016 it was reported that 8,127 requests for patient information had been made by the Home Office.

There are a considerable number of migrants, lawful and unlawful, living in the UK. What are the consequences if these people and their children are unable or, for fear of the possible consequences, unwilling to access doctors?

Some conditions are strictly personal, such as cancer. Rather than such a condition being caught early and treated, the victim may die prematurely. There are reports of very ill patients wrongly being turned away by hospitals and pregnant women being afraid to seek antenatal care for fear of the consquences, with obvious risks to their health and the health of their babies.

Other conditions are contagious or have wider implications. It is critically important that vaccination rates are very high, for example, and that conditions such as AIDS or tuberculosis are identified and treated. By denying healthcare to afflicted individuals and/or making them scared of going to the doctor, it is arguable the hostile environment represents a risk not just to individuals but to public health. On top of that, there may be a financial cost to the imposition of the charging regime, suggesting that the measures are adopted because they are considered morally “right” rather than because they are effective in practical terms.

Access to banking: opening and closing current accounts

In her 2012 interview announcing the “hostile environment” Theresa May said that

If you’re going to create a hostile environment for illegal migrants … access to financial services is part of that.

Sections 40 to 42 of the Immigration Act 2014 created a scheme intended to prevent individuals from opening bank accounts if they do not have permission to live in the UK. The bank or building society is required to check the status of each new potential customer with a specified anti-fraud organisation or a specified data-matching authority.

Those acting as the immigration officials in this case are the banks and building societies which hold the accounts, and who must undertake an immigration status check on any person applying for a current account.

An inspection report on the operation of these provisions found that the organisation designated for checks was CIFAS, but that the data held by CIFAS was not always accurate because the underlying Home Office information was not accurate. In a sample size of 169 cases, inspectors found that 10% of the people on the list were wrongly listed because they had leave to remain, an outstanding application for leave or an outstanding appeal.

There are already reports that it is very difficult for individuals with unusual forms of identity, such as refugee status documents, to open a bank account because of the additional administation involved for the bank concerned.

https://twitter.com/SimonNeville/status/845360266195939329

The Immigration Act 2016 develops the banking rules even further. New sections 40A to 40H of the Immigration Act 2014 (inserted via Schedule 7 of the Immigration Act 2016) will require banks and building societies to make checks on existing account holders if requested to do so by a specified body, and to notify the Secretary of State if the person may be a ‘disqualified person’ (basically, an irregular migrant).

The Secretary of State then has the power to either freeze the account of that person (s.40D), or oblige the bank or building society to close the account (s.40G).

The intention is clear. At the Conservative Party conference in October 2016, Home Secretary Amber Rudd trailed the new banking measures and said

Money drives behaviour, and cutting off its supply will have an impact.

A draft version of the Immigration Act 2014 (Current Accounts) (Excluded Accounts and Notification Requirements) Regulations 2016 was laid before Parliament on 7 November 2016 with an expected commencement date of 31 October 2017.

It is one thing to be prevented from opening a bank account. It is quite another to have your existing account closed and your funds frozen, preventing you paying your rent or mortgage or accessing any of your money. Given that around 10% of those reported by the Home Office as being illegal are not, the consequences of these new provisions could be very damaging indeed for a signficant number of individuals.

Access to roads: refusal and revocation of driving licences

Under the Immigration Act 2014 (ss.46-47) the government sought to restrict access to driving licenses for non-EEA nationals. Anyone without a license from an EEA or other designated country needs to demonstrate that they have six months leave in the UK when applying for a licence.

There has been some suggestion that depriving illegal immigrants of driving licences might reduce road safety and increase the incidence of “hit and run” accidents. This seems unlikely to deter the Home Office from pursuing this policy, however.

The Act also conferred on the DVLA a power to revoke a license when issued to a person who does not have leave to remain. Where a person’s licence is revoked on this basis, it is not open to them to argue in an appeal against the revocation that leave should have been granted to them, or that they have been granted leave after the date their licence was revoked.

