- BY Colin Yeo

Yvette Cooper and Home Office immigration ministers cleared out in reshuffle

Last weekend’s reshuffle saw Yvette Cooper replaced as Home Secretary by Shabana Mahmood, who was previously the Lord Chancellor. In addition, Angela Eagle, previously the Minister of State for Border Security and Asylum, and Seema Malhotra, previously the Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Migration and Citizenship, have both been moved to other departments.

That means the entire ministerial team responsible for immigration and asylum has been replaced. The two new immigration ministers appear to be Sarah Jones and Alex Norris, although no announcement had been made at the time of writing as to who was going to take which job. We’ll update this article when we find out.

Yvette Cooper’s tenure of the Home Office lasted just over a year. Politically, it was not a good period for the Home Office. Small boat crossings rose as did asylum hotel occupancy. These have become two of the key issues on which the success of the government is judged, at least in the short term and in contemporary headlines.

Behind the scenes, though, the fundamentals improved.

Small boat crossings are beyond the direct power of the UK government to change; the “smash the gangs” rhetoric is a fantasy. But Cooper negotiated a returns deal with France and, apparently, also an as-yet unannounced one with Germany. This entirely eluded previous Conservative governments, which nonchalantly managed to exit the Dublin returns agreement at the same time as exiting the European Union. The returns deals are one-in, one-out and are only pilots. But returns deals with the EU represent the best and most realistic possibility of addressing small boat crossings, in my view.

Although this also needs combining with a functioning asylum system. The best any government can do to appear in control of asylum is to rapidly process claims, rapidly integrate those who are granted asylum and rapidly return those whose claims fail.

Here too, Cooper made some progress behind the scenes. The massive initial decision backlog left behind by the previous Conservative government was diminishing. Initial decision-making was becoming faster. And returns of failed asylum seekers, which the previous Conservative governments had all but abandoned, have risen rapidly.

But there were two massive omissions, which ultimately seem to have proven fatal to Cooper.

Asylum appeals: what can be done?

The most politically important of these was the failure to speed up asylum appeals. An asylum claim is not truly processed until the appeal is finally concluded. During the appeal process, the appellant remains supported by the Home Office, principally at the moment in an asylum hotel. And there is a massive and growing appeals backlog that is totally beyond the government’s control right now. This means that the number of asylum seekers in hotels is now growing.

There are two causes. I wrote about these back in January, incidentally, which was picked up recently by Georgina Quach in the FT. I tentatively predicted, with some back of an envelope calculations, that the appeals backlog could reach 100,000 by the end of 2025.

One cause is the surge in decisions caused by working through the initial decision backlog. Some of these decisions were always going to be refusals. Refusals means appeals. So there was always going to be a surge in the number of appeals, albeit smaller than the number of initial decisions made.

