- BY Josie Laidman

Legal aid for asylum seekers is broken

THANKS FOR READING

Older content is locked

A great deal of time and effort goes into producing the information on Free Movement, become a member of Free Movement to get unlimited access to all articles, and much, much more

TAKE FREE MOVEMENT FURTHER

By becoming a member of Free Movement, you not only support the hard-work that goes into maintaining the website, but get access to premium features;

- Single login for personal use

- FREE downloads of Free Movement ebooks

- Access to all Free Movement blog content

- Access to all our online training materials

- Access to our busy forums

- Downloadable CPD certificates

Table of Contents

ToggleThe system of legal aid for asylum seekers in the UK is broken. The legal advice and representation available is becoming so inadequate that it may breach the state’s human rights obligations and will inevitably lead to significant miscarriages of justice. The underlying problem is that legal aid no longer provides a sustainable income for qualified legal providers and advocates, meaning that more and more providers are simply giving up. Large charities the Immigration Advisory Service and Refugee Legal Centre went bust a decade ago because they couldn’t pay their bills on legal aid. The current haemorrhaging of lawyers out of the sector is more of a slow burn, but it is very real.

Procedural obligations on the state under Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights can require the provision of legal aid in immigration cases. So do (albeit indirectly) articles 2 and 3. But is the UK upholding its obligations? This post looks at legal aid in the general context of asylum applications in the UK, as well as the consequences of government plans, legislation and efforts to combat the backlog. Much of the evidence here is anecdotal, though several individuals and organisations are working towards more concrete and long-term data sets and case studies to support what most of the sector are concerned about: that legal aid for asylum seekers is no longer sustainable.

Those really interested in the topic should take a look at Jo Wilding’s excellent The Legal Aid Market: Challenges for Publicly Funded Immigration and Asylum Legal Representation (2021), which Nick Nason reviewed for us.

What is legal aid?

Legal aid provides fixed fee payments to solicitors, barristers or other qualified advisers in exchange for assisting in cases where the individual would otherwise not have been able to afford help. Refugees often fleeing their homes with nothing but they are faced by a complex, confusing and bureaucratic asylum system administered by a state that often breaks its own laws.

Refugees are eligible to get help with their initial application to the Home Office. This is means tested and help can only be provided at this stage if the case is not “clearly hopeless” or would amount to an abuse of process. If the asylum application is refused by the Home Office, the asylum seeker can help with their appeal. Again, this is means tested. At the appeals stage, legal aid can only be provided if the lawyer assesses that there is at least a 50% chance of success. Lawyers are monitored for their success rate.

The amount of time that can be spent on a legal aid case is usually limited because the amount paid to the lawyer is a fixed fee. Put bluntly, if the lawyer spends too long on too many cases their income will not change and they will not be able to afford to pay their overheads and salaries. They will go bust.

There are also a number of things that would ideally be done, such as attending an asylum interview, that legal aid funding does not necessarily cover. Under section 25 of the Nationality and Borders Act, individuals who are served with a Priority Removal Notice by the Home Office are only eligible for up to seven hours of free legal advice. This is very limiting.

It is one thing to be eligible for legal aid. It is another whether you can actually access it in real life.

Can asylum seekers still get legal aid?

In the year ending September 2022, there were 72,027 asylum applications. In the year ending August 2022, there were a total of 32,714 legal aid cases opened in England and Wales. These dates don’t match up exactly due to a disparity in the data collection periods. If you take out some people also being accommodated in Scotland, and in Northern Ireland (where the provisions are different), then you are left with a total of at least 25,000 asylum seekers that have entered the UK in the past year that have not been able to access legal aid. This is roughly 50% of all asylum seekers that remain in England and Wales.

If the lack of proper access initial legal aid wasn’t bad enough, a number of legal aid contractors have made decisions to stop providing all or certain sections of legal aid support because it is no longer sustainable. There are thought to be a number of firms unable or unwilling to do any work towards evidence gathering for first asylum claims. Often, the only assistance provided is to help with the initial paperwork and then the client is just told to wait for an interview. That is hand-holding, not legal help in any meaningful sense. And one of the largest legal aid contractors in the UK is reported to have completely stopped representing asylum seekers at the appeal stage.