The inspection report on the hostile environment examined the use of these powers. The Home Office made 9,732 revocation requests to the DVLA in 2015, all but meeting the target of 10,000 per year. However, some of these were wrongly revoked: the person actually qualified for a driving licence after all. In 2015, 259 licences then had to be reinstated. In the meantime, those affected would have been unable to drive or would have committed the strict liability offence of driving without a licence.

A further problem emerged with notice of revocation being sent to individuals who had left the UK, meaning the notice was unlikely to be received. Such individuals would be committing an offence if they were to drive on return to the UK, perhaps without ever knowing that their licence had been revoked.

The Immigration Act 2016 went further by introducing a power for the entry and search of premises for a driving license if it is reasonably believed that a person who is not lawfully in the UK holds it and creating a new offence of driving when unlawfully in the UK. It creates rights for law enforcement to detain the motor vehicle in question, as well as the offender.

Complexity of the rules: ‘administered into illegality’

One of the principles of the rule of law is that the law “must be accessible and so far as possible intelligible, clear and predictable” (Tom Bingham, The Rule of Law, 2010)

Immigration law is anything but accessible, intelligible, clear and predictable.

In a series of cases senior judges have condemned the complexity of UK immigration law. For example, in the case of Pokhriyal v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2013] EWCA Civ 1568, Jackson LJ stated that the “provisions have now achieved a degree of complexity which even the Byzantine emperors would have envied”.

In Hossain & Ors v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2015] EWCA Civ 207Lord Justice Beatson says at paragraph 30:

The detail, the number of documents that have to be consulted, the number of changes in rules and policy guidance, and the difficulty advisers face in ascertaining which previous version of the rule or guidance applies and obtaining it are real obstacles to achieving predictable consistency and restoring public trust in the system, particularly in an area of law that lay people and people whose first language is not English need to understand.

In Singh v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2015] EWCA Civ 74Underhill LJ said:

I fully recognise that the Immigration Rules, which have to deal with a wide variety of circumstances and may have as regards some issues to make very detailed provision, will never be “easy, plain and short” (to use the language of the law reformers of the Commonwealth period); and it is no doubt unrealistic to hope that every provision will be understandable by lay-people, let alone would-be immigrants. But the aim should be that the Rules should be readily understandable by ordinary lawyers and other advisers. That is not the case at present. I hope that the Secretary of State may give consideration as to how their drafting and presentation may be made more accessible.

See also SI (India) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2016] EWCA Civ 1255 and Mirza v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2016] UKSC 63.

The problem is caused partly by repeated re-amendment of the underlying legislative provisions of immigration law, which are now principally spread out between Acts of Parliament from 1971, 1999, 2002 and 2014, each of which has been amended by later legislation, sometimes repeatedly so that the amendments have been amended and re-amended.

Migrants, lawyers and judges are now faced by rules which are uniquely set out in a non-sequential fashion, breaking a drafting convention that can be traced to at least the Ten Commandments. These rules are so difficult to comprehend that it is hard even to describe their complexity. It is easiest to give a commonplace example.

Appendix FM of the Immigration Rules applies to family members; it is arguably the single most important section of the rules for which it is arguably most important that the rules are clear.

If a spouse or partner is applying for leave to remain in the UK, some of the rules are set out at, for example, section R-LTRP. These rules cross reference requirements set out in section E-LTRP and EX.1. How does one find these sections? The paragraphs are not set out in any numerical or alphabetical sequence. One has to swim through the alphabet soup until serendipity strikes.

It is not just finding, cross referencing and understanding the legal requirements that is complex. The requirements themselves are sometimes incredibly arcane.

Only evidence in a certain format will be accepted, for example. If you have an online bank account, you will need to get each printed page stamped by a bank, but the bank may well refuse to do so. If a photograph is wrong, for example because of too much smile or an incorrect background, the entire application can be rejected, the (huge) fee forfeited and the applicant suddenly rendered an overstayer.

This trend towards tortuousness no doubt began as a result of incompetence and haste. The continued layering of new complexity on old has now to have been opportunistically embraced as an expression of the hostile environment. The point has been reached where the decision to continue to make immigration law more complex rather than more simple has become a tool of immigration policy.