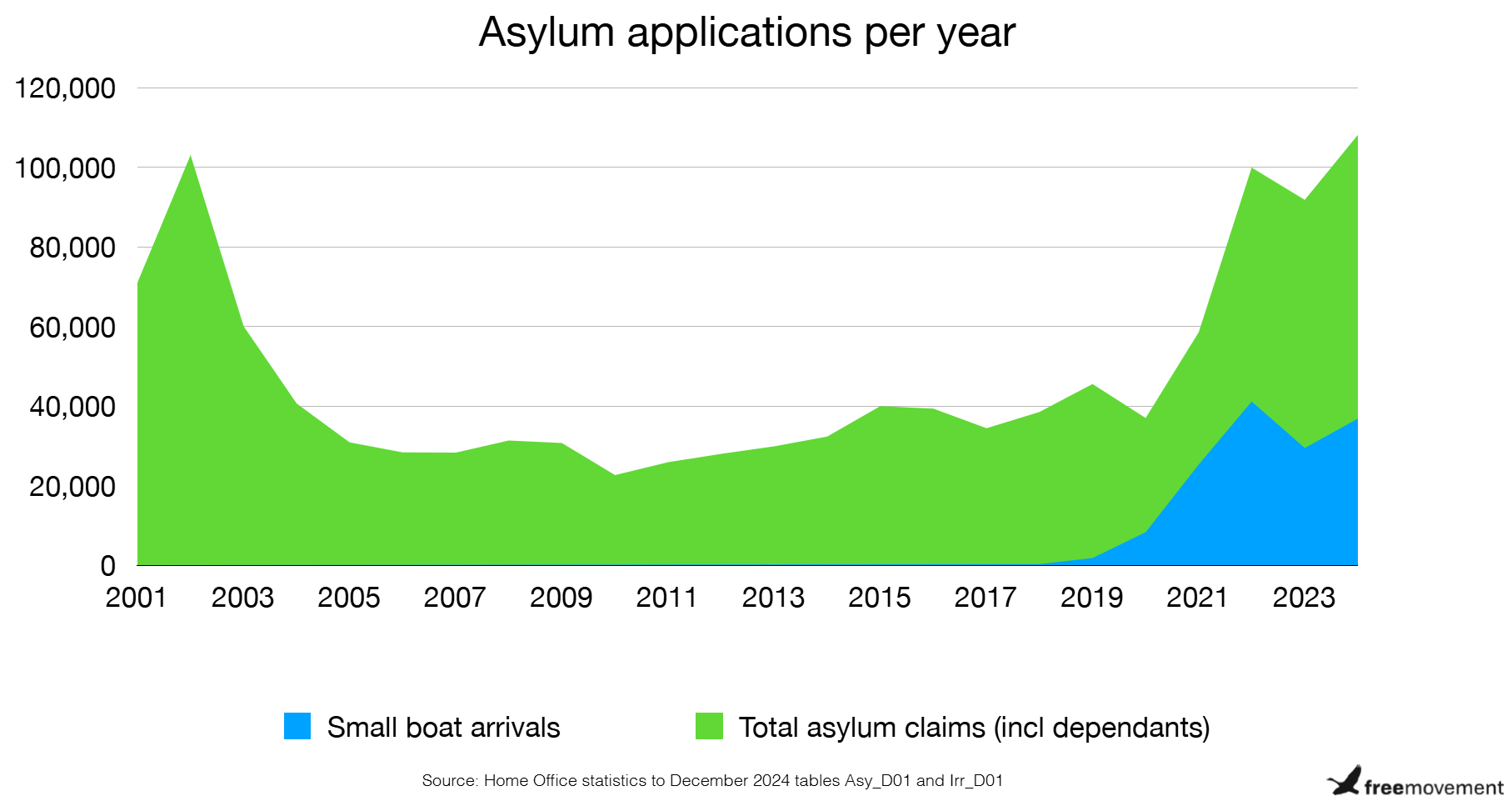

The other cause is the structural increase in the number of asylum claims. Record numbers of asylum claims are now being made, higher even than the early 2000s. Some of those claims are always going to be refused, meaning more appeals.

One obvious measure open to the government is to stop refusing so many asylum claims. It is only refusals that generate appeals. But the percentage of refusals has rapidly increased, leading to even more appeals being lodged than would otherwise have been the case. We do not know what the allowed rate will be for these future appeals but it has been hovering at around 50% for several years now. With appeals taking well over a year to process already — a period that can only lengthen as things stand — that means half of those appellants are pointlessly stuck in asylum hotels for that time only to win their cases in the end anyway.

The Home Office as an institution seems to believe that a high asylum grant rate acts as a pull-factor for asylum seekers. That seems potentially plausible although there is no research of which I am aware to back it up. But there are surely far more important pull-factors, including language, the lack of any returns agreement with EU countries and the extraordinarily prolonged nature of the current UK asylum appeal process. At least in the short term, getting the asylum appeals process under control should be more of a priority and that means granting asylum to a higher proportion of claimants so that there are fewer appeals to process.

With so many asylum claims being made and decisions following, that inevitably means a lot of appeals. If asylum claims ran at around 80,000 per year and the grant rate around 50%, that would mean around 40,000 appeals need to be heard each year. Actually, asylum claims are currently running at over 110,000 per year and there is also the backlog of 50,000 appeals to work through.