If Rishi Sunak’s plan to reduce the asylum backlog to around 20,000 cases by the end of 2023 is to come to fruition, more than 8,000 decisions will need to be made each month next year. The Home Office is recruiting a huge number of new caseworkers to assist with this. But new caseworkers dealing with complex asylum claims are more likely to make incorrect decisions more often. The consequence may be a greater number of cases going to appeal than we are currently seeing.

Where appeals are necessary, the government’s announcement that they are increasing funding to the tribunals in an attempt to clear around 9,000 cases by March 2023 will not help access to justice. When asked about whether the reduction in the number of legal aid providers assisting with appeals has or will trigger the consideration of a need for any action by the Legal Aid Agency, they claimed they “are not concerned about gaps emerging”.

Miscarriages of justice are more likely in appeal cases, where increasingly fewer legal aid lawyers are available and the courts are being pressured into clearing cases quickly. Assessing the success of the asylum system on numerical data (speed and the number of decisions made) risks creating an asylum system that regularly breaches human rights and access to justice. These big decisions cannot be made without a parallel assessment of legal aid.

Systematic underfunding

This would all be bad enough, but it comes on top of years of systematic underfunding, leading to fewer and fewer providers of immigration legal aid. Those that still exist have had to decrease their capacity and increase the number of private clients they take on to stay afloat.