Cost of immigration applications: priced out

The cost of making an immigration or nationality application has risen extremely steeply in recent years. Increases of 20% or 25% per year are now standard, bringing the current cost of an application for Indefinite Leave to Remain in 2017 to £2,297.

The actual cost of processing such an application is £252, so the Home Office is generating considerable income from each application.

The cost of settlement is only one of the last steps in a long journey of applications, though. The total costs of applying to enter the UK as a spouse are much higher once all the different applications and fees are taken into account:

| Initial application | £1464.00 |

| Extension application | £993.00 |

| NHS surcharge | £1000.00 |

| Settlement | £2297.00 |

| Naturalisation | £1163.00 |

| TOTAL | £6917.00 |

Fees were only introduced for in-country applications in 2003 and the increase only began in earnest in 2007, when for example a postal application for Indefinite Leave to Remain was increased from £335 to £775 and an application for naturalisation as a British citizen from £200 to to £575.

The principal driver for the increases appears to be pressure on the Home Office budget. The Autumn 2015 Spending Review indicated that the Home Office was aiming to achieve “a fully self-funded borders and immigration system.” Savings were needed but

[t]he remainder will be funded through targeted visa fee increases, which will remove the burden on the UK taxpayer while ensuring the UK remains a competitive place for work, travel and study internationally.

There seems little doubt, however, that as far as Ministers are concerned a welcome side effect of the steep fee increases is that this “prices out” migrants of modest means. There is certainly anecdotal evidence that families struggle to afford the necessary fees and the earnings threshold for spouses and some are driven to explore alternative migration routes as a consequence.

The new Immigration Skills Charge introduced on 1 April 2017 is more explicitly aimed at reducing immigration. It was introduced at a level of £1000 per year per worker and is due to be doubled after the next election (Conservative Manifesto 2017). Introducing the implementing regulations, the Minister, Lord Nash, said

Through the charge we want to incentivise employers to think differently about their recruitment and skills decisions and the balance between investing in UK skills and overseas recruitment … There are many examples of good practice, but it seems that some employers would prefer to recruit skilled workers from overseas rather than invest in training UK workers.

The Migration Advisory Committee, appointed by central Government to advise on immigration policy questions, recommended that £1,000 would be

large enough to have an impact on employer behaviour and that this would be the right level to incentivise employers to reduce their reliance on migrant workers.

The Immigration Skills Charge is explicitly intended to make foreign workers uncompetitive in order to reduce immigration. It is a classic “tariff” in intention and effect.

Access to legal remedies against Home Office mistakes

Where the state makes a wrong decision, it is desirable that the private citizen have ready redress to be able to correct that mistake. This is all the more important where the mistake affect fundamental rights and the private sphere.

Tom Bingham’s sixth rule of law is that

Means should be provided for resolving, without prohibitve cost or inordinate delay, bona fide civil disputes which the parties themselves are unable to resolve”

There are a number of ways in which the right of redress for incorrect Home Office decisions about immigration status has been undermined in recent years:

- Rights of appeal to the immigration tribunal have been curtailed by reducing the number of decisions which can be appealed and the grounds on which an appeal can be brought.

- More litigants are forced to appeal after rather than before they are removed, at the risk of rendering their appeal impossible.

- Fees for immigration appeals were briefly increased very substantially before the Government backtracked following a threat of litigation.

- Waiting times for immigration appeals have been permitted to grow considerably, standing at 83 weeks for some appeals at the time of writing.

Where there is no right of appeal to a tribunal, an application for judicial review can sometimes be made instead. This is not a “merits” appeal, though, where the judge can freely make his or her own mind up about the issue in dispute and order that a visa is granted or refused.

An application for judicial review involves merely review of the lawfulness of a Home Office decision; it is only on public law grounds that a decision can be quashed, such as failure to take into account a material consideration or making a decision no reasonable decision maker could have reached. Even where a decision is found unlawful, the decision maker is merely required to make a new, lawful decision, and in some cases the new decision is in substance the same as before but with different reasons expressed.