The immigration tribunal — technically the Immigration and Asylum Chamber of the First-tier Tribunal — managed to conclude 18,500 appeals last year, which was double the total of the year below. But that is still considerably less than half of the amount needed.

So, what could be done to increase the number of appeals concluded per day?

Immigration judges currently hear a maximum of two asylum claims per day. Some get adjourned and some are successfully appealed so the actual number concluded is less than two per judge per sitting day. As things stand, existing judges are, basically, unwilling to do more than two asylum cases per day. Hearing the cases takes hours (mainly because of largely pointless and interminable Home Office so-called cross-examination). Reading the refusal letter, skeleton argument, witness statements, interview notes, expert reports, country information and other documents and then producing a high quality (i.e. non-appealable) written decision takes more hours.

There is a limited number of judges and further recruitment on current selection criteria seems to have reached a natural maximum. Who would want to be an immigration judge now, quite frankly, given the media attacks?

The current President of the tribunal, Melanie Plimmer, has tried to streamline the process by means of a new practice direction seeking to limit the length of expert reports and promote on-the-day decisions. This has caused resentment amongst the judges, I understand.

Changing the procedure rules governing the hearing of asylum appeals lies outside the direct control of the government because it is managed by the Tribunal Procedure Committee. The previous Conservative government legislated to impose a duty on that committee to introduce certain rules but that does not seem to have borne fruit yet, for reasons I confess I haven’t looked into.

There is also a shortage of lawyers able and willing to represent asylum seekers. Who would want to be an immigration lawyer now, quite frankly, given the media attacks, the relentless administrative grind and the appallingly low pay? Legal aid rates are, belatedly, going to rise but the fact is that qualified lawyers can have a far better life if they work in other areas of law.

Cooper as Home Secretary was going to introduce a legal duty on judges to hear asylum appeals within six months but offered no new resources or solutions to the problems outlined above. It was the sort of “make it so” legislative fantasy indulged in by previous Conservative governments.

Something pretty major needs to happen to appeals because the current situation is clearly unsustainable. The appeals backlog is growing, not diminishing. It is no wonder the government is considering radical reform, which appears to mean removing asylum appeals from the existing tribunal system entirely. Whether this can really solve the underlying problems remains to be seen. Where will the new adjudicators come from, what will the recruitment criteria be, will they be appointed by the Home Office or the Ministry of Justice, what will be the nature of a new model asylum appeal hearing, where will they be heard and will there be an effective right to legal representation? Who knows.

Refugee integration: ignore at your peril

The other major omission during Cooper’s tenure as Home Secretary is the failure to ensure smooth integration of recognised refugees. This is less of an urgent priority than ending the use of asylum hotels. But it is important if we want to live in a decent society whose members are treated equally and in which everyone has a decent opportunity for themselves and their children. Failing to integrate refugees leads to resentment, poverty and isolation. It undermines growth, social cohesion and worker’s rights.

The basic problem is that when a refugee wins their case, they have a short time before they are evicted from Home Office accommodation. Many become homeless and dependent on the assistance of the local authority where they were previously accommodated. With the surge in decisions and overall increase in asylum claims, local authorities have been overwhelmed.

There have been steps in the right direction, such as temporarily lengthening the move-on period for refugees leaving Home Office accommodation. Some help seems to have been offered to local authorities.

The fundamental problem remains, though: it is unlikely that an asylum seeker will be able to find a job and accommodation in the period between the grant of asylum and the eviction from Home Office accommodation.

Allowing asylum seekers to work after six months waiting for a decision would mean fewer becoming homeless when they are granted asylum; they would already be able to stand on their own feet. Permanently giving them a bit more time between receiving their immigration papers and evicting them might reduce the number who end up homeless. A support and welcome package for newly recognised refugees should be introduced, which would save money in the long run.

Will Shabana Mahmood and her new team be able to make more progress? It looks like they will benefit from some of the quiet progress made by Cooper and her team. But there is a lot to do, particularly on appeals and on making sure the returns agreements work in practice.

SHARE