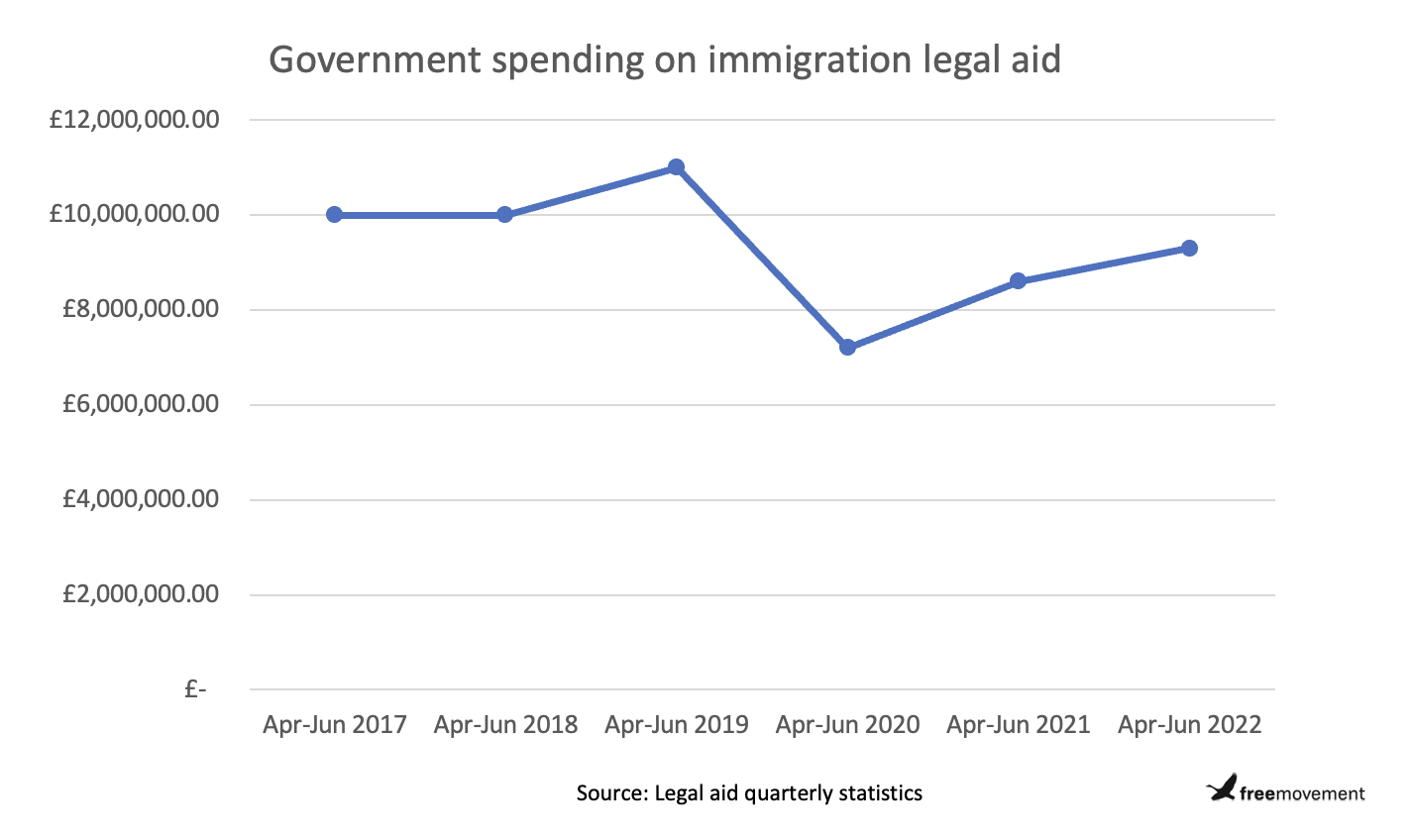

Taking a general look at funding for legal aid, the chart below shows that legal aid expenditure is not yet back at the level it was before the pandemic. Expenditure by the Legal Aid Agency has increased a little recently, and some improvements to the rates in certain areas have been published in the government’s response to the immigration legal aid fees consultation. But the increase does not factor in the cost of living and inflation and does not cover all areas.

Legal aid is clearly in crisis. Whilst it is the Ministry of Justice not the Legal Aid Agency that controls the rates, the fact that the Legal Aid Agency doesn’t do anything to monitor the capacity and demand in the market is worrying.

Funding is a huge deciding factor when legal aid lawyers and firms are considering whether they can take on new legal aid cases, or even remain in the sector long term. As a result, getting access to any kind of legal aid is time-consuming in itself. It may well be a worrying and traumatic process for many, particularly when seeing the new plans for decision-making times that Sunak announced.

A few voluntary organisations working with refugees have started to collect preliminary data on access to lawyers. One has only been able to refer 5% of clients to a lawyer over the last six months.

When asked about legal aid for asylum seekers at a House of Lords Justice and Home Affairs Committee hearing, Home Secretary Suella Braverman said that there is “no shortage of lawyers out there advising individuals on action they can take against the Home Office”, as evidenced by the number of judicial reviews the Home Office receives every year. But judicial reviews are different. The work is different and the fees are substantially higher than the fees for asylum application and appeal cases. Often this is because it is possible to recover costs from the Home Office where their decision-making has been poor.

While there are public law lawyers willing to take on judicial review challenges, very few asylum legal aid lawyers are left. Combine this with the new plans to expedite decision-making over 2023, and the number of brand new caseworkers making these decisions, which means that poor decisions may be even more common, the Home Office should be prepared to dish out much more money in the long run on judicial reviews and appeals, than they would on legal aid lawyers assisting in the initial asylum cases.

Not all lawyers are good lawyers

When asylum seekers are unable to find good legal aid solicitors, they can fall prey to exploitative or simply just bad advisers. A lack of good legal representation means a lack of access to justice. And without good legal representation, many asylum seekers will almost definitely have negative decisions on their asylum claims.

The Office of the Immigration Services Commissioner has worked to improve the level of regulated immigration advisers and improve the quality of advice and general firm work. However, there are still some significant gaps, such as 52% of organisations monitored by the commission confirming that they had no training budget. This is worrying, with an ever-changing system and new new, new, immigration plans being released almost quarterly.

At the end of last year, the government published its response to the immigration legal aid fees consultation. Providers will now be able to conduct age assessment appeals, which will now be heard in the First-Tier Tribunal. As a reflection of the fact that some providers may not have appropriate experience in this work, the government is considering what training could be offered, including a potential accreditation process. But without funding in place, this is something that many providers may not be able to participate in.

A lack of proper representation for asylum seekers comes at a cost. Asylum seekers bear most of the negative impact but the Home Office also inevitably pays the price. People often arrive at legal aid firms after they have been in the UK for years, having paid thousands to poor-quality solicitors, or represented themselves. The ‘fix’ is subsequently made under legal aid. The costs here are more for the government compared to finding the original asylum claim because of the amount of work that is then required.

Legal aid deserts

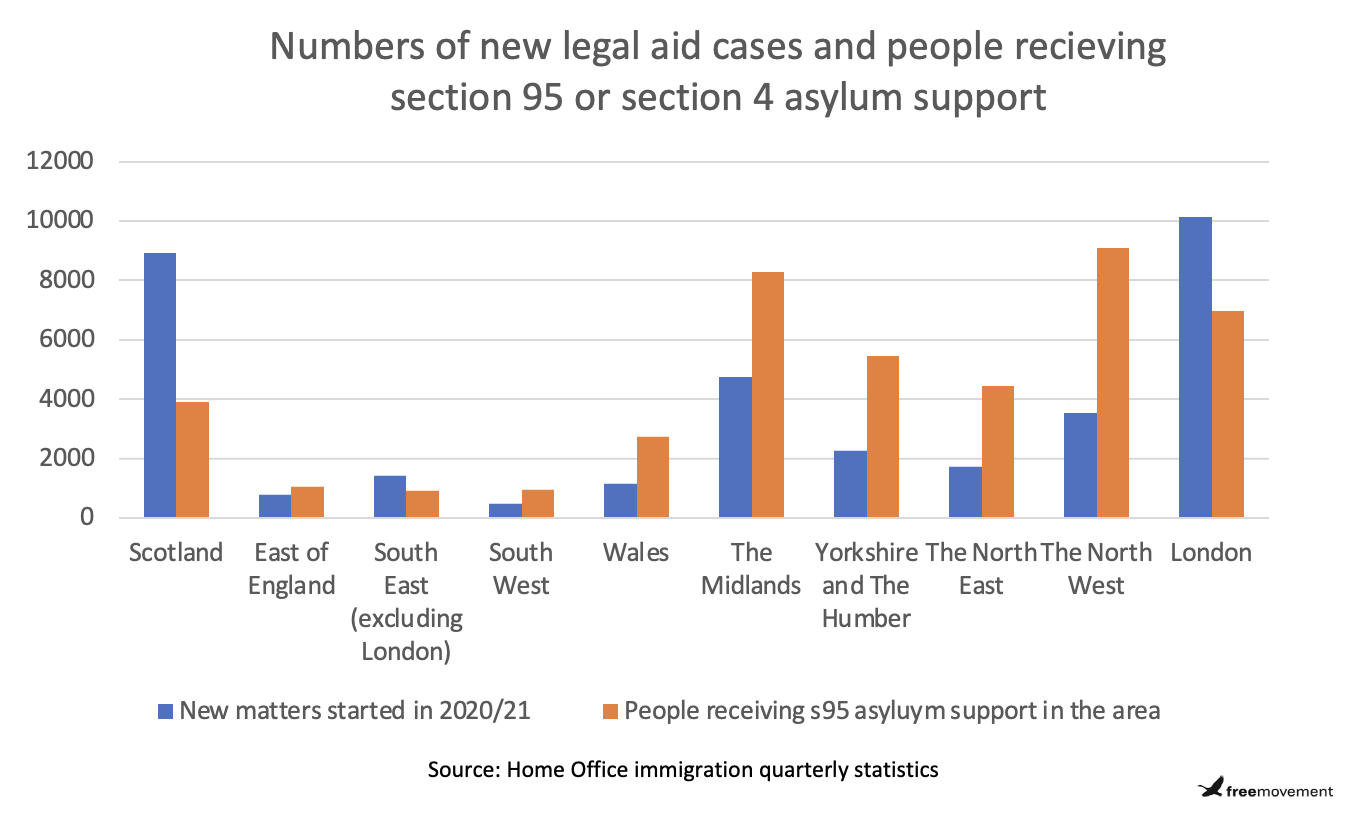

Some areas of the UK fare worse than others if you look at whether and where access to support is available. The Ministry of Justice suggests that it is misleading to compare legal aid services by local authority area because larger procurement areas are used covering multiple local authorities. But taking a more broad look in the table below, it is clear that the number of legal aid cases taken on compared to the number of people receiving section 95 asylum support (as an example) is worryingly incomparable in several locations where asylum seekers are currently often being housed.

Reports suggest that many of the people that have been moved out of the overcrowded processing centre in Manston were transferred to hotels in Norwich. Yet there is no legal advice centre in the entire country of Norfolk. Nor in Suffolk. Or Essex. The closest legal aid provision is in Luton, over one hundred miles away, making legal aid inaccessible to many.

Conclusion

Asylum seekers come to the UK having already faced persecution and trauma. They should have access to justice when they get here, which requires access to good quality legal representation. Everyone should be given a fair chance to fight their case.

But almost half of asylum seekers are unable to access legal aid assistance. An increasing number of firms are unable to tolerate the financial losses of doing appeal work. The is the context in which the government plans to increase exponentially the rate of asylum decisions throughout 2023. Without significant changes, there simply will not be any lawyers available to take on all these cases.