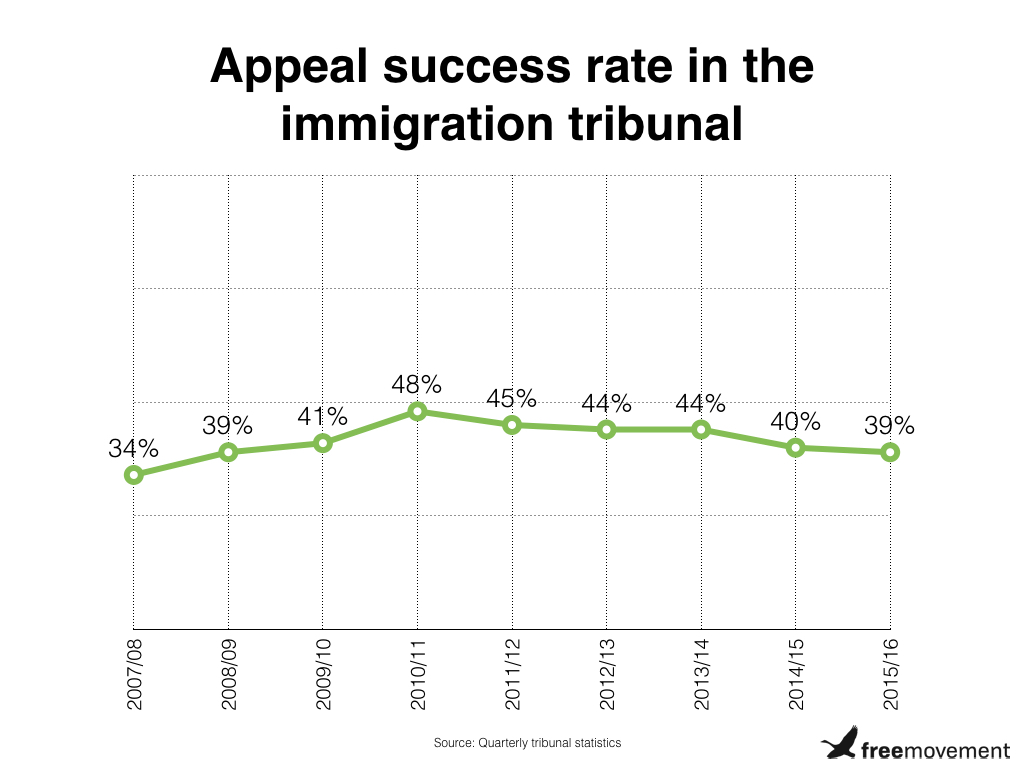

It is not that Home Office decision making has improved. If rights of appeal had been removed from vexatious time wasters, as is suggested whenever such measures are introduced, then we would expect to see the success rate of the remaining appeals increase as the unmeritorious appeals are removed from the system. There is no evidence for this; instead, the success rate has if anything declined, suggesting that , if anything, it is the meritorious appellants who have been filtered out.

Discouraging migration or a moral crusade?

The stated purpose of the hostile environment is to drive down inward migration to the UK by making it as unadvantageous, risky, expensive and inconvenient as possible. The hostile environment is also intended to encourage migrants already in the UK to leave by administering many into irredemable illegality and making their lives as marginal and difficult as possible.

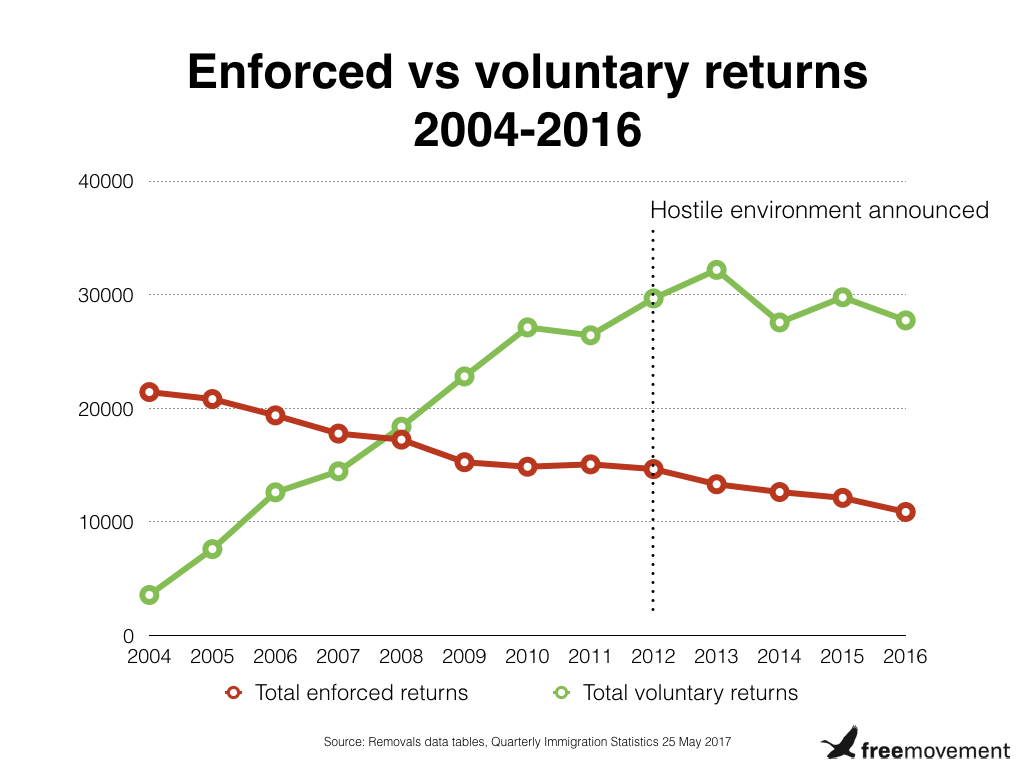

There is little to no evidence that the hostile environment actually works, however. The available data certainly does not show an increase in either enforced or voluntary returns since the hostile environemnt was announed in 2012.

Part of the reason that there is no evidence is that the Home Office is not interested in the question of whether it actually works or not.

In the inspection report on the hostile environment, inspectors found that (para 7.7)

There was no evidence that any work had been done or was planned in relation to measuring the deterrent effect of the ‘hostile environment’ on would-be illegal migrants.

No targets had been set by ministers for voluntary returns or net migration and there was no pressure to deliver specific outcomes.

Even if there was research to show that the hostile environment was not effective, it would not be abandonned:

This was because it was the right thing to do, and the public would not find it acceptable that illegal migrants could access the same range of benefits and services as British citizens and legal migrants.

The hostile environment is overtly intended to discourage migration but there is no evidence to suggest it works, no targets have been set, no evaluation is being commissioned and the expense of implementation may outweigh the income generated.

On closer inspection the hostile environment is more akin to a moral crusade.

Discrimination against migrants and ethnic minorities

Ministers state that the hostile environment is aimed at illegal immigrants. There are concerns that the effects are far more widely felt.

The Joint Council on the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI) produced a report on the impact of the “right to rent” changes. The study found that:

- foreign nationals and British citizens without passports are being discriminated against in the private rental housing market

- 51% of landlords surveyed said the scheme would make them less likely to consider letting to foreign nationals

- 42% of landlords stated they were less likely to rent to someone without a British passport as a result of the scheme—this rose to 48% when asked to consider the impact of the criminal sanction

- in a mystery shopping exercise, an enquiry from a British Black Minority Ethnic tenant without a passport was ignored or turned down by 58% of landlords

The JCWI is not alone in making these findings. A report by Shelter reflected a wide-ranging poll of private landlords in July 2015. The survey found that

…more than four in ten (44%) of those making letting decisions said the new law would make them less likely to let to people and families who ‘appear to be immigrants’

In a separate survey by the Residential Landlord’s Association (RLA), 43% of respondents stated that they were less likely to rent to ‘those who do not have a British passport’, because they feared criminal sanctions for getting it wrong under the legislation.

Even the Home Office’s own evaluation found that a higher proportion of Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) “mystery shoppers” were asked to provide identity and immigration documents during rental enquiries (which very obviously amounts to discrimination on the grounds of race: “I need to see your papers because you are black”) and that

comments from a small number of landlords reported during the mystery shopping exercise and focus groups did indicate a potential for discrimination.

The JCWI report was published prior to the coming into force of the 2016 Act, and so does not address the newly established criminality provisions. However, the report raises two further issues about the latest addition to the hostile environment.

Firstly, the criminal offence of renting to a person without the right to rent is broadly drawn and creates issues for legitimate schemes that provide safe housing for vulnerable individuals such as victims of abuse, as well as for those with friends and family living with them. The Government response to this issue has been to suggest that such people, even though they fall within the terms of the offence, are not likely to face prosecution as the scheme is designed to target ‘rogue landlords’ who exploit migrants.

The Government has deliberately created an overly broad criminal offence which the Government does not intend to have universal application and which will instead be mitigated by selective prosecution. This is a recipe for discrimination and abuse of power by officials.

Secondly, the eviction provisions, allowing landlords in some cases to evict without a court order, leave individuals, including children, entirely at the whim of the Home Office and the accuracy of the information it holds.

This last point is crucial: sometimes a person’s immigration status is clear. However, often it is not. Remi Akinyemi, for example, featured recently on Free Movement, is a man whose immigration status was misunderstood by himself, his family, the Home Office, two different tribunals, and his own legal team before he was Richard Drabbled in the Court of Appeal, and it was finally established that he was not unlawfully in the UK. This is not uncommon, and reports by the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration routinely criticise the quality of data entry and the data itself held by the Home Office.

Creation of an underclass

If those migrants, ethnic minorities and others affected by the hostile environment and/or deprived of services under its direct and indirect effects do not actually leave the United Kingdom, what happens to them? For those on the receiving end of these measures, this is the stuff of nightmares, especially where the Home Office gets it wrong.

The effects of the different provisions of the hostile environment might include, rightly or wrongly given that the data on which enforcement is based:

- Closure of a bank account, leading to loss of home, job and more.

- Eviction from home because of a notice served by the Home Office on a landlord. There are no provisions protecting children or families.

- Committing the strict liability offence of driving without a license if notice is served to the wrong address.

- Becoming an unlawful immigrant (which is a criminal offence) because of an innocent mistake on an application form, then being subject to a ban from re-entering the UK

- Being forced to live in another country with foreign spouse because rules and fees are unaffordable

It seems likely that the small number of existing “rogue” employers and landlords at whom the measures are purportedly aimed will be those least likely to comply; these individuals are by definition ignoring existing laws. The burden of regulation will really be borne by the vast majority of employers and landlords who are reputable. They will try to comply with the new laws, although in so doing they incur considerable administrative costs and may discriminate against foreigners and ethnic minorities in order to limit their exposure to the risk of a fine.

The direct effects of the hostile environment will no doubt be felt by some illegal immigrants, who will lose their homes, jobs, money and everything else. Whether they will as a result then leave the United Kingdom is questionable. With nothing more to lose, they have little incentive. Instead, they may enter the black economy, working cash in hand, staying in slum landlord style accommodation below the official radar and with no employment or other rights, vulnerable to exposure to the authorities at any time.

The indirect effects of the hostile environment — higher administrative costs, requirements to produce identity papers at every turn and the creation of an underclass of illegal immigrants — will be felt more widely.

As final food for thought, let us consider the definition of “harassment” at section 26 of the Equality Act 2010

(1) A person (A) harasses another (B) if—

(a) A engages in unwanted conduct related to a relevant protected characteristic [e.g. race/nationality], and

(b) the conduct has the purpose or effect of—

…

(ii) creating a intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for B.

That the language adopted by the Home Secretary herself and by civil servants actually forms part of the legal definition of “harassment” in equality law is astonishing. That there is clear evidence of a wider risk of discrimination against legal foreign nationals, ethnic minorities and others and that the measures are pursued regardless is also genuinely astonishing.

Sadly, that there is no evidence that the stated aim of the “hostile environment” can be met by the measures adopted is somewhat less surprising.

SHARE