- BY Grace Brown

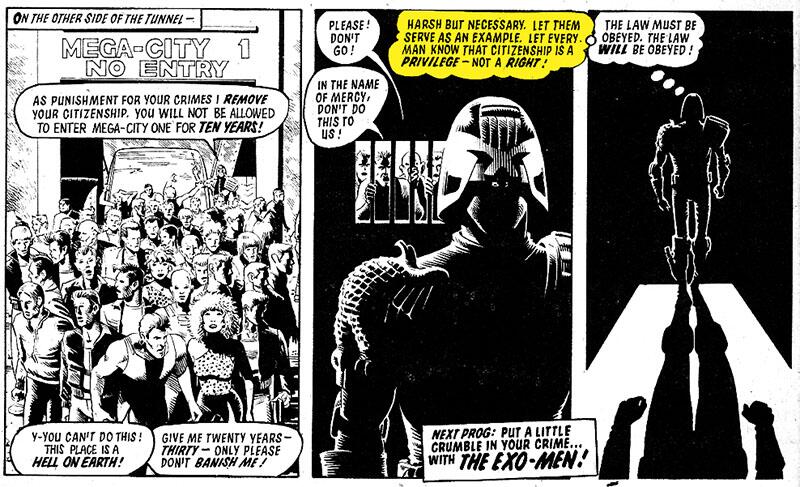

Right to citizenship? Supreme Court to decide

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

The Supreme Court will today hear a case, Secretary of State for the Home Department (Respondent) v B2 (Appellant), concerning the definition of statelessness in international law and in which the Secretary of State’s power under section 40 (2) of the British Nationality Act 1981 to deprive a naturalised British citizen of that status will be examined. The case could determine the limits of the Secretary of State’s power to deprive a person of British nationality.

Although the appellant was born in Vietnam he had barely lived in that country, having been taken to Hong Kong by his parents whilst he was still an infant and thereafter resided in the UK from about the age of 6, acquiring British nationality at the age of 12. In 2011 the Secretary of State determined that he should be deprived of his British citizenship on grounds that this would be “conducive to the public good”.

The Vietnamese government declined to accept that the appellant was a Vietnamese citizen and subsequently refused to accept him as such. This meant that, arguably, an order under s.40 of the 1981 Act could not be made, not least because it would be inconsistent with the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness “if such deprivation would render him stateless”.

The appellant appealed to the Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC) — which hears national security cases involving immigration issues and which can include secret evidence and argument of which the claimant is unaware — in 2012 and in a preliminary hearing held in June 2012. The panel, comprising Mr Justice Mitting, Upper Tribunal Judge Allen and Mr P. Nelson, who heard expert evidence from two Vietnamese lawyers, allowed the appeal on the basis that the effect of the decision would be to render the appellant stateless.

After considering the Nationality laws of Vietnam and the appellant’s status under those laws, the Court of Appeal overturned SIAC’s decision concluding that although the appellant was de facto stateless, he was not de jure stateless and therefore the order depriving him of nationality was lawful; see Fransman’s British Nationality Law, third edition, paragraph 25.4 and Abu Hamza v The Secretary of State for the Home Department (SIAC, 5 November 2010).

The Supreme Court will have to determine whether the Secretary of State can disagree with a foreign State where it concludes that a person is not a national of that country. If the Supreme Court finds in the Secretary of State’s favour, that the Secretary of State can disagree with the foreign State as to whether or not the person is a national of that foreign State, the position for the individual where they will not be accepted by the other State and have been deprived of the British nationality is far from clear and such an outcome could be inconsistent with international law.

4 responses

Humble (hard working) public servant that I am, I struggle to understand how the Court (we’re it to rule in SSHD’s favour) has any power to order the Vietnamese government to alter its position and in turn what is hoped be achieved by this case?

It is a bit of a puzzler!

The creation of another “illegal immigrant” who cannot be removed from the UK?

Clearly they are attempting to interfere into the internal affairs of independent states and their